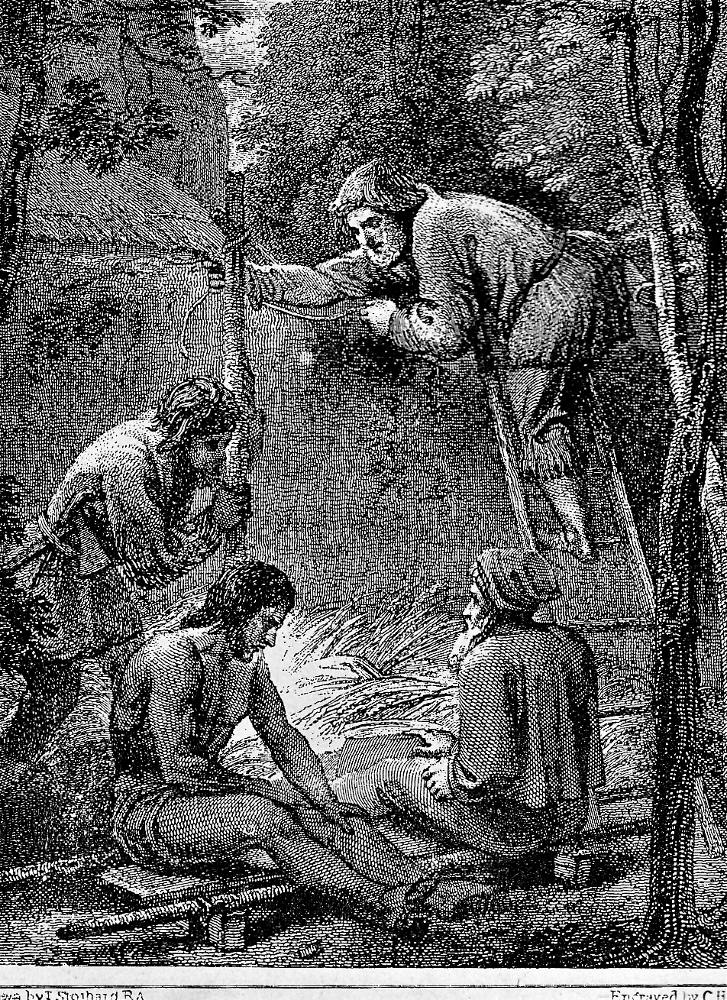

Crusoe Making a Coat (top of page 89) — the volume's twenty-fifth composite wood-block engraving for Defoe's The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner. Related by himself (London: Cassell, Petter, and Galpin, 1863-64). Chapter IX, "A Boat." The illustrator takes full advantage of the potential of the composite wood-block engraving to convey realistic portraiture, showing the protagonist concentrating on his tailoring while his dog observes. From now on both will have hairy clothing! Half-page, framed: 11 cm high x 14.2 cm wide, including the subtle border of leaves. Running head: "Crusoe's Umbrella" (page 91).

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

The Passage Illustrated: Becoming a Jack-of-All-Trades

My clothes, too, began to decay; as to linen, I had had none a good while, except some chequered shirts which I found in the chests of the other seamen, and which I carefully preserved; because many times I could bear no other clothes on but a shirt; and it was a very great help to me that I had, among all the men’s clothes of the ship, almost three dozen of shirts. There were also, indeed, several thick watch-coats of the seamen’s which were left, but they were too hot to wear; and though it is true that the weather was so violently hot that there was no need of clothes, yet I could not go quite naked — no, though I had been inclined to it, which I was not — nor could I abide the thought of it, though I was alone. The reason why I could not go naked was, I could not bear the heat of the sun so well when quite naked as with some clothes on; nay, the very heat frequently blistered my skin: whereas, with a shirt on, the air itself made some motion, and whistling under the shirt, was twofold cooler than without it. No more could I ever bring myself to go out in the heat of the sun without a cap or a hat; the heat of the sun, beating with such violence as it does in that place, would give me the headache presently, by darting so directly on my head, without a cap or hat on, so that I could not bear it; whereas, if I put on my hat it would presently go away.

Upon these views I began to consider about putting the few rags I had, which I called clothes, into some order; I had worn out all the waistcoats I had, and my business was now to try if I could not make jackets out of the great watch-coats which I had by me, and with such other materials as I had; so I set to work, tailoring, or rather, indeed, botching, for I made most piteous work of it. However, I made shift to make two or three new waistcoats, which I hoped would serve me a great while: as for breeches or drawers, I made but a very sorry shift indeed till afterwards.

I have mentioned that I saved the skins of all the creatures that I killed, I mean four-footed ones, and I had them hung up, stretched out with sticks in the sun, by which means some of them were so dry and hard that they were fit for little, but others were very useful. The first thing I made of these was a great cap for my head, with the hair on the outside, to shoot off the rain; and this I performed so well, that after I made me a suit of clothes wholly of these skins — that is to say, a waistcoat, and breeches open at the knees, and both loose, for they were rather wanting to keep me cool than to keep me warm. I must not omit to acknowledge that they were wretchedly made; for if I was a bad carpenter, I was a worse tailor. However, they were such as I made very good shift with, and when I was out, if it happened to rain, the hair of my waistcoat and cap being outermost, I was kept very dry. [Chapter IX, "A Boat," pp. 90-91 ]

Comment

Whereas textual Crusoe feels that he is not succeeding as a tailor and that his haberdashery is not even mediocre, the pictorial Crusoe exudes self-confidence as he skilfully plies his needle — much to the fascination of his dog. The illustrator suggests that Crusoe has already mastered the art of making footwear from animal hides.

Related Material

- Daniel Defoe

- Illustrations of Robinson Crusoe by various artists

- Illustrations of children’s editions

- The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe il. H. M. Brock at Project Gutenberg

- The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe at Project Gutenberg

Parallel Scenes from Stothard (1790), a Children's Book (1818), and Cruikshank (1831)

Left: Stothard's 1790 realisation of the interior of the hut in a later episode, Robinson Crusoe and Friday making a tent to lodge Friday's father and the Spaniard (copper-plate engraving, [Chapter XVI, "Rescue of the Prisoners from the Cannibals"). Centre: A realisation of the interior of the hut, Robinson Crusoe reading the Bible (1818). Right: Cruikshank's study of Crusoe's instructing Poll the Parrot, Crusoe and Poll the Parrot in dialogue (1831). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Bibliography

Defoe, Daniel. The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner. Related by himself. With upwards of One Hundred Illustrations. London: Cassell, Petter, and Galpin, 1863-64.

Last modified 12 March 2018