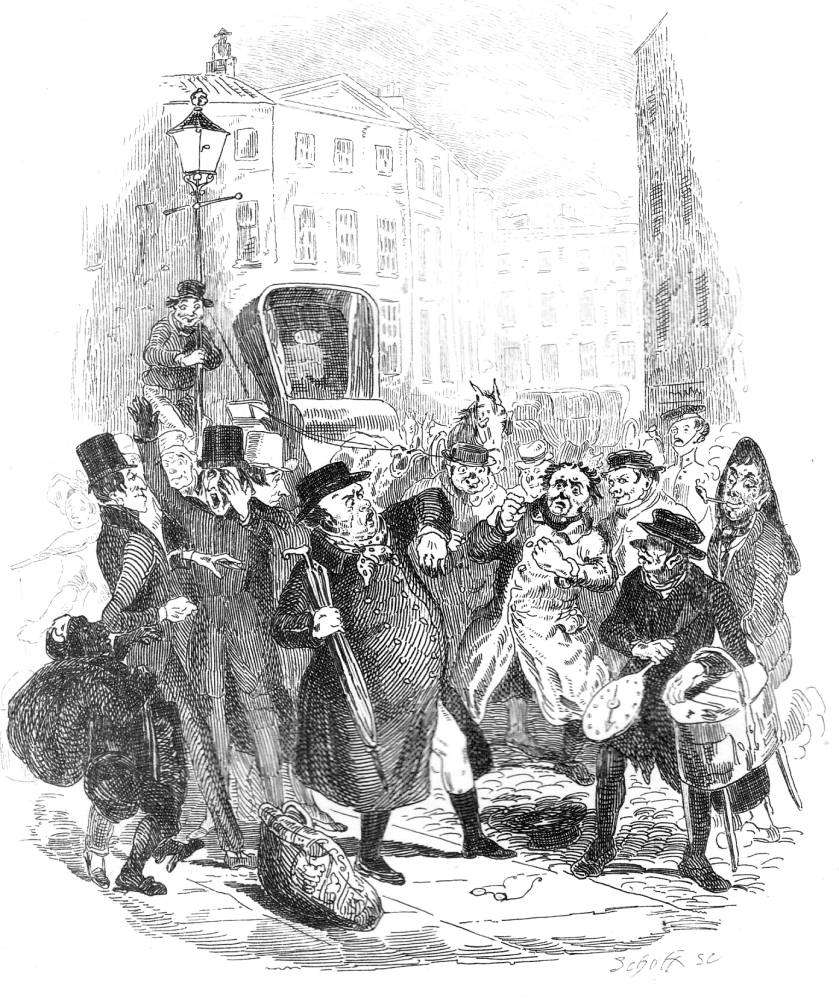

Bump they cums agin the post in Chapter XVII of "Scenes" in Dickens's Sketches by Boz Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-Day People (1877), middle of page 143. Wood-engraving; 4 ⅛ by 5 ⅛ inches (10 cm high by 13 cm wide), framed. The article later entitled "The Last Cab-Driver, and the First Omnibus Cad," originally appeared as one of the first in what would prove Sketches by Boz, Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-Day People (1836, 1839). "The Last Cab-driver, and the First Omnibus Cad" appeared in the periodical Bell's Life in London on 29 November 1835 as "Scenes and Characters No. 6. Some Account of an Omnibus Cad," a conductor named William Barker.

Scanned image, colour correction, sizing, caption, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated: Cabriolet Driving without due Care and Attention

We are not aware of any instance on record in which a cab-horse has performed three consecutive miles without going down once. What of that? It is all excitement. And in these days of derangement of the nervous system and universal lassitude, people are content to pay handsomely for excitement; where can it be procured at a cheaper rate?

But to return to the red cab; it was omnipresent. You had but to walk down Holborn, or Fleet-street, or any of the principal thoroughfares in which there is a great deal of traffic, and judge for yourself. You had hardly turned into the street, when you saw a trunk or two, lying on the ground: an uprooted post, a hat-box, a portmanteau, and a carpet-bag, strewed about in a very picturesque manner: a horse in a cab standing by, looking about him with great unconcern; and a crowd, shouting and screaming with delight, cooling their flushed faces against the glass windows of a chemist’s shop. — "What's the matter here, can you tell me?" — "O'ny a cab, sir." — "Anybody hurt, do you know?" — "O'ny the fare, sir. I see him a turnin’ the corner, and I ses to another gen’lm’n “that's a reg'lar little oss that, and he's a comin' along rayther sweet, an’t he?" — "He just is,” ses the other gen’lm’n, ven bump they cums agin the post, and out flies the fare like bricks." Need we say it was the red cab; or that the gentleman with the straw in his mouth, who emerged so coolly from the chemist's shop and philosophically climbing into the little dickey, started off at full gallop, was the red cab's licensed driver? ["Scenes," Chapter XVII, "The Last Cab Driver and the First Omnibus Cad," p. 134]

Commentary: Of Cabs and Omnibuses

Robert Seymour's The Pugnacious Cabman from Pickwick (1836).

Although George Cruikshank, Dickens's original illustrator for Sketches by Boz, forty years earlier caricatured the peculiar cab driver (an actual London cabbie), both Fred Barnard in the British Household Edition and A. B. Frost in the American edition have offered far more kinetic and realistic responses to Dickens's text. Whereas Cruikshank had provided a static portrait of the driver and his vehicle in a London street, the later illustrators have chosen far more dynamic moments. Whereas Barnard depicts a fight about to break out, Frost depicts the crash in which the unfortunate passenger flies forward out of the cab and the driver is being thrown forward. However, in his manner of depicting the accident without an observer or reporter, Frost creates a dissonance between the textual, first-person account in a Cockney accent (assimilated by the commentator on London life, Boz), and the image. Dickens relates the incident from within the personality of the observer, and then adds dialogue with another person, whereas the illustration moves us much closer to the accident than Dickens's distancing, humorous prose would allow. Frost's illustration, compared to Cruikshank's, is full of energy as he realistically describes the plight of the terrified horse and the overturned carriage. Whereas Dickens's narrator makes the accident seem comical, Frost takes the accident seriously: the horse, driver, and passenger could all be seriously injured, and in the case of the horse if it were to incur grievous injury it would certainly have to be put down. This is one of those cases, like the images of the romantic shipwrecks, where the medium becomes the message to an important extent: the emotional temperature of the image and narrative differ significantly, though in a way opposite that of shipwrecks and other disasters, which often present them from within, whereas the accident in the present image conveys the experience from without. Here Dickens has chosen to take a comical, distanced approach to an event that is no laughing matter because this cab mishap may entail both injury and loss of life.

Commentary: Images for the Chapter in the Household Editions

In the parallel British Household Edition illustration of 1876, Fred Barnard shows an array of bystanders as the little passenger, umbrella under his arm, delivers his complaint about the fare as the cab-driver calmly rolls up his cuffs in preparation for the beating he is about to deliver before eight witnesses at Tottenham Court Road (the sidewalk and buildings sketched in lightly in linear perspective establish the urban setting). However, in the original Cruikshank illustration, despite his providing a realistic urban setting with house- and business-fronts and a street sign, the witnesses in the background are a Cruikshank interpolation as they come from the second half of the sketch. Indeed, Dickens does not allude to there being any witnesses, except, of course, the highly observant "Boz" himself. Although the American Household Edition illustrator A. B Frost had not seen a London cab or omnibus until he visited the city in 1877, he would have recognized what Dickens was describing from the streets of his native New York City — and probably from British periodicals of the period.

In the Frost illustration, Dickens's working-class Cockney witness to accident (who seems much more interested in the well-being of the horse and ubiquitous red cabriolet than in the condition of the passenger) is nowhere in the frame. We may explain the absence of the figure of narrator-observer from the frame if we accept that it is from his perspective that Frost describes the accident; in other words, readers must adopt the eye-witness's perspective, but not his attitude. After bumping up against the hitching post at the corner, the cab-driver has inadvertently caught the spokes of his wheel on the post, thereby tumbling the fare onto the paving-stones; as the driver loses control of the reins, he struggles to remain on the roof. Frost has chosen a far more dramatic moment than George Cruikshank for depiction, taking what was essentially a study of a quirky London character and turning it into a visual account of the accident as it transpires. Dickens's persona, in contrast to the illustrator's concern about the horse and the passenger, ironically dismisses the effect of the accident on both, and focuses on the cause of the mishap, the racing driver's taking the corner too sharply.

Responding to the description rather than the attitude of the observer, Frost does not include the Cockney observer of the accident that befalls the hansom cab, and does not show that other ubiquitous vehicle of the London streets, the multiple-passenger omnibus — a very different, lower-in-class mode of transportation (though not necessarily "lower class") vehicle than the cab. Furthermore, the popular London magazines Punch and Fun, which overseas artists such as Frost and Nast are likely to have seen, were filled with cartoons and illustrations featuring both types of urban transportation. These have to be considered a major aspect of the visual content that these American illustrators would have known.

Pictorial Resources for American Illustrators: London Cabs in Periodicals

- Fun on City Travel — Cabs & Omnibuses

- Seven Views of Onmnibuses in the Victorian Period

- Omnibuses, Coaches, Carriages, and Other Horse-Drawn Vehicles

Artists of the period often depicted hansom cabs in such popular periodicals as Punch and Fun. Such an illustration is John Leech's A Playful Creature, in which the recalcitrant horse rather than the incautious driver is causing the passenger considerable apprehension. Another contemporary visual commentator on hansom cabs in popular periodicals of the 1850s was Dickens's chief illustrator, Phiz (Hablot Knight Browne).

A Selection of Phiz's Interpretations of Hansom Cab Humour

Relevant Illustrations from Other Editions, 1836 through 1876

Left: George Cruikshank's original illustration, The Last Cab-driver, and the First Omnibus Cad (1839). Right: Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s interpretation of the assertive Cockney cabman, The Last Cab-driver. (1867). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Above: Fred Barnard includes a crowd of bystanders sympathetic to neither adversary at Tottenham Court Road in "I may as well get board, lodgin', and washin' till then, out of the country, as pay for it myself; consequently, here goes." (1876).

Bibliography

Ackroyd, Peter. Dickens: A Biography. London: Sinclair-Stevenson, 1990.

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1999.

Dickens, Charles. "Scenes," Chapter 17, "The Last Cab-driver, and the First Omnibus Cad," Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Chapman and Hall, 1839; rpt., 1890. Pp. 104-11.

Dickens, Charles. "Scenes," Chapter 17, "The Last Cab-driver, and the First Omnibus Cad." Christmas Books and Sketches by Boz, Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-day People. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: James R. Osgood, 1875 [rpt. of 1867 Ticknor & Fields edition]. Pp. 305-10.

Dickens, Charles. "Scenes," Chapter 17, "The Last Cab-driver, and the First Omnibus Cad." Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1876. Pp. 66-71 .

Dickens, Charles. "Scenes," Chapter 17, "The Last Cab-driver, and the First Omnibus Cad." Pictures from Italy, Sketches by Boz and American Notes. Illustrated by Thomas Nast and Arthur B. Frost. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1877 (copyrighted in 1876). Pp. 133-136.

Dickens, Charles. "Scenes," Chapter 17, "The Last Cab-driver, and the First Omnibus Cad." Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. I, 133-42.

Dickens, Charles, and Fred Barnard. The Dickens Souvenir Book. London: Chapman & Hall, 1912.

Hawksley, Lucinda Dickens. Chapter 3, "Sketches by Boz." Dickens Bicentenary 1812-2012: Charles Dickens. San Rafael, California: Insight, 2011. Pp. 12-15.

Slater, Michael. Charles Dickens: A Life Defined by Writing. New Haven and London: Yale U. P., 2009.

Last modified 17 June 2019