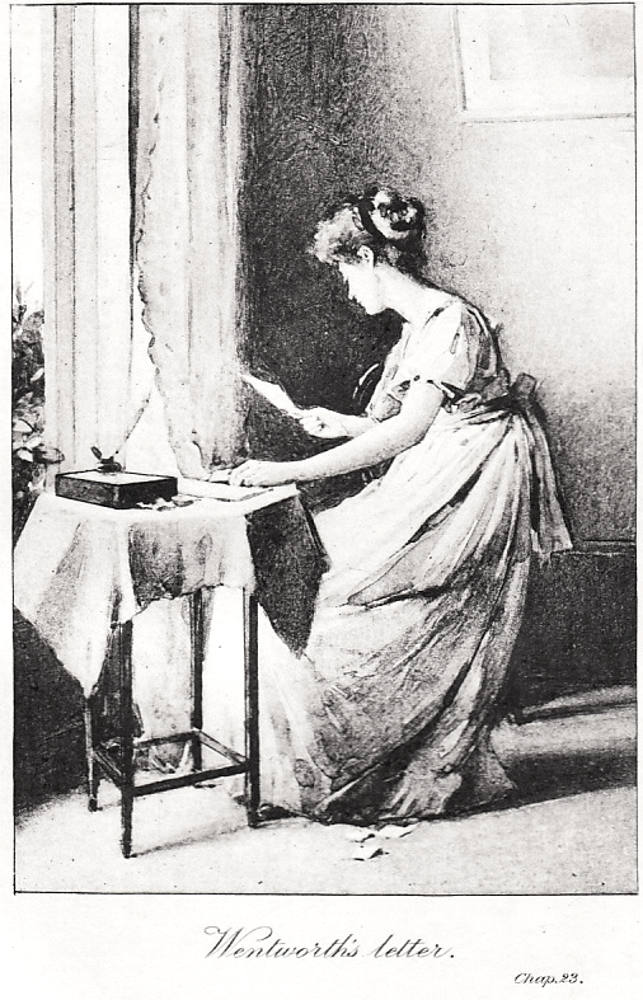

Wentworth's Letter

William Cubitt Cooke

1894

9. high by 6.2 cm wide (3 ½ by 2 ½ inches), framed.

Jane Austen's Persuasion. London: J. M. Dent, 1894. Facing p. 236.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

Wentworth's Letter

William Cubitt Cooke

1894

9. high by 6.2 cm wide (3 ½ by 2 ½ inches), framed.

Jane Austen's Persuasion. London: J. M. Dent, 1894. Facing p. 236.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned it and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

The letter, with a direction hardly legible, to “Miss A. E. —,” was evidently the one which he had been folding so hastily. While supposed to be writing only to Captain Benwick, he had been also addressing her! On the contents of that letter depended all which this world could do for her. Anything was possible, anything might be defied rather than suspense. Mrs. Musgrove had little arrangements of her own at her own table; to their protection she must trust, and sinking into the chair which he had occupied, succeeding to the very spot where he had leaned and written, her eyes devoured the following words:

“I can listen no longer in silence. I must speak to you by such means as are within my reach. You pierce my soul. I am half agony, half hope. Tell me not that I am too late, that such precious feelings are gone for ever. I offer myself to you again with a heart even more your own than when you almost broke it, eight years and a half ago. Dare not say that man forgets sooner than woman, that his love has an earlier death. I have loved none but you. Unjust I may have been, weak and resentful I have been, but never inconstant. You alone have brought me to Bath. For you alone, I think and plan. Have you not seen this? Can you fail to have understood my wishes? I had not waited even these ten days, could I have read your feelings, as I think you must have penetrated mine. I can hardly write. I am every instant hearing something which overpowers me. You sink your voice, but I can distinguish the tones of that voice when they would be lost on others. Too good, too excellent creature! You do us justice, indeed. You do believe that there is true attachment and constancy among men. Believe it to be most fervent, most undeviating, in “F. W.

“I must go, uncertain of my fate; but I shall return hither, or follow your party, as soon as possible. A word, a look, will be enough to decide whether I enter your father’s house this evening or never.”

Such a letter was not to be soon recovered from. Half an hour’s solitude and reflection might have tranquillized her; but the ten minutes only which now passed before she was interrupted, with all the restraints of her situation, could do nothing towards tranquillity. Every moment rather brought fresh agitation. It was overpowering happiness. And before she was beyond the first stage of full sensation, Charles, Mary, and Henrietta all came in. [Chapter 23, pp. 245-246]

In Chapter 23, Anne spends the afternoon with the Musgroves, Captain Harville, Captain Wentworth, and Mrs. Croft. In a parlour conversation with Harville, with Wentworth focussed on writing a letter, Anne argues that women are more constant in love than men, probably because men live "in the world," that is, outside the home. When the others leave Anne in the parlour, she reads the note that Captain Wentworth has discretely left her. Naturally, as the reader expects, he expresses his undying love for Anne (depicted as starting to read Wentworth's note), even after all that she has put him through. The picture prepares us for the moment when, arriving at the letter's conclusion, Anne is overwhelmed by her own feelings.

However, the illustrator's caption does not clearly indicate whether the letter-reader is Anne Elliot or Mrs. Musgrove. Logically, it must be Anne wh is perusing the note that Captain Wentworth has just left for Anne — a hastily written "note" rather than a "letter" in which the young naval officer asserts that he has always loved her, and still hopes to marry her. Thus, Anne's speech earlier abut the constancy of women in love has precipitated Wentworth's declaring his own "constancy" in love. Is this, then, the note that the young woman in the illustration seems to be desultorily perusing? Anne has already read the note (signed “F. W.”) before Mrs. Musgrove returns to the sitting-room, and resumes her place at the writing-table.

Austen, Jane. Persuasion. The Novels of Jane Austen in Ten Volumes. Ed. R. Brimley Johnson. Illustrated by William Cubitt Cooke. London: J. M. Dent, & Co., 1894.

Created 28 August 2025