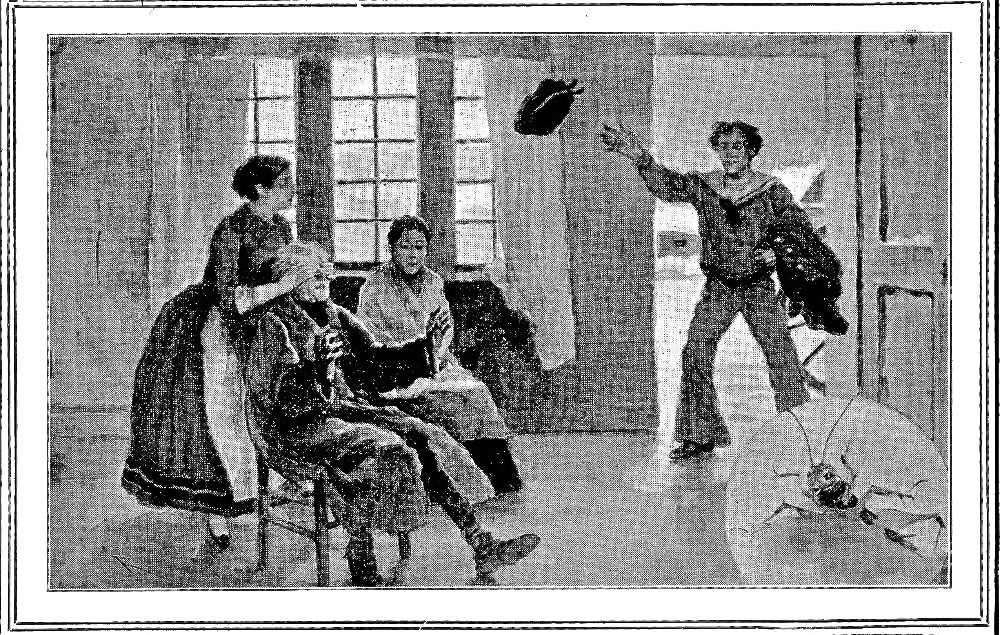

The Wanderer's Return by Luigi Rossi (124). 1912. 6.7 x 11 cm, exclusive of frame. Dickens's The Cricket on the Hearth, A and F Pears.

Context of the Illustration

"They are wheels indeed!" she panted. "Coming nearer! Nearer! Very close! And now you hear them stopping at the garden-gate! And now you hear a step outside the door — the same step, Bertha, is it not! — and now!"—

She uttered a wild cry of uncontrollable delight; and running up to Caleb put her hands upon his eyes, as a young man rushed into the room, and flinging away his hat into the air, came sweeping down upon them.

"Is it over?" cried Dot.

"Yes!"

"Happily over?"

"Yes!"

"Do you recollect the voice, dear Caleb? Did you ever hear the like of it before?" cried Dot.

"If my boy in the Golden South Americas was alive" — said Caleb, trembling.

"He is alive!" shrieked Dot. . . . ["Chirp the Third," 123-25]

Commentary

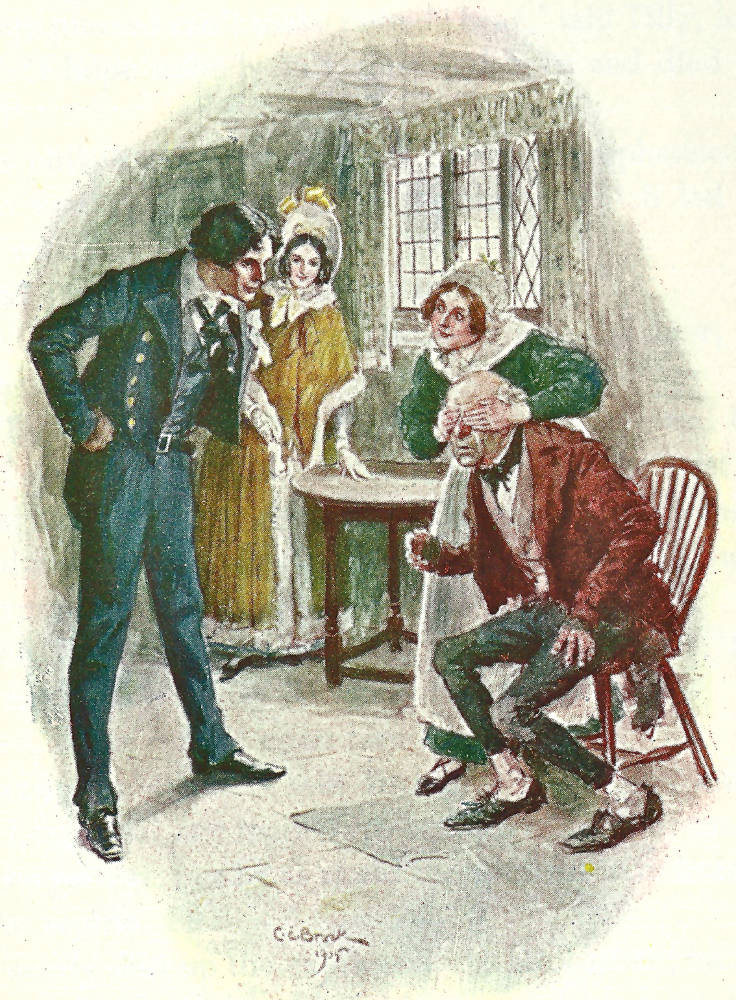

Luigi Rossi responds to main and subplots equally, so that, for example, he focusses here on the subject of Edward's return instead of merely duplicating the narrative-pictorial sequences of previous illustrators such as Fred Barnard (1878) and John Leech and his colleagues (1845) which do not underscore Edward's return. In his program of illustrations for the final volume in the A & F Pears' Christmas Books in the 1912 "Centenary Edition," Rossi takes the opportunity to realize a crucial scene that had only recently appeared in an illustrated edition of the novel, namely Charles Edmund Brock's chromolithograph of Edward's reunion with his father and sister as he announces that he has stolen May from under Tackleton's nose.

However, Rossi frames the reunion scene in a much more theatrical context, as if he is drawing a scene from a stage production such as that at London's Court Theatre earlier that year (No. 132 in Bolton). The scene in which Bertha correctly detects the presence of her long-lost brother, resolving both the main plot (Dot's supposed adultery) and the subplots involving the Plummers, Fieldings, and Tackleton's engagement, was entirely Brock's innovation in 1905. Although both Richard Doyle and Leech in the original edition show the emotional aftermath of the scene in the gallery as John tries to determine how he should act upon this knowledge of his wife's (supposed) infidelity, neither they nor the illustrators of the Household Edition have included this comic recognition scene in which Caleb is visibly straining to hear the the stranger's arrival as he raises his hands as he suddenly recognizes the footfall as his son's.

Again, as with most of the plates in the series, the titles in the "List of Illustrations" (11-12) do not correspond to the captions beneath the illustrations themselves. Here, for example, a quotation augments the short title, and points to the passage that Rossi has realised: "She uttered a wild cry of uncontrollable delight; and running up to Caleb put her hands upon his eyes, as a young man rushed into the room" (repeating a passage that goes from the preceding page, 123, to the present page). Rossi's having included an inset of the cricket in the bottom right corner of the picture suggests that he is trying to reference Dickens's later effusion about the cricket's restoration of domestic harmony in the Perrybingles' home.

The room should look familiar to the viewer as it is same in which the Old Stranger has just discretely announced his true identity to Dot in Mrs. Peerybingle Receives a Shock (page 44). However, the orientation of the room is entirely different so that Rossi shows neither the china dresser nor the table.; rather, he focuses our attention on the doorway and windows, creating an open area uncluttered by tables and chairs. He has effectively set the stage for Dot to rush up to Caleb and cover his eyes as footsteps sound on the cobblestones without. Rossi's image of the parlour is consistent with the earlier leaded panes, the curtained valance and window, but without the table that Brock includes in his version of this scene. The illustrator fills the cottage's flagstone floor to the right with an inset of the cricket. Above the cricket, sailor Edward Plummer (in a trim merchant navy uniform), throws something into the air, which the text indicates: "a young man rushed into the room, and flinging away his hat into the air" (144). Rossi imparts a sense of energy to the illustration by depicting the blue sailor's cap in mid-air, the sailor's arm extended, and one leg well forward as he strides into the parlour. Edward's blind sister, Bertha, whose auditory acuity is the chief component of the scene in Brock's version, sits immobilized beside her father, looking forward. The chief discontinuity between the two scenes in the Peerybingles' parlour, however, remains Edward, whose kinetic image the wide-open door frames as he prepares to meet his father's astonished gaze. Rossi has so positioned the illustration that the reader encounters it and the scene as described in the text simultaneously. However, the intrusive presence of the cricket in the bubble propels the reader back into the text, to discover on the next page what role the domestic spirit plays in the scene; in fact, the narrator delivers this effusion, which the inset image realizes:

All honour to the little creature for her transports! All honour to her tears and laughter, when the three were locked in one another’s arms! All honour to the heartiness with which she met the sunburnt sailor-fellow, with his dark streaming hair, half-way, and never turned her rosy little mouth aside, but suffered him to kiss it, freely, and to press her to his bounding heart! [125]

Rossi has so positioned the bubble that the reader returns to the text to discover what benign influence the spirit and the returned Edward will have in repairing the relationship between John and Dot, so recently imperilled by the prospect of a marital separation. The illustrator thus uses the interpolated insect to set up the final vignettes of the reunited Peerybingles. Rossi here offers a precise parallel to the climactic scene in Boucicault's Dot (1859, 1862) when Edward arrives in his own person rather than in his disguise as the Old Stranger, and announces that he has married May Fielding:

Bertha: No, peace has returned, and I have now an idol for my love no one can take from me. I could not feel happier.

Dot: Yes, you could, and ye will, too. Hark! those bells. What d'ye hear? Listen.

Bertha: I hear shouts, and the sound of wheels; they stop at this door.

Tilly: They're a coming, Mums; everybody's got Married. Here comes the crush — here he be.

Dot: [To Caleb] You should look at him.

Enter Edward: [56/57] 'Tis all over, Dot. She's mine, fast as the parson can make her.

Illustrations for the Other Volumes of the Pears' Centenary Christmas Books (1912)

Each contains about thirty illustrations from original drawings by Charles Green, R. I. — Clement Shorter [1912]

- A Christmas Carol (28 plates) Vol. I (1892)

- The Chimes (31 plates) Vol. II (1894)

- The Battle of Life (28 plates) Vol. IV (1893)

- The Haunted Man (31 plates) Vol. V (1895)

Related Materials

- Dion Boucicault's Adaptation of Charles Dickens's The Cricket on the Hearth (Dot)

- Dion Boucicault's Dot, A Drama in Three Acts (1859, 1862) — Act One

- Dion Boucicault's Dot, A Drama in Three Acts (1859, 1862) — Act Two

- Dion Boucicault's Dot, A Drama in Three Acts (1859, 1862) — Act Three

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Bolton, H. Philip. "The Cricket on the Hearth (1845)."Dickens Dramatized. London & Boston: Mansell & G. K. Hall, 1987. 273-95.

Boucicault, Dion. "Dot: A Drama in Three Acts. 10 April 1862. Add. MS. 53013 (E). Licensed 11/04/1859. The Lord Chamberlain's Manuscript Collection, The British Library, London.

Dickens, Charles. The Cricket on the Hearth. A Fairy Tale of Home. Illustrated by John Leech, Daniel Maclise, Richard Doyle, Clarkson Stanfield, and Edwin Landseer. Engraved by George Dalziel, Edward Dalziel, T. Williams, J. Thompson, R. Graves, and Joseph Swain. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1846 [December 1845].

_____. The Cricket on the Hearth. Illustrated by L. Rossi. London: A & F Pears, 1912.

Morley, Malcolm. "The Cricket on the Stage." Dickensian 48 (1952): 17-24.

Created 28 March 2020

Last modified 13 July 2020