He seized me by the chin

A. A. Dixon

1905

Watercolour; lithograph

12.8 cm high x 8.5 cm wide

Illustration for the Collins Pocket Edition, facing the title-page

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham

[Victorian Web Home —> Visual Arts —> Illustration —> A. A. Dixon —> Great Expectations —> Next]

He seized me by the chin

A. A. Dixon

1905

Watercolour; lithograph

12.8 cm high x 8.5 cm wide

Illustration for the Collins Pocket Edition, facing the title-page

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham

[You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one. ]

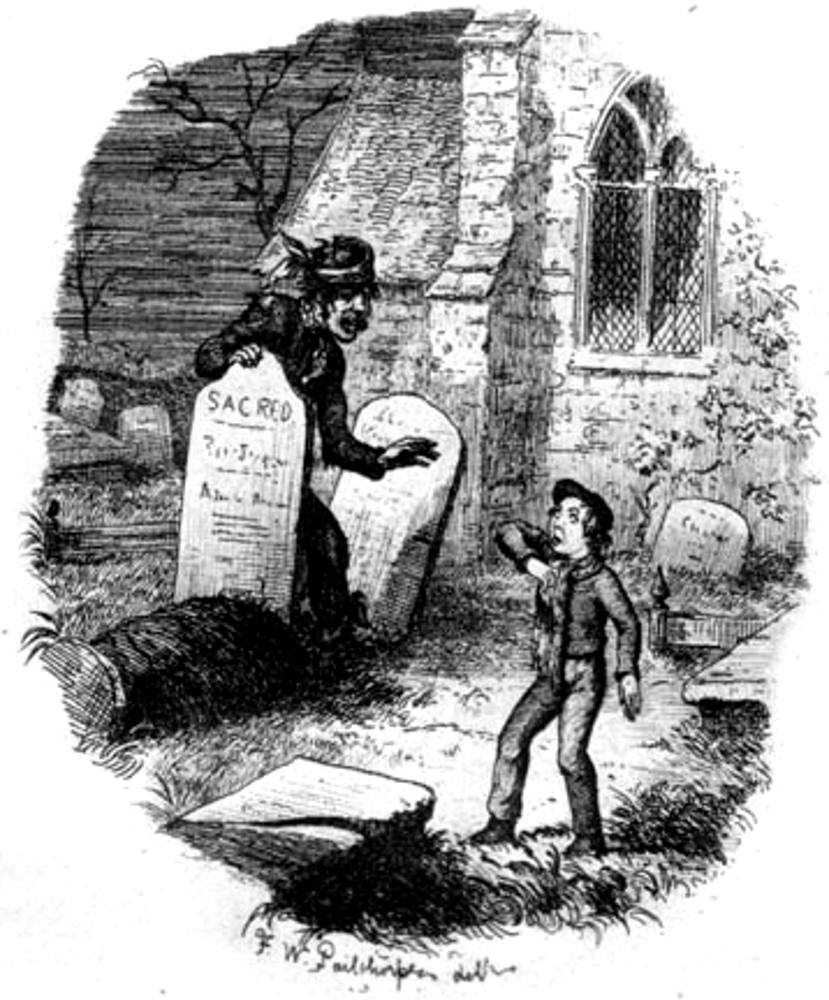

Hold your noise!" cried a terrible voice, as a man started up from among the graves at the side of the church porch. "Keep still, you little devil, or I'll cut your throat!"

A fearful man, all in coarse gray, with a great iron on his leg. A man with no hat, and with broken shoes, and with an old rag tied round his head. A man who had been soaked in water, and smothered in mud, and lamed by stones, and cut by flints, and stung by nettles, and torn by briars; who limped, and shivered, and glared, and growled; and whose teeth chattered in his head as he seized me by the chin. [Chapter 1, page 6]

One of the memorable scenes in English literature is that in which Pip encounters an escaped convict in the churchyard near his home on the Medway marshes, the actual counterpart of the physical setting being the precincts of the parish church of St. James at Cooling, Kent, within an easy walk of Dickens's country home, Gadshill Place. So stunning an opening to the novel made it a logical choice for the opening illustration in almost every nineteenth-century edition, beginning with the Harper's Weekly serialization. In the initial volume edition, American illustrator Felix O. C. Darley elected to realise the apprehension of the struggling convicts on the marshes shortly afterward, a highly dramatic moment that conveniently permitted him to introduce blacksmith Joe Gargery and the aristocratic criminal Compeyson, as well as Pip and Magwitch. Whereas, however, Darley had only two frontispieces with which to work and introduced only four principal characters (Joe, Pip, Magwitch, and Compeyson), most of the other illustrators of nineteenth-century editions of the novel have been able to introduce a much greater range of characters because their pictorial programs were much longer. Even Dixon, with just seven illustrations to complete, has been able to emphasize the roles of Pip, Magwitch, Estella, Miss Havisham, Joe, Jaggers, and Orlick, necessarily omitting such secondary characters as Herbert, Pumblechook, Wopsle, and Wemmick. Another such limited but effective program is that of Dickens's chosen illustrator for the volume editions of 1862 and 1864, Marcus Stone.

Like Stone, but unlike the book's first illustrator, John McLenan, Dixon had likely read the entire novel in advance of illustrating it, and therefore imnformed each of his illustrations with a thorough knowledge of the plot and the characters' places within it. Appreciating, for example, the importance of establishing the protagonist-narrator as a lonely child and of the fateful figure of the convict in the boy's life, A. A. Dixon in the 1905 Collins' Pocket Edition depicts both the setting, the figures, and their juxtaposition with almost photographic precision — in contrast to the impressionist verve and dynamism of the opening scene by Harry Furniss in The Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910). Dixon is faithful to Dickens's text: the church tower and graves, with the Pirrip headstone to the left, correspond exactly with Pip's narrative. In fact, Dixon may have even taken the trouble to visit Cooling in preparing his illustrations since the village church with its square tower and side-chapel corresponds fairly closely with the actual building six miles north-west of Rochester. On the other hand, Pip's reference to a steeple on the building is not supported by the tower at Cooling, but suggests instead that Dickens had in mind the church of St. Mary at Lower Higham nearby.

However, Dixon fails to show Magwitch's muddy condition, despite the ragged condition of his grey penal uniform — nor does the figure exhibit the nettles, briars, and cuts that the narrator so vividly describes. Dixon's Magwitch is not, like Furnss's convict, savage or violent, but merely curious as he begins to interrogate the boy. Perhaps the result of historical research into incarceration practices to which transported felons were subjected, the leg-irons in this picture are somewhat different from the leg-irons and manacles one sees in the other illustrations.

Paroissien cites an 1829 description of the manacling of the legs of transportees:

On their arrival at the hulks, from different gaols, [convicts] are immediately stripped and washed, clothed in coarse grey jackets and breeches [as opposed to trousers], and two irons placed on one of their legs, to which degradation every one must submit, let his previous rank have been what it may. (A Treatise on the Police and Crime of the Metropolis, 1829, 365, quoted in Tobias, 1972, 141) [Paroissien 30]

If the journalist and historian John Wade (1788-1875) just cited is correct, the illustration which corresponds most closely to the actual appearance of a transported felon is that by J. Clayton Clarke ("Kyd")'s Characters from Dickens: Abel Magwitch, in which the illustrator has given him a single leg-iron, but a uniform similar to that worn by Dixon's escaped convict.

Left: John McLenan's "'You young dog!' said the man, licking his lips at me, 'What fat cheeks you ha' got!'". Centre: Sol Eytinge's "Pip and the Convict". Right: F. A. Fraser's "And you know what wittles is?" . [Click on images to enlarge them.]

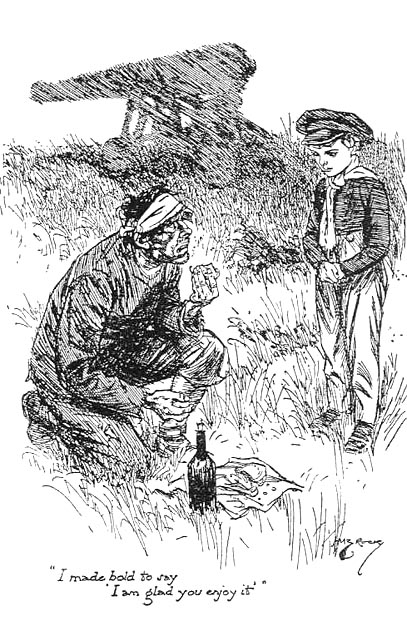

Left: F. W. Pailthorpe's "The Terrible Stranger in the Churchyard". H. M. Brock's "I made bold to say 'I am glad you enjoy it." Center: F. O. C. Darley's "The sergeant ran in first. . . " (1861). Right: Harry Furniss's "Pip's struggle with the escaped convict." (1910). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Dickens, Charles. Great Expectations. Il. John McLenan. Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization 4 (8 December 1860): 773.

Dickens, Charles. Great Expectations. Il. F. O. C. Darley. Volume 1. The Household Edition. New York: James G. Gregory, 1861.

Dickens, Charles. Great Expectations. Il. John McLenan. Philadelphia: T. B. Peterson, 1861.

Dickens, Charles. Great Expectations. Il. Marcus Stone. The Illustrated Library Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1864.

Dickens, Charles. Great Expectations. Il. Sol Eytinge, Junior. Diamond Edition. 14 vols. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867.

Dickens, Charles. Great Expectations. Il. F. A. Fraser. Volume 6 of the Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1876.

Dickens, Charles. Great Expectations. Il. F. W. Pailthorpe. London: Robson & Kerslake, 23 Coventry Street, Haymarket, 1885.

Dickens, Charles. Great Expectations. Il. H. M. Brock. Imperial Edition. 16 vols. London: Gresham Publishing Company [34 Southampton Street, The Strand, London], 1901-3.

Dickens, Charles. Great Expectations. Il. A. A. Dixon. Collins Pocket Edition. London and Glasgow: Collins' Clear-Type Press, 1905.

Dickens, Charles. Great Expectations. Il. Harry Furniss. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol 14.

Dickens, Charles. Great Expectations. Il. Edward Ardizzone. Heritage Edition. New York: Heritage Press, 1939.

Paroissien, David. The Companion to Great Expectations. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood, 2000.

Last modified 24 February 2014