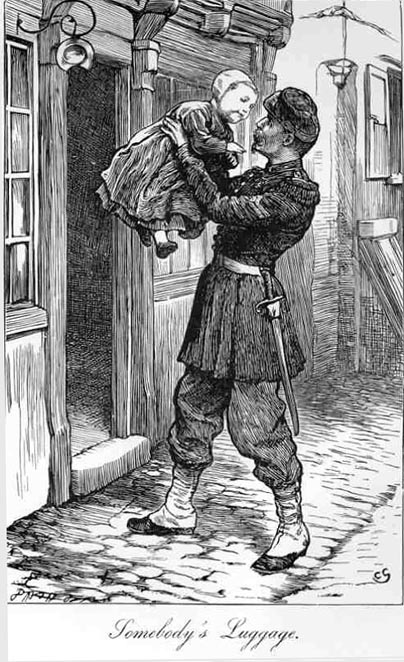

"Little Bebelle and The Corporal"

Sol Eytinge, Junior

1867

Wood-engraving

10 cm high x 7.4 cm wide

The initial illustration for Dickens's "Somebody's Luggage," "His Boots" in Additional Christmas Stories in the Ticknor & Fields (Boston, 1867) Diamond Edition, facing page 218.

[Click on image to enlarge it and mouse over text for links.]

The sentimental narrative of the orphan adopted by a French corporal and, upon his death, by an aloof and psychologically damaged Englishman living in France, Mr. Langley. [Commentary continues below.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated

A mere mite of a girl stood on the steps of the Barber's shop, looking across the Place. A mere baby, one might call her, dressed in the close white linen cap which small French country children wear (like the children in Dutch pictures), and in a frock of homespun blue, that had no shape except where it was tied round her little fat throat. So that, being naturally short and round all over, she looked, behind, as if she had been cut off at her natural waist, and had had her head neatly fitted on it.

"There's the child, though."

To judge from the way in which the dimpled hand was rubbing the eyes, the eyes had been closed in a nap, and were newly opened. But they seemed to be looking so intently across the Place, that the Englishman looked in the same direction.

"Oh!" said he presently. "I thought as much. The Corporal's there."

The Corporal, a smart figure of a man of thirty, perhaps a thought under the middle size, but very neatly made, — a sunburnt Corporal with a brown peaked beard, — faced about at the moment, addressing voluble words of instruction to the squad in hand. Nothing was amiss or awry about the Corporal. A lithe and nimble Corporal, quite complete, from the sparkling dark eyes under his knowing uniform cap to his sparkling white gaiters. The very image and presentment of a Corporal of his country's army, in the line of his shoulders, the line of his waist, the broadest line of his Bloomer trousers, and their narrowest line at the calf of his leg. ["His Boots," p. 219]

At bottom, it was for this reason, more than for any other, that Mr. The Englishman took it extremely ill that Corporal Théophile should be so devoted to little Bebelle, the child at the Barber’s shop. In an unlucky moment he had chanced to say to himself, “Why, confound the fellow, he is not her father!” There was a sharp sting in the speech which ran into him suddenly, and put him in a worse mood. So he had National Participled the unconscious Corporal with most hearty emphasis, and had made up his mind to think no more about such a mountebank.

But it came to pass that the Corporal was not to be dismissed. If he had known the most delicate fibres of the Englishman's mind, instead of knowing nothing on earth about him, and if he had been the most obstinate Corporal in the Grand Army of France, instead of being the most obliging, he could not have planted himself with more determined immovability plump in the midst of all the Englishman's thoughts. Not only so, but he seemed to be always in his view. Mr. The Englishman had but to look out of window, to look upon the Corporal with little Bebelle. He had but to go for a walk, and there was the Corporal walking with Bebelle. He had but to come home again, disgusted, and the Corporal and Bebelle were at home before him. If he looked out at his back windows early in the morning, the Corporal was in the Barber's back yard, washing and dressing and brushing Bebelle. If he took refuge at his front windows, the Corporal brought his breakfast out into the Place, and shared it there with Bebelle. Always Corporal and always Bebelle. Never Corporal without Bebelle. Never Bebelle without Corporal. [p. 220]

Commentary

Whereas E. G. Dalziel in his Household Edition illustration focuses on the minor, comic characters of the sentimental tale for Christmas time, Madame Bouclet (Langley's landlady) and her lodger, Monsieur Mutuel, whose verbal sparring opens the story, Eytinge focuses on the manly corporal and his diminutive charge, the characters whose fortunes constitute the main thrust of the story. Abbey in his 1876 illustration maintains the sentimental strain by realising the moment when the aloof Englishman discovers little Bebelle at the corporal's grave. In contrast, Harry Furniss in the Charles Dickens Library Edition focuses instead on Christopher, The old waiter who serves as the narrator of the frame of Somebody's Luggage (1862). Eytinge brings the eye well forward to admire the lean, masculine figure of the Corporal, who tenderly brushes the head of the toddler by his side; however, the illustrator also uses the figure of the child to carry the eye backward to the dark-coated, middle-aged bourgeois observing them, surely the solitary Englishman, Mr. Langley. Perhaps the best modelled and most emotionally satisfying illustration for "His Boots" is Charles Green's 1868 wood-engraving of the uniformed Corporal playing with Bebelle in an old street in the "dull old fortified French town" (215), probably Boulogne, where Dickens's sons went to school and with which Dickens would have been familiar from his trips to nearby Condette with his mistress Ellen Ternan in the early 1860s — precisely when this story was written. The ten-part framed tale Somebody's Luggage, of which this was the second part, first appeared in the Christmas Story for 1862 in All the Year Round.

Household Edition (1876-77) and Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910) Illustrations Relevant to "His Boots"

Later Editions. Left: E. A. Abbey's "Bebelle! My Little one!" (1876). Centre: E. G. Dalziel's "But it is not impossible that you are a pig!" retorted Madame Bouclet (1877). Right: Charles Green's "Somebody's Luggage" (1868). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1988.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books and The Uncommercial Traveller. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. 10.

Dickens, Charles. The Uncommercial Traveller and Additional Christmas Stories. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Junior. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Stories. Illustrated by Charles Green. TheIllustrated Library Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1868, rpt. in the Centenary Edition of Chapman & Hall and Charles Scribner's Sons (1911).

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Stories. Illustrated by E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Stories from "Household Words" and "All the Year Round". Illustrated by E. G. Dalziel. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1877.

Parker, David. "Christmas Books and Stories, 1844 to 1854." Christmas and Charles Dickens. New York: AMS Press, 2005. Pp. 221-282.

Scenes and characters from the works of Charles Dickens; being eight hundred and sixty-six drawings, by Fred Barnard, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz); J. Mahoney; Charles Green; A. B. Frost; Gorgon Thomson; J. McL. Ralston; H. French; E. G. Dalziel; F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes; printed from the original woodblocks engraved for "The Household Edition.". New York: Chapman and Hall, 1908. Copy in the Robarts Library, University of Toronto.

Thomas, Deborah A. Dickens and The Short Story. Philadelphia: U. Pennsylvania Press, 1982.

Victorian

Web

Illus-

tration

Charles

Dickens

Sol

Eytinge

Next

Last modified 3 April 2014