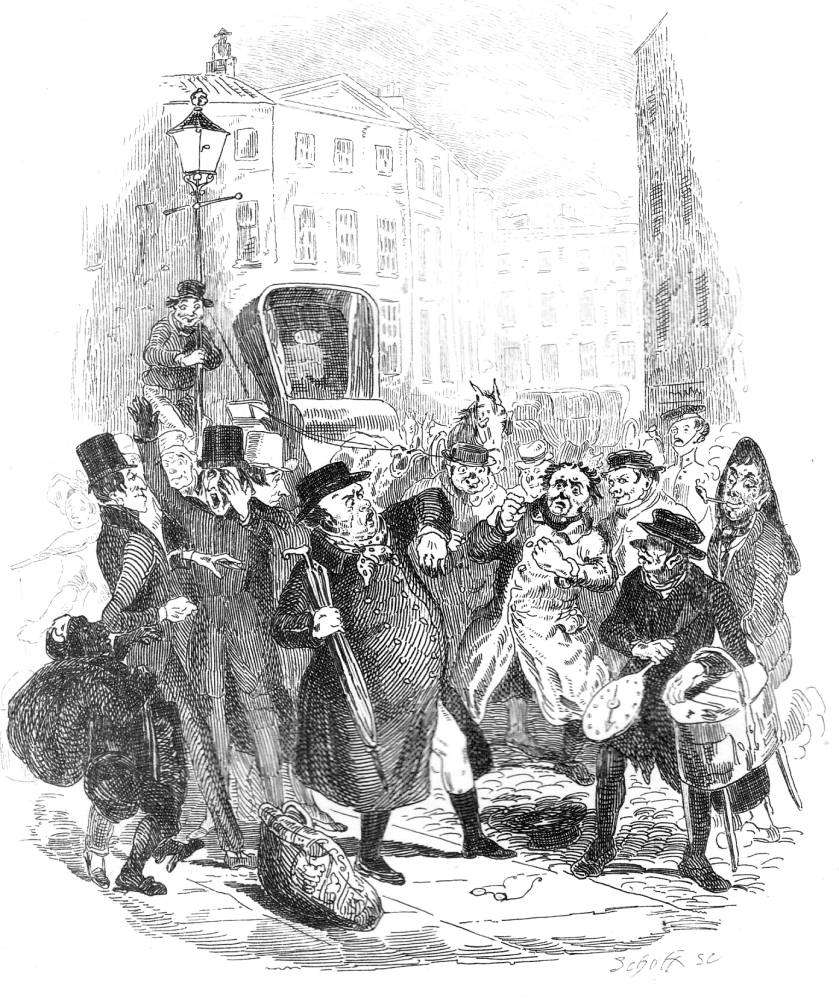

The Pugnacious Cabman

Robert Seymour

1836

Chapter 1, Pickwick Papers by Charles Dickens

Details & Relevant Material

[Click on image to enlarge it]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[Victorian Web Home —> Visual Arts —> Illustration —> Robert Seymour —> Next]

The Pugnacious Cabman

Robert Seymour

1836

Chapter 1, Pickwick Papers by Charles Dickens

Details & Relevant Material

[Click on image to enlarge it]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one. ]

Dickens, having objected to William Hall's suggestions about penning the adventures of a "Nimrod Club," now began to direct the narrative in a direction different from Robert Seymour's original conception In "The Pugnacious Cabman," we revert to the streets of London, the comic milieu of Sketches by Boz. The date is 13 May 1827, and the setting is the Golden Cross, where Tupman, Snodgrass, and Winkle — the core Pickwickians — have been awaiting their chief.

Asa Collins and Guiliano note, the vehicle that Pickwick has hired (background, centre) is not the old-fashioned, heavy hackney coach of eighteenth-century London, but the new, light, one-horse equipage originally called a "cabriolet," the term used in Paris. The English, however, quickly reduced the elegant French expression to "cab," and so Pickwick's belligerent driver (in the white duster, right of centre) is a "cabman," who sits when driving on a perch on the right-hand side, so that passenger and driver might easily converse, as Pickwick and his driver do on the way to the Golden Cross coaching inn. This destination reinforces the fact that the date of the action is in the decade previous to the serial's publication, for the inn disappeared in 1829 to make way for the nation's tribute to the heroic Lord Nelson, Trafalgar Square, "the old Golden Cross Hotel standing on what was to be the site of Nelson's Column" (Collins and Guiliano 24, note 4).

"Would anybody believe," continued the cab–driver, appealing to the crowd, "would anybody believe as an informer'ud go about in a man's cab, not only takin' down his number, but ev'ry word he says into the bargain' (a light flashed upon Mr. Pickwick — it was the note–book).

"Did he though?" inquired another cabman.

"Yes, did he," replied the first; "and then arter aggerawatin' me to assault him, gets three witnesses here to prove it. But I'll give it him, if I've six months for it. Come on!" and the cabman dashed his hat upon the ground, with a reckless disregard of his own private property, and knocked Mr. Pickwick's spectacles off, and followed up the attack with a blow on Mr. Pickwick's nose, and another on Mr. Pickwick's chest, and a third in Mr. Snodgrass's eye, and a fourth, by way of variety, in Mr. Tupman's waistcoat, and then danced into the road, and then back again to the pavement, and finally dashed the whole temporary supply of breath out of Mr. Winkle's body; and all in half-a-dozen seconds. [chapter 2, pp. 5-6 in the Boston ed.]

Nothing in the initial illustration prompts a reader's sympathy with any of the characters, and the illustrator fails to suggest a precise narrative moment for realisation, other than the visual allusion to Pickwick's having one hand in his coat tails.

Despite its official title, "The Pugnacious Cabman," this second Seymour illustration might well be described as "The First Appearance of Alfred Jingle." What is odd about Seymour's construction of the scene in the street as a mob gathers to watch the altercation between Pickwick and his henchmen on the one hand and the indignant cab-driver on the other is that the viewer cannot readily determine which of the many figures is that of Alfred Jingle, whom the text describes as wearing a distinctive green overcoat. Since this scene introduces the reader to this significant and recurring character, one would expect that Seymour would have granted him much greater prominence. Jingle's is one of those Dickens characters readily identifiable by his distinctive voice, principally by his cynical tone and staccato syntax, but Seymour has failed to find a visual equivalent for that unique voice. Since Seymour clearly realises Jingle in "Dr. Slammer's Defiance," and Phiz later provides a fairly satisfactory rendering of Jingle in the Fleet Prison, one way of identifying Jingle with certainty in the early Seymour illustration is to compare Jingle's form and face in "Dr. Slammer's Defiance [of Jingle]", and that of Jingle in Phiz's "The Discovery of Jingle in the Fleet" with that of the characters in the foreground of this second illustration. The out-of-work actor and confidence man has a long, lean appearance and perpetually smirking expression (to say nothing of a prominent nose) that should render him instantly recognisable, but nobody in the congested scene resembles either the Jingle of "Dr. Slammer's Defiance" or "The Discovery of Jingle in the Fleet." This would seem to be an oversight on Seymour's part, but Dickens may not have briefed him on the importance of clearly depicting Jingle, who is probably the man in the white beaver immediately behind Pickwick, to the left. The angry cab-driver, then, would by elimination be the figure in the "duster" in the space between the carefully described hot-pie man (right) and Pickwick (centre), his fists raised in defiance. Otherwise, Seymour has conveyed the essential chaos and the elegant urban backdrop effectively, even to the point of having one curious bystander climb a lamp standard to get a better view. Here we do not have the benign, charming Pickwick of the later illustrations, by an angry, vociferous Pickwick who stands up for himself, even when confronted by a mob mistrustful of his motives and suspecting him of being a police informant.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State U. P., 1980.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File and Checkmark Books, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. Pickwick Papers (1836-37). Il. Hablot Knight Browne. The Charles Dickens Edition. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867.

Dickens, Charles. Pickwick Papers (1836-37). Il. Hablot Knight Browne. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1873.

Dickens, Charles. Pickwick Papers (1836-37). Il. Thomas Nast. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Bros., 1873.

Guiliano, Edward, and Philip Collins, eds. The Annotated Dickens. Vol. 1. New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1986.

Hammerton, J. A. The Dickens Picture-Book. London: Educational Book Co., 1910.

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington & London: Indiana U.P., 1978.

Last modified 21 January 2012