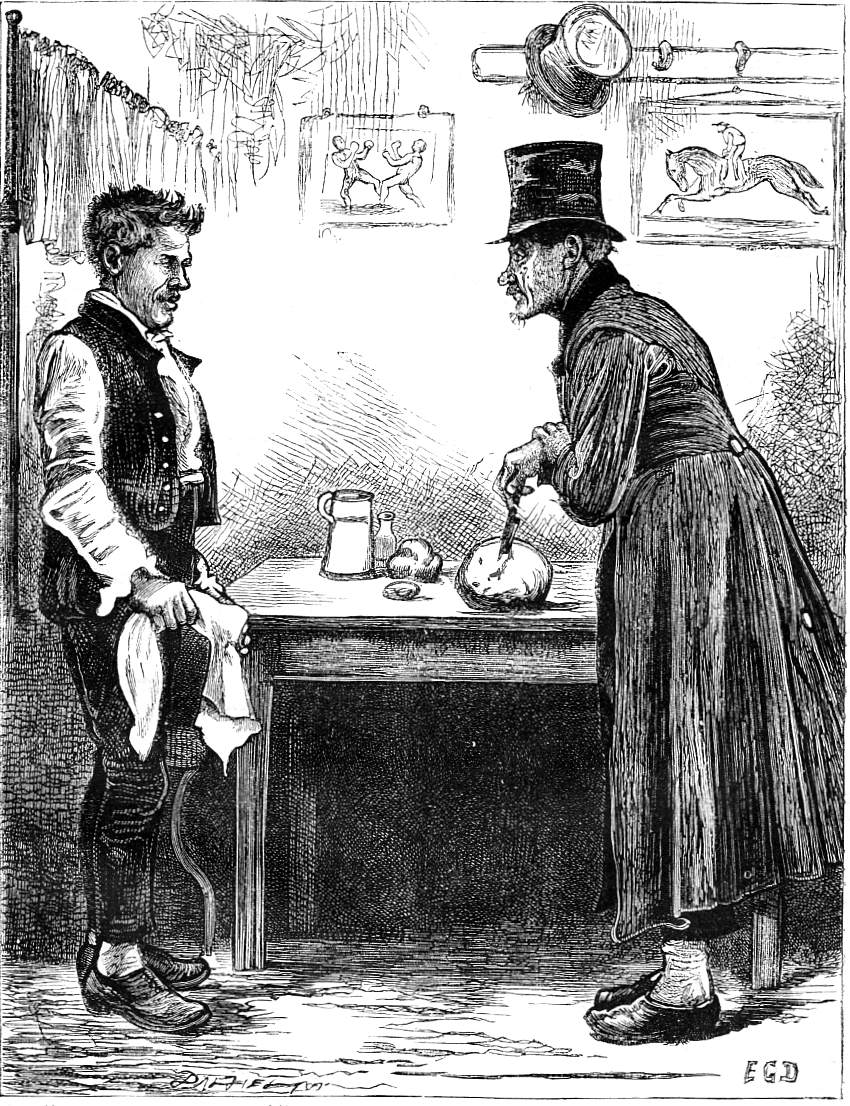

“Am I red tonight?” “You are,” he uncompromisingly answered

Edward G. Dalziel

Wood engraving

Dickens's "Am I red tonight?” “You are,” he uncompromisingly answered," from "Night Walks," chapter 13 in The Uncommercial Traveller

See commentary below

[Click on image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham

[You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Realised

There was early coffee to be got about Covent-garden Market, and that was more company — warm company, too, which was better. Toast of a very substantial quality, was likewise procurable: though the towzled-headed man who made it, in an inner chamber within the coffee-room, hadn't got his coat on yet, and was so heavy with sleep that in every interval of toast and coffee he went off anew behind the partition into complicated cross-roads of choke and snore, and lost his way directly. Into one of these establishments (among the earliest) near Bow-street, there came one morning as I sat over my houseless cup, pondering where to go next, a man in a high and long snuff-coloured coat, and shoes, and, to the best of my belief, nothing else but a hat, who took out of his hat a large cold meat pudding; a meat pudding so large that it was a very tight fit, and brought the lining of the hat out with it. This mysterious man was known by his pudding, for on his entering, the man of sleep brought him a pint of hot tea, a small loaf, and a large knife and fork and plate. Left to himself in his box, he stood the pudding on the bare table, and, instead of cutting it, stabbed it, overhand, with the knife, like a mortal enemy; then took the knife out, wiped it on his sleeve, tore the pudding asunder with his fingers, and ate it all up. The remembrance of this man with the pudding remains with me as the remembrance of the most spectral person my houselessness encountered. Twice only was I in that establishment, and twice I saw him stalk in (as I should say, just out of bed, and presently going back to bed), take out his pudding, stab his pudding, wipe the dagger, and eat his pudding all up. He was a man whose figure promised cadaverousness, but who had an excessively red face, though shaped like a horse's. On the second occasion of my seeing him, he said huskily to the man of sleep, "Am I red to-night?" "You are," he uncompromisingly answered. "My mother," said the spectre, "was a red-faced woman that liked drink, and I looked at her hard when she laid in her coffin, and I took the complexion." Somehow, the pudding seemed an unwholesome pudding after that, and I put myself in its way no more. [65]

Commentary

Charles Dickens, despite his frailty as a child, was a prodigious walker of Olympic proportions, thinking nothing even after age fifty of walking fifteen miles at a stretch. Indeed, in the Uncommercial Traveller essays of the 1860s one receives the impression that Dickens the pedestrian was constantly on the move. "As with daylight walking, nocturnal rambling was a lifelong habit, and since 'Boz's' celebrated sketch of 'The Streets — Night' (1836. . .), the experience had been providing him with inspiration for writing" (Slater and Drew 149). Since the 1840s, moreover, unable to sleep, the writer had walked the London streets by night, observing a very different aspect of the metropolis, and mixing with denizens well below the burgeoning middle class. Slater and Drew cite a letter of March 1846 as an example of Dickens's nocturnal wanderings, precipitated in this case by his planning Dombey and Son. This particular record of post-midnight perambulation is a reflection of a series of walks undertaken in a cold, wet March, which Slater and Drew in the Dent Uniform Edition identify as March 1851, the month in which the writer's father, the quixotic John Dickens, died after a protracted and highly painful illness.

Recalling nights of a decade earlier, "Night Walks" first appeared in All the Year Round on 21 July 1860, As in the other illustrations for The Uncommercial Traveller, here Dalziel does not realize the enigmatic figure of the narrator himself, but lets the reader see what the narrator sees — in this case, the proprietor of an all-night coffee-stand near the Bow Street Police Station, Covent Garden, and a peculiar customer whom Dickens identifies with his nightly meal, a meat pudding, which the odd, "houseless" street-person seems to murder with his utensils before devouring. Here, then, is another terrible, strange figure from what Harry Stone calls "The Night Side of Dickens." Although the Bow Street location is associated with the criminal underclass in many of Dickens's novels, beginning with Oliver Twist (when the Artful Dodger is apprehended), here it is the setting for a Pinteresque nocturnal dialogue between a sleepy shopkeeper and a customer from an alternate reality, the shadowy world of illusion and impending, irrational violence that Amy and Maggy encounter in Little Dorrit when they are locked out of the debtors' prison.

Dalziel's treatment of the pudding-eater from "Night Walks" is far less of a caricature and far more a character study than C. S. Reinhart's ninth Uncommercial Traveller illustration, "And twice I saw him stalk in, take out his pudding, stab his pudding, wipe the dagger, and eat his pudding all up". The American and British Household Edition illustrators seem to have been striving for very different effects with this essay, for Dalziel interprets "Night Walks" as dramatic, "a walk on the wild side," so to speak, whereas Reinhart, having opted for a comic presentation of the manic diner, seems to suggest that "Night Walks" is an exploration of the irrational, bizarre, and even whimsical. The American illustration, foregrounding the diner and his gigantic pudding of cannonball proportions, suggests his benign mania, rendering him almost a cartoon character in the manner of editorial cartoonist Thomas Nast (1841-1907). Dalziel, on the other hand, dramatizes the dialogue between the savage pudding-eater and the more normative coffe-bar owner, humanizing both figures and leaving the reader to judge the extent of the diner's dementia. Whereas there is nothing "cadaverous" about Reinhart's jolly customer, Dalziel's matches in every respect Dickens's description, notably his old top-hat and "high and long snuff-coloured coat." Complementing the masculine nature of the establishment, Dalziel has placed small pictures of boxing and horse-racing just parallel with the customer's top-hat. To save space in the composition, Dalziel has transformed the "partition" between shop and apartment into a mere curtain (upper left).

Other urban scenes

- Poor Mercantile Jack

- Mr. Grazinglands looked in at a pastry cook's window

- Blinking old men . . . let out of workhouses

- He was taken into custody by the police

- Mr. J. Mellows

- Look at this group at a street corner

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. The Uncommercial Traveller, Hard Times, and The Mystery of Edwin Drood. Il. Charles Stanley Reinhart and Luke Fildes. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

Dickens, Charles. The Uncommercial Traveller. Il. Edward Dalziel. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1877.

Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens; being eight hundred and sixty-six drawings, by Fred Barnard, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz); J. Mahoney; Charles Green; A. B. Frost; Gordon Thomson; J. McL. Ralston; H. French; E. G. Dalziel; F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes; printed from the original woodblocks engraved for "The Household Edition." New York: Chapman and Hall, 1908. Copy in the Robarts Library, University of Toronto.

Slater, Michael, and John Drew, eds. Dickens' Journalism: 'The Uncommercial Traveller' and Other Papers 1859-70. The Dent Uniform Edition of Dickens' Journalism, vol. 4. London: J. M. Dent, 2000.

Victorian

Web

Charles

Dickens

Visual

Arts

Illustration

The Dalziel

Brothers

Next