f Franklin is remembered at all, then it is only as a ‘Germanic artist’, one of several designers of the eighteen thirties and forties who championed the graphic styles of illustrators such as Alfred Rethel and promoted the conventions of the Munich School. Franklin was in the forefront of this movement. In the words of an Athenaeum reviewer, the artist has ‘studied that which is German so deeply, that it has become a part of himself’ (1846; qtd. Buchanan-Brown, p.219).

Some of this was a matter of the illustrator’s own taste, and he must have seen publications such as Rethel’s Das Nibelungenlied (1840) and August Moritz Retzsch Retzsch’s outline books, which were hugely popular in early Victorian culture and became a fashionable addition to every middle-class library. Like H. C. Selous, John Tenniel, Daniel Maclise, Frederick R. Pickersgill and others working in the German style, Franklin found a niche responding to the taste of a large audience. His approach to the idiom was also like that of his contemporaries, who typically responded to the two main branches of Germanic design: the outline style of Retzsch; and the rusticity of Rethel, Neurether and Hasenclever.

Franklin produced three outline books. The Ancient Ballad of Chevy Chase (1836), was followed by Tableaux from Crichton; a Romance by W.H.A. (1837), and he completed the set with Wertheim’s Bible Cartoons [1842]. Each of these is modelled on Retzsch and as in the case of Selous he produces what at the time was claimed by some as a ‘British interpretation’ and condemned by others as plagiarism. Tableaux from Crichton was the subject of exactly this controversy; some reviewers praised its appropriation of a Germanic visual language, while others dismissed it as simple copying. The Athenaeum was scornful, noting how ‘many of the heads, attitudes, and costumes, are almost, if not altogether, borrowed from Retzsch’ (qtd. Buchanan-Brown, p.114). Franklin’s response to this criticism is unknown, but we can say that the ‘outline style’ was for him very much a passing phase. He was more comfortable as a practitioner of Germanic rusticity, and this became his most characteristic style.

His development of his own version of this idiom was greatly assisted by patronage of S. C. Hall, who edited The Book of British Ballads, and the publisher James Burns. Both were advocates of the style derived from Rethel, and both commissioned Franklin to practise illustration in the preferred manner. Hall gave Franklin the opportunity to present a detailed series in the Ballads, and Burns used him as a mainstay in The Book of Nursery Tales (1844–45) and Poems and Pictures (1846). Buchanan-Brown has provided a general analysis of these and other works (pp. 216–219), but it is instructive to consider one of Franklin’s characteristic images in detail.

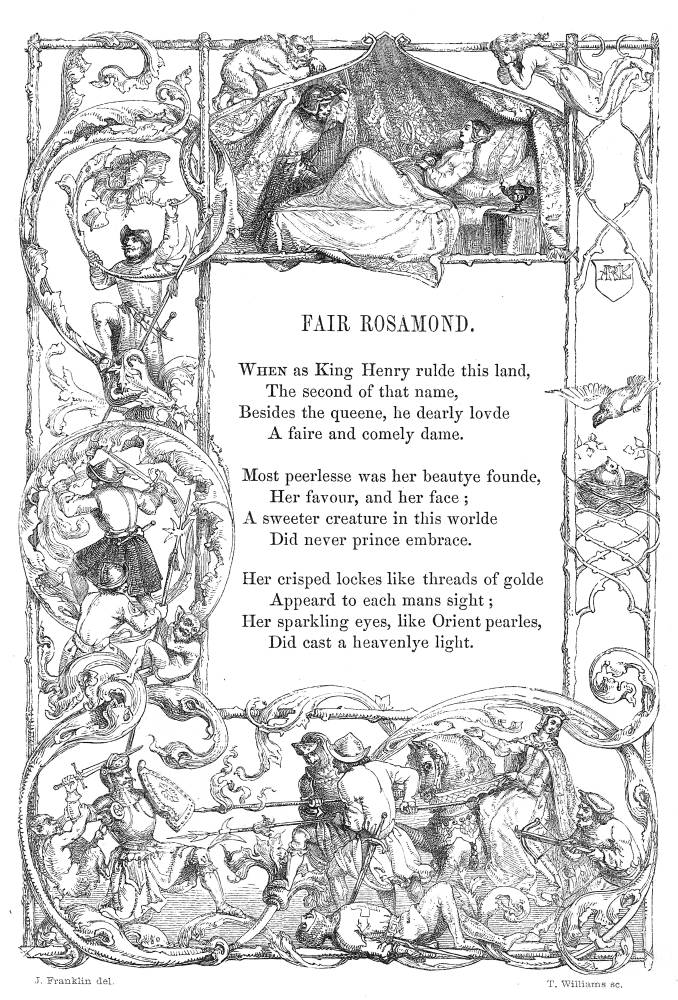

Fair Rosamund. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

One of the best of these is his border surrounding the text for ‘Fair Rosamund’ in The Book of British Ballads (p. 22). This is the usual combination of drama and ornament. The text is framed by a rustic pergola, and within this a foliate, a sort of swirling leaf-stem, embraces a series of characters engaged in a dramatic event. On the lower margin are a knight in armour fighting three soldiers, with Rosamund on horse-back to the right, and a figure (presumably dead) lying beneath their feet. Positioned within a frieze, these characters move strongly from right to left; the eye is then directed up the left hand side by figures climbing through and up the floral arabesque; and is finally focused on Rosamund in bed as if she were the Sleeping Beauty, with her lover, Henry II, opening a curtain to look at her. Events from the poem are thus figured as part of the design on the opening page; proleptic in effect, they build anticipation by introducing the key incidents before they are encountered in the text.

Franklin’s design is presented, in other words, as an efficient illustration that is also pleasingly decorative. The tone is characteristically playful, and Franklin experiments with the overlap between the purely ornamental and the representation of narrative. One of his most interesting visual conceits is the intermingling of stylistic ornament and the reality implied in the treatment of the characters. The two are amusingly brought together in the passages showing the soldiers climbing up the border – as if it literally real and occupies the same space as they do. There is also humour in the small details, notably in the figure of a bird returning to its mate sitting on brood in a nest, a comment, perhaps, on the King coming to visit his lover. Such inventiveness features throughout The Book of British Ballads, and there are many other examples of Franklin’s experimentation with the rustic border, which he works up into a condition of mannerism and fantasy.

Inventive in all that he did and responsive to the demands of the text, Franklin’s work both here and in his work for Ainsworth is worthy of acclaim. By turns expressionistic and decorative, dramatic and droll, his art deserves much greater recognition than has yet been accorded.

Bibliography

Hall, S.C. The Book of British Ballads . London: Bohn, n.d. [1860; first published 1842].

Last modified 20 February 2013