John McDonnell has graciously shared with readers of the Victorian Web his website with the electronic text, including scanned images, of the anonymous London Characters and the Humourous Side of London Life. With Upwards of 70 Illustrations apparently by a "Mr. Jones," which the London firm Stanley Rivers & Co. published in 1871. Brackets indicate explanatory material, such as interpretations of contemporary slang, by Mr. McDonnell. — George P. Landow.]

here is a passage in old Pepys's Diary, written two centuries and odd ago, which, thanks to the permanence of our English

institutions, would do very well for the present day: "Walked into St. James's Park and there found great and very noble

alternations . . . 1662, July 27, I went to walk in the Park, which is now every day more and more pleasant by the new works

upon it." Such eulogistic language is justly due to Mr. Layard and his immediate predecessor at the Board of Works. Suppose

that I live at Bayswater, and my business takes me down to Westminster every day, it is certainly best for me that, instead of

taking 'bus, or cab, or underground railway, I should, like honest Pepys, saunter in the Park and admire the many "noble

alterations." I venture to call poor Pepys honest because he is so truthful; but never thinking that his cipher would be

discovered he has mentioned in his Diary so many unprintable things, that I am afraid we must use that qualifying phrase

"indifferently honest." Several gentlemen who live at Bayswater and practise at Westminster may find that the phrase suits

well, and a man's moral being may be all the better, as through lawns and alleys and copses, where each separate step almost

brings out a separate vignette of beauty, he traverses in a north-westerly direction the whole length of our Parks.

here is a passage in old Pepys's Diary, written two centuries and odd ago, which, thanks to the permanence of our English

institutions, would do very well for the present day: "Walked into St. James's Park and there found great and very noble

alternations . . . 1662, July 27, I went to walk in the Park, which is now every day more and more pleasant by the new works

upon it." Such eulogistic language is justly due to Mr. Layard and his immediate predecessor at the Board of Works. Suppose

that I live at Bayswater, and my business takes me down to Westminster every day, it is certainly best for me that, instead of

taking 'bus, or cab, or underground railway, I should, like honest Pepys, saunter in the Park and admire the many "noble

alterations." I venture to call poor Pepys honest because he is so truthful; but never thinking that his cipher would be

discovered he has mentioned in his Diary so many unprintable things, that I am afraid we must use that qualifying phrase

"indifferently honest." Several gentlemen who live at Bayswater and practise at Westminster may find that the phrase suits

well, and a man's moral being may be all the better, as through lawns and alleys and copses, where each separate step almost

brings out a separate vignette of beauty, he traverses in a north-westerly direction the whole length of our Parks.

He turns aside into St. James's Park, and then goes through the Green Park and crosses Piccadilly to lounge through Hyde Park, and so home through Kensington Gardens. The alterations this season in Hyde Park are very noticeable. All the Park spaces recently laid out have been planned in a style of beauty in harmony with what previously existed; a beauty, I think, unapproachable by the many gardens of Paris, or the Prado of Madrid, the Corso of Rome, the Strado di Toledo of Naples, the Glacis of Vienna. The most striking alterations are those of the Park side near the Brompton road, where the low, bare, uneven ground, as if by magic touch of a transformation, is become exquisite garden spaces with soft undulations, set with starry gems of the most exquisite flowers, bordered by freshest turf. The palings which the mob threw down have been all nobly replaced, and more and more restoration is promised by a Government eager to be popular with all classes. Most of all, the mimic ocean of the Serpentine is to be renewed; and when its bottom is levelled, its depth diminished, and the purity of the water secured, we shall arrive at an almost ideal perfection.

As we take our lounge in the afternoon it is necessary to put on quite a different mental mood as we pass from one Park to

another. We pass at once from turmoil into comparative repose as we enter the guarded enclosure encircled on all sides by a

wilderness of brick and mortar. You feel quite at ease in that vast palatial garden of St. James. Your office coat may serve in St.

James's, but your adorn yourself with all adornments for Hyde Park. You go leisurely along, having adjusted your watch by

the Horse Guards, looking at the soldiers, and the nurses, and the children, glancing at the island, and looking at the

ducks -- the dainty, overfed ducks -- suggesting all sorts of ornithological lore, not to mention low materialistic associations of

green peas or sage and onions. Those dissipated London ducks lay their heads under their wings and go to roost at quite

fashionable hours, that would astonish their primitive country brethren. I hope you like to feed ducks, my friends. All great,

good-natured people have a "sneaking kindness" for feeding ducks. There is a most learned and sagacious bishop who won't

often show himself to human bipeds, but he may be observed by them in his grounds feeding ducks while philosophising on

things in general, and the University Tests in particular. Then what crowded reminiscences we might have of St. James's Park

and of the Mall -- of sovereigns and ministers, couriers and fops, lords and ladies, philosophers and thinkers! By this sheet of

water, or rather by the pond that then was a favorite resort for intending suicides, Charles II would play with his dogs or

dawdle with his mistresses; feeding the ducks here one memorable morning when the stupendous revelation of a Popish plot

was made to his incredulous ears; or looking grimly towards the Banqueting Hall where his father perished, when the debate

on the Exclusion Bill was running fiercely high. But the reminiscences are endless which belong to St. James's Park. Only a

few years ago there was the private entrance which Judge Jeffreys used to have by special licence into the Park, but now it has

been done away. There were all kinds of superstitions floating about in the uninformed Westminster mind about Judge

Jeffreys. What Sydney Smith said in joke to the poaching lad, "that he had a private gallows," was believed by the

Westmonasterians to be real earnest about Jeffreys -- that he used after dinner to seize hold of any individual to whom he

might take a fancy and hang him up in front of his house for his own personal delectation. I am now reconciled to the bridge

that is thrown midway across, although it certainly limits the expanse of the ornamental water. But standing on the

ornamental bridge, and looking both westward and eastward, I know of hardly anything comparable to that view. That green

neat lawn and noble timber, and beyond the dense foliage the grey towers of the Abbey, and the gold of those Houses of

Parliament, which, despite captious criticism, will always be regarded as the most splendid examples of the architecture of the

great Victorian era, and close at hand the paths and the parterres, cause the majesty and greatness of England to blend with this

beautiful oasis islanded between the deserts of Westminster and Pimlico. Looking westward, too, towards Buckingham

Palace -- the palace, despite exaggerated hostile criticism, is at least exquisitely proportioned; but then one is sorry to hear about

the Palace that the soldiers are so ill stowed away there; and the Queen does not like it; and the Hanoverian animal pecularly

abounds. We recollect that once when her Majesty was ill, a servant ran out of the palace to charter a cab and go for the doctor,

because those responsible for the household had not made better arrangements. In enumerating the Parks of London, we

ought not to forget the Queen's private garden of Buckingham Palace, hardly less than the Green Park in extent, and so

belonging to the system of the lungs of London.

As we take our lounge in the afternoon it is necessary to put on quite a different mental mood as we pass from one Park to

another. We pass at once from turmoil into comparative repose as we enter the guarded enclosure encircled on all sides by a

wilderness of brick and mortar. You feel quite at ease in that vast palatial garden of St. James. Your office coat may serve in St.

James's, but your adorn yourself with all adornments for Hyde Park. You go leisurely along, having adjusted your watch by

the Horse Guards, looking at the soldiers, and the nurses, and the children, glancing at the island, and looking at the

ducks -- the dainty, overfed ducks -- suggesting all sorts of ornithological lore, not to mention low materialistic associations of

green peas or sage and onions. Those dissipated London ducks lay their heads under their wings and go to roost at quite

fashionable hours, that would astonish their primitive country brethren. I hope you like to feed ducks, my friends. All great,

good-natured people have a "sneaking kindness" for feeding ducks. There is a most learned and sagacious bishop who won't

often show himself to human bipeds, but he may be observed by them in his grounds feeding ducks while philosophising on

things in general, and the University Tests in particular. Then what crowded reminiscences we might have of St. James's Park

and of the Mall -- of sovereigns and ministers, couriers and fops, lords and ladies, philosophers and thinkers! By this sheet of

water, or rather by the pond that then was a favorite resort for intending suicides, Charles II would play with his dogs or

dawdle with his mistresses; feeding the ducks here one memorable morning when the stupendous revelation of a Popish plot

was made to his incredulous ears; or looking grimly towards the Banqueting Hall where his father perished, when the debate

on the Exclusion Bill was running fiercely high. But the reminiscences are endless which belong to St. James's Park. Only a

few years ago there was the private entrance which Judge Jeffreys used to have by special licence into the Park, but now it has

been done away. There were all kinds of superstitions floating about in the uninformed Westminster mind about Judge

Jeffreys. What Sydney Smith said in joke to the poaching lad, "that he had a private gallows," was believed by the

Westmonasterians to be real earnest about Jeffreys -- that he used after dinner to seize hold of any individual to whom he

might take a fancy and hang him up in front of his house for his own personal delectation. I am now reconciled to the bridge

that is thrown midway across, although it certainly limits the expanse of the ornamental water. But standing on the

ornamental bridge, and looking both westward and eastward, I know of hardly anything comparable to that view. That green

neat lawn and noble timber, and beyond the dense foliage the grey towers of the Abbey, and the gold of those Houses of

Parliament, which, despite captious criticism, will always be regarded as the most splendid examples of the architecture of the

great Victorian era, and close at hand the paths and the parterres, cause the majesty and greatness of England to blend with this

beautiful oasis islanded between the deserts of Westminster and Pimlico. Looking westward, too, towards Buckingham

Palace -- the palace, despite exaggerated hostile criticism, is at least exquisitely proportioned; but then one is sorry to hear about

the Palace that the soldiers are so ill stowed away there; and the Queen does not like it; and the Hanoverian animal pecularly

abounds. We recollect that once when her Majesty was ill, a servant ran out of the palace to charter a cab and go for the doctor,

because those responsible for the household had not made better arrangements. In enumerating the Parks of London, we

ought not to forget the Queen's private garden of Buckingham Palace, hardly less than the Green Park in extent, and so

belonging to the system of the lungs of London.

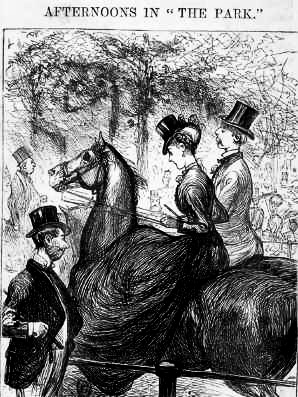

But we now enter the great Hyde Park itself, assuredly the most brilliant spectacle of the kind which the world can show. It is a scene which may well tax all your powers of reasoning and of philosophy. And you must know the Park very well, this large open drawing-room which in the season London daily holds, before you can sufficiently temper your senses to be critical and analytical -- before you can eliminate the lower world, the would-be fashionable element, from the most affluent and highest kind of metropolitan life -- before you can judge of the splendid mounts and the splendid comparisons, between fine carriages and fine horses -- fine carriages where perhaps the cattle are lean and poor, or fine horses where the carriages are old and worn; the carriages and horses absolutely gorgeous, but with too great a display; and, again, where the perfection is absolute, but with as much quietude as possible, the style that chiefly invites admiration by the apparent desire to elude it. In St. James's Park you may lounge and be listless if you like; but in Hyde Park, though you may lounge, you must still be alert. Very pleasant is the lounge to the outer man, but in the inner mind you must be observant, prepared to enjoy either the solitude of the crowd, or to catch the quick glance, the silvery music of momentary merriment, then have a few seconds of rapid, acute dialogue, or perhaps be beckoned into a carriage by a friend with space to spare. As you lean over the railings you perhaps catch a sight of a most exquisite face -- a face that is photographed on the memory for its features and expression. If you have really noticed such a face the day is a whiter day to you; somehow or other you have made an advance. But it is mortifying, when you contemplate this beautiful image, to see some gilded youth advance, soulless, brainless, to touch the fingers dear to yourself and look into eyes which he cannot fathom or comprehend. Still more annoying to think that a game is going on in the matrimonial money market. I sometimes think that the Ladies' Mile is a veritable female Tattersall's, where feminine charms are on view and the price may be appraised -- the infinite gambols and curvettings of high-spirited maidenhood. But I declare on my conscience that I believe the Girl of the Period has a heart, and that the Girl of the Period is not so much to blame as her mamma or her chaperone.

But, speaking of alterations, I cannot say that all the alterations are exactly to my mind. It is not at all pleasing that the habit of smoking has crept into Rotten Row. The excuse is that the Prince smokes. But because one person of an exceptional and unique position, doubtless under exceptional circumstances, smokes, that is no reason why the mass should follow the example. Things have indeed changed within the last few years; the race is degenerating into politeness. In the best of his stories, "My Novel," Lord Lytton makes Harley, his hero, jeer at English liberty; and he says: "I no more dare smoke this cigar in the Park at half-past six, when all the world is abroad, than I dare pick my Lord Chancellor's pocket, or hit the Archbishop of Canterbury a thump on the nose." Lord Hatherley's pocket is still safe, and we are not yet come to days, though we seem to be nearing them, when a man in a crowd may send a blow into a prelate's face. We have had such days before, and we may have them again. But smoking is now common enough, and ought to be abated as a nuisance. Some ladies like it, and really like it; and that is all very well, but other ladies are exceedingly annoyed. A lady takes her chair to watch the moving panorama, intending perhaps to make a call presently, and men are smoking within a few paces to her infinite annoyance and the spoiling of her pleasure. Her dress is really spoilt, and there is the trouble of another toilet. Talking of toilets, I heard a calculation the other day of how many the Princess of Wales had made in a single day. She had gone to the laying of the foundation stone of Earlswood asylum, and then to the great State breakfast at Buckingham Palace, and then a dinner and a ball, and one or two other things. The Princess truly works very hard, harder indeed than people really know. I went the other day to a concert, where many a one was asked to go, and the Princess was there, in her desire to oblige worthy people, and sat it all through to the very last with the pleasantest smiles and the most intelligent attention. Let me also, since I am criticizing, say that the new restaurant in the Park is a decided innovation, and that to complete the new ride, to carry Rotten Row all round the Park, is certainly to interfere with the enjoyment of pedestrians. It is, however, to be said, in justice, that the pedestrians have the other parks pretty much to themselves. There is, however, a worse error still, in the rapid increase of the demi-monde [class of women of doubtful reputation] in the Park. A man hardly feels easy in conducting a lady into the Park and answering all the questions that may be put to him respecting the inmates of gorgeous carriages that sweep by. These demireps [women of suspected chastity] make peremptory conditions that they shall have broughams for the Park and tickets for the Horticultural, and even for the fetes at the Botanical Gardens. This is a nuisance that requires to be abated as much as any in Regent Street or the Haymarket. The police ought to have peremptory orders to exclude such carriages and their occupants. Twenty years ago there was a dead set made in Cheshire, against the aspirants of Liverpool and Manchester, by the gentry of that county most famous for the pedigree of the gentry, who wished to maintain the splendour of family pride. For instance, the steward of a county ball went up to a manufacturer who was making his eighty thousand a year, and told him that no tradesman was admitted. That was of course absurd; but still, if that was actually done, an inspector should step up to the most fashionable Mabel or Lais, and turn her horses' heads, if obstreperous, in the direction of Bridewell or Bow Street. Anonyma has ruled the Park too much. The favourite drive used to be round the Serpentine; but when the prettiest equipage in London drew all gazers to the Ladies' Mile, the Serpentine became comparatively unused, and the Ladies' Mile, ground infinitely inferior, became the favourite until the renovated Serpentine or change of whim shall mould anew the fickle, volatile shape of fashionable vagary.

At this present time Mr. Alfred Austin's clever satire "The Season" -- a third edition of which is published -- occurs to me. The poem is a very clever one, and it is even better appreciated on the other side of the Channel than on this, as is evidenced by M. Forques' article on the subject in the "Revue des Deux Mondes." We will group together a few passages from Mr. Austin's vigorous poem, belonging to the Parks.

"I sing the Season, Muse! whose sway extends

Where Hyde begins, beyond where Tyburn ends;

Gone the broad glare, save where with borrowed bays

Some female Phaeton sets the drive ablaze.

Dear pretty fledglings! come from country nest,

To nibble, chirp, and flutter in the west;

Whose clear, fresh faces, with their fickle frown

And favour, start like Spring upon the town;

Less dear, for damaged damsels, doomed to wait;

Whose third -- fourth? season makes half desperate,

Waking with warmth, less potent hour by hour

(As magnets heated lose attractive power).

Or you, nor dear nor damsels, tough and tart,

Unmarketable maidens of the mart,

Who, plumpness gone, fine delicacy feint,

And hide your sin in piety and paint.

"Incongruous group, they come; the judge's hack,

With knees as broken as its rider's back;

The counsel's courser, stumbling through the throng,

With wind e'en shorter than its lord's is long;

The foreign marquis's accomplished colt

Sharing its owner's tendency to bolt.

"Come let us back, and whilst the Park's alive,

Lean o'er the railings, and inspect the Drive.

Still sweeps the long procession, whose array

Gives to the lounger's gaze, as wanes the day,

Its rich reclining and reposeful forms,

Still as bright sunsets after mists or storms;

Who sit and smile (their morning wrangling o'er,

Or dragged and dawdled through one dull day more),

As though the life of widow, wife and girl,

Were one long lapsing and voluptuous whirl.

O, poor pretence! what eyes so blind but see

The sad, however elegant ennui?

Think you that blazoned panel, prancing pair,

Befool our vision to the weight they bear?

The softest ribbon, pink-lined parasol,

Screen not the woman, though they deck the doll.

The padded corsage and the well-matched hair,

Judicious jupon spreading out the spare,

Sleeves well designed false plumpness to impart,

Leave vacant still the hollows of the heart.

Is not our Lesbia lovely? In her soul

Lesbia is troubled: Lesbia hath a mole;

And all the splendours of that matchless neck

Console not Lesbia for its single speck.

Kate comes from Paris, and a wardrobe brings,

To which poor Edith's are 'such common things;'

Her pet lace shawl has grown not fit to wear,

And ruined Edith dresses in despair."

Mr. Austin is sufficiently severe upon the ladies, especially those whose afternoons in the Park have some correspondence with their "afternoon of life." I think that the elderly men who affect youthful airs are every whit as numerous and as open to sarcasm. Your ancient buck is always a fair butt. And who does not know these would-be juveniles, their thin, wasp-like waists, their elongated necks and suspensory eye-glasses, their elaborate and manufactured hair? They like the dissipations of youth so well that they can conceive of nothing more glorious, entirely ignoring that autumnal fruit is, after all, better than the blossom or foliage of spring or early autumn. All they know indeed of autumn is the variegation and motley of colour. The antiquated juvenile is certainly one of the veriest subjects for satire; and antiquated juveniles do abound of an afternoon in Rotten Row. Nothing we can say about a woman's padding can be worse than the padding which is theirs. All their idiotic grinning cannot hide the hated crows'-feet about their goggle, idiotic eyes. They try, indeed, the power of dress to the utmost; but in a day when all classes are alike extravagant in dress, even the falsity of the first impression will not save them from minute criticism. Talk to them and they will draw largely on the reminiscences of their youth, perhaps still more largely on their faculty of invention. What a happy dispensation it is in the case of men intensely wicked and worldly, that in youth, when they might do infinite evil, they have not the necessary knowledge of the world and of human nature to enable them to do so; and when they have a store of wicked experience, the powers have fled which would have enabled them to turn it to full account! At this moment I remember a hoary old villain talking ribaldry with his middle-aged son, both of them dressed to an inch of their lives, and believing that the fashion of this world necessarily endures forever. Granting the tyranny and perpetuity of fashion -- for in the worst times of the French revolution fashion still maintained its sway, and the operas and theatres were never closed -- still each individual tyrant of fashion has only his day, and often the day is a very brief one. Nothing is more becoming than gray hairs worn gallantly and well, and when accompanied with sense and worth they have often borne away a lovely bride, rich and accomplished, too, from some silly, gilded youth. I have known marriages between January and May, where May has been really very fond of January. After all, the aged Adonis generally pairs off with some antiquated Venus; the juvenilities on each side are eliminated as being common to both and of no real import, and the settlement is arranged by the lawyers and by family friends on a sound commercial basis.

It is very easy for those who devote themselves to the study of satirical composition, and cultivate a sneer for things in general, to be witty on the frivolities of the Park. And this is the worst of satire, that it is bound to be pungent, and cannot pause to be discriminating and just. Even the most sombre religionist begins to understand that he may use the world, without trying to drain its sparkling cup to the dregs. Hyde Park is certainly not abandoned to idlesse. The most practical men recognise its importance and utility to them. There are good wives who go down to the clubs or the Houses in their carriages to insist that their lords shall take a drive before they dine and go back to the House. And when you see saddle-horses led up and down in Palace Yard, the rider will most probably take a gallop before he comes back to be squeezed and heated by the House of Commons, or be blown away by the over-ventilation of the House of Lords. A man begins to understand that it is part of his regular vocation in life to move about in the Park. And all men do so, especially when the sun's beams are tempered and when the cooling evening breeze is springing up. The merchant from the City, the lawyer from his office, the clergyman from his parish, the governess in her spare hours, the artist in his love of nature and human nature, all feel that the fresh air and the fresh faces will do them good. There was a literary man who took a Brompton apartment with the back windows fronting the Park. Hither he used to resort, giving way to the fascination which led him, hour after hour, to study the appearances presented to him. The subject is, indeed, very interesting and attractive, including especially the very popular study of flirtation in all its forms and branches. If you really want to see the Row you must go very early in the afternoon. Early in the afternoon the equestrians ride for exercise; later they ride much in the same way as they promenade. The Prince, for a long time, used to ride early in the afternoon, if only to save himself the trouble of that incessant salutation which must be a serious drawback on H. R. H.'s enjoyment of his leisure. Or, again, late in the evening, it is interesting to note the gradual thinning of the Park and its new occupants come upon the scene. The habitue of Rotten Row is able, with nice gradations, to point out how the cold winds and rains of the early summer have, night after night, emptied the Park at an earlier hour, or how a fete at the Horticultural, or a gala at the Crystal Palace, has sensibly thinned the attendance. As the affluent go home to dress and dine, the sons and daughters of penury who have shunned the broad sunlight creep out into the vacant spaces. The last carriages of those who are going home from the promenade meet the first carriages of those who are going out to dine. Only two nights ago I met the carriage of Mr. Disraeli and his wife. I promise you the Viscountess Beaconsfield looked magnificent. Curiously enough, they were dining at the same house where, not many years ago, Mr. Disraeli dined with poor George Hudson. When Mr. Hudson had a dinner given to him lately, it is said that he was much affected, and told his hosts that its cost would have kept him and his for a month.

The overwhelming importance of the Parks in London is well brought out by that shrewd observer, Crabb Robinson, in his Diary. Under February 15, 1818, he writes: "At two I took a ride into the Regent's Park, which I had never seen before. When the trees are grown this will be really an ornament to the capital; and not a mere ornament, but a healthful appendage. The Highgate and Hampstead Hill is a beautiful object; and within the Park the artificial water, the circular belt or coppice, the few scattered bridges, &c., are objects of taste. I really think this enclosure, with the new street leading to it from Carlton House (Regent Street) will give a sort of glory to the Regent's government, greater than the victories of Trafalgar and Waterloo, glorious as these are." Here again, almost at haphazard, is a quotation from an American writer: "So vast is the extent of these successive ranges, and so much of England can one find, as it were, in the midst of London. Oh, wise and prudent John Bull, to enoble thy metropolis with such spacious country walks, and to sweeten it so much with coutry air! Truly these lungs of London are vital to such a Babylon, and there is no beauty to be compared to them in any city I have ever seen. I do not think the English are half proud enough of their capital, conceited as they are about so many things besides. Here you see the best of horse-flesh, laden with the 'porcelain clay' of human flesh. Ah! how daringly the ladies go by, and how ambitiously their favoured companions display their good fortune in attending them. Here a gay creature rides independently enough with her footman at a respectful distance. She is an heiress, and the young gallants she scarce deigns to notice are dying for love of her and her guineas."

But, after all, is there anything more enjoyable in its way than Kensington Gardens? You are not so negligé as in St. James's, but it is comparative undress compared with Hyde Park. Truly there are days -- and even in the height of the season too -- when you may lie down on the grass and gaze into the depth of the sky, listening to the murmurous breeze, and that far-off hum which might be a sound of distant waves, and fancy yourself in Ravenna's immemorial wood. Ah, what thrilling scenes have come off beneath these horse-chestnuts with their thick leaves and pyramidal blossoms! And if only those whispers were audible, if only those tell-tale leaves might murmur their confessions, what narratives might these supply of the idyllic side of London life, sufficient to content a legion of romancists! It is a fine thing for Orlando to have a gallop by the side of his pretty ladylove down the Row, but Orlando knows very well that if he could only draw her arm through his and lead her down some vista in those gardens, it would be well for him. Oh, yielding hands and eyes! oh, mantling blushes and eloquent tears! oh, soft glances and all fine tremor of speech, in those gardens more than in Armina's own are ye abounding. There is an intense human interest about Kensington Gardens which grows more and more, as one takes one's walks abroad and the scene becomes intelligible. See that slim maid demurely reading beneath yonder trees, those old trees which artists love in the morning to come and sketch. She glances more than once at her watch, and then suddenly with surprise she greets a lounger. I thought at the very first that her surprise was an affection; and as I see how she disappears with him through that overarching leafy arcade my surmise becomes conviction. As for the nursery maids who let their little charges loiter or riot about, or even sedater governesses with their more serious aims, who will let gentlemanly little boys and girls grow very conversational, while they are very conversational themselves with tall whiskered cousins or casual acquaintance, why, I can only say, that for the sake of the most maternal hearts beating in this great metropolis, I am truly rejoiced to think that there are no carriage roads through the Gardens, and the little ones can hardly come to any very serious mischief.

Are you now inclined, my friends, for a little -- and I promise you it shall really be a little -- discourse concerning those Parks, that shall have a slight dash of literature and history about it? First of all, let me tell you that in a park you ought always to feel loyal, since for our Parks we are indebted to our kings. The very definition of a park is -- I assure you I am quoting the great Blackstone himself -- "an enclosed chase, extending only over a man's own grounds," and the Parks have been the grounds of the sovereign's own self. It is true of more than one British Caesar: --

"Moreover he hath left you all his walks,

His private arbours and new-planted orchards,

On this side Tibur; he hath left them you

And to your heirs for ever; common pleasures

To walk abroad and recreate yourselves."

Once in the far distant time they were genuine parks with beasts of chase. We are told that the City corporation hunted the hare at the head of the conduit, where Conduit Street now stands, and killed the fox at the end of St. Giles's. St. James's Park was especially the courtier's park, a very drawing-room of parks. How splendidly over the gorgeous scene floats the royal banner of England, at the foot of Constitution Hill, which has been truly called the most chastely-gorgeous banner in the world! If you look at the dramatists of the Restoration you find frequent notices of the Park, which are totally wanting in the Elizabethan dramatists, when it was only a nursery for deer. Cromwell had shut up Spring Gardens, but Charles II gave us St. James's Park. In the next century the Duke of Buckingham, describing his house, says: "The avenues to this house are along St. James's Park, through rows of goodly elms on one hand and flourishing limes on the other; that for coaches, this for walking, with the Mall lying between them." It was in the Park that the grave Evelyn saw and heard his gracious sovereign "hold a very familiar discourse with Mrs. Nellie, as they called an impudent comedian, she looking out of her garden on a terrace at the top of the wall." Here Pepys saw "above all Mrs. Stuart in this dress, with her hat cocked and a red plume, with her sweet eye, little Roman nose, and excellent taille, the greatest beauty I ever saw, I think, in my life." Or take a play from Etheridge: --

"Enter Sir Fopling Flutter and his equipage.

"Sir Fop. Hey! bid the coachman send home four of his horses and bring the coach to Whitehall; I'll walk over the Park. Madam, the honour of kissing your fair hands is a happiness I missed this afternoon at my lady Townly's.

"Leo. You were very obliging, Sir Fopling, the last time I saw you there.

"Sir Fop. The preference was due to your wit and beauty. Madam, your servant. There never was so sweet an evening.

"Bellinda. It has drawn all the rabble of the town hither.

"Sir Fop. 'Tis pity there is not an order made that none but the beau monde [fashionable society] should walk here."

In Swift's "Journal to Stella" we have much mentioning of the Park: "to bring himself down," he says, that being the Banting [weight reduction] system of that day, he used to start on his walk about sunset. Horace Walpole says: "My lady Coventry and niece Waldegrave have been mobbed in the Park. I am sorry the people of England take all their liberty out in insulting pretty women." He elsewhere tells us with what state he and the ladies went. "We sailed up the Mall with all our colours flying." We do not hear much of the Green Park. It was for a long time most likely a village green, where the citizens would enjoy rough games, and in the early morning duellists would resort hither to heal their wounded honour.

Originally, Kensington Gardens and Hyde Park were all one. Addison speaks of it in the "Spectator," and it is only since the time of George II that a severance has been made. Hyde Park has its own place in literature and in history. There was a certain first of May when both Pepys and Evelyn were interested in Hyde Park. Pepys says: "I went to Hyde Park to take the air, where was his Majesty and an innumerable appearance of gallants and rich coaches, being now a time of universal festivity and joy." It was always a great place for reviews. They are held there still, and the Volunteers have often given great liveliness to the Park on Saturday. Here Cromwell used to review his terrible Ironsides. It was Queen Caroline who threw a set of ponds into one sheet of water, and as the water-line was not a direct one, it was called the Serpentine. The fosse and low wall was then a new invention; "an attempt deemed so astonishing that the common people called them ha-has to express their surprise at finding a sudden and unperceived check to their walk." It is said that a nobleman who had a house abutting on the Park engraved the words --

"'Tis my delight to be

In the town and the countree."

Antiquaries may find out countless points of interest, and may be able to identify special localities. Once there were chalybeate [impregnated with iron] springs in a sweet glen, now spoilt by the canker of ugly barracks. It was on the cards that the Park might have been adorned with a rotunda instead. Most of the literary associations cluster around Kensington Gardens, concerning which Leigh Hunt has written much pleasant gossip in his "Old Court Suburb." A considerable amount of history and an infinite amount of gossip belong to Kensington Palace, now assigned to the Duchess of Inverness, the morganatic [of lower rank and remaining so] wife of the Duke of Sussex; gossip about George II and his wife, about Lord Hervey, the queen and her maids of honour, the bad beautiful Duchess of Kingston, the charming Sarah Lennox, Selwyn, March, Bubb Doddington, and that crew, whom Mr. Thackeray delighted to reproduce. There is at least one pure scene dear to memory serene, that the Princess Victoria was born and bred here, and at five o'clock one morning was aroused from her slumbers, to come down with dishevelled hair to hear from great nobles that she was now the Queen of the broad empire on which the morning and the evening star ever shines.

I am very fond of lounging through the Park at an hour when it is well-nigh all deserted. I am not, indeed, altogether solitary in my ways and modes. There are certain carriages which roll into the Park almost at the time when all other carriages have left or are leaving. In my solitariness I feel a sympathy with those who desire the coolness and freshness when they are most perfect. I have an interest, too, in the very roughs that lounge about the parks. I think them far superior to the roughs that lounge about the streets. Here is an athletic scamp. I admire his easy litheness and excellent proportion of limb. He is a scamp and a tramp, but then he is such, on an intelligible aesthetical principle. He has flung himself down, in the pure physical enjoyment of life, just as a Neapolitan will bask in the sunshine, to enjoy the turf and the atmosphere. In his splendid animal life he will sleep for hours, unfearing draught or miasma, untroubled with ache or pain, obtaining something of a compensation for his negative troubles and privations. If you come to talk to the vagrant sons and daughters of poverty loitering till the Park is cleared, or even sleeping here the livelong night, you would obtain a clear view of that night side which is never far from the bright side of London. I am not sure that I might not commend such a beat as this to some philanthropist for his special attention. The handsome, wilful boy who has run away from home or school; the thoughtless clerk or shopman out of work; the poor usher, whose little store has been spent in illness; the servant-girl who has been so long without a place, and is now hovering on the borders of penury and the extreme limit of temptation; they are by no means rare, with their easily-yielded secrets, doubtless with some amount of imposture, and always, when the truth comes to be known, with large blame attachable to their faults or weakness, but still with a very large percentage where some sympathy or substantial help will be of the greatest possible assistance. As one knocks about London, one accumulates souvenirs of all kinds -- some, perhaps, that will not very well bear much inspection; and it may be a pleasing reflection that you went to some little expenditure of time or coin to save some lad from the hulks or some girl from ruin.

Last modified 24 November 2012