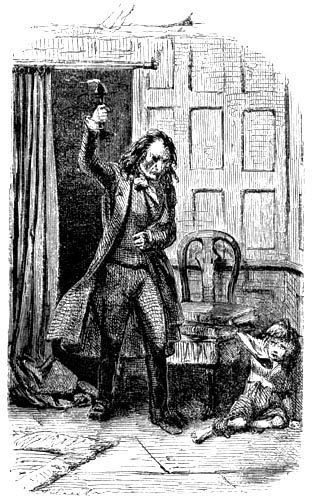

"I'm not a-going to take you there. Let me be, or I'll heave some fire at you!" — Fred Barnard's twentieth-fifth illustration for Dickens's The Christmas Books, p. 184. Engraved by one of the Dalziels, and signed "FB" lower left on the fireplace fender. This illustration foregrounds Dickens's social realism, a persistent strain in the Christmas Books of the 1840s, a wretched time for urban and rural poor alike throughout Europe. 11.3 cm by 14.4 cm (4 ⅜ by 5 ⅝ inches), framed. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Passage Illustrated: Redlaw confronts a savage boy from the streets

The cry responding, and being nearer, he caught up the lamp, and raised a heavy curtain in the wall, by which he was accustomed to pass into and out of the theatre where he lectured, — which adjoined his room. Associated with youth and animation, and a high amphitheatre of faces which his entrance charmed to interest in a moment, it was a ghostly place when all this life was faded out of it, and stared upon him like an emblem of Death.

"Halloa!" he cried. "Halloa! This way! Come to the light!" When, as he held the curtain with one hand, and with the other raised the lamp and tried to pierce the gloom that filled the place, something rushed past him into the room like a wild-cat, and crouched down in a corner.

"What is it?" he said, hastily.

He might have asked "What is it?" even had he seen it well, as presently he did when he stood looking at it gathered up in its corner.

A bundle of tatters, held together by a hand, in size and form almost an infant's, but in its greedy, desperate little clutch, a bad old man's. A face rounded and smoothed by some half-dozen years, but pinched and twisted by the experiences of a life. Bright eyes, but not youthful. Naked feet, beautiful in their childish delicacy, — ugly in the blood and dirt that cracked upon them. A baby savage, a young monster, a child who had never been a child, a creature who might live to take the outward form of man, but who, within, would live and perish a mere beast.

Used, already, to be worried and hunted like a beast, the boy crouched down as he was looked at, and looked back again, and interposed his arm to ward off the expected blow.

"I'll bite," he said, "if you hit me!" ["Chapter I: The Gift Bestowed," The Household Edition by Chapman & Hall, p. 167]

Commentary

Fred Barnard's program of seven illustrations for The Haunted Man and The Ghost's Bargain would be incomplete in terms of the original political and social agenda of Dickens's Christmas Books if it failed to include the savage street boy who reiterates Leech's iconic image of human degredation in Ignorance and Want from A Christmas Carol. Aside from his psychological significance, the ragged Boy is important because he grounds the cautionary tale in the miseries of the Hungry Forties, and reminds modern readers that the year in which Dickens completed the sequence of Christmas Books as "tracts for the times" was the Year of Revolutions throughout Europe, including the still-remembered March of the Chartists on Parliament on 10 April 1848 at Kennington Common. All these symbolic portraits of the effects of urban blight upon its denizens are by a single illustrator, Punch staffer John Leech. As John Butt has noted, the Boy of the last Christmas Book is not merely a repetition of Ignorance in the first, but "a clearly recognizable slum child" (147).

Barnard's illustration of The Boy compared to 1843 and 1848 plates by John Leech.

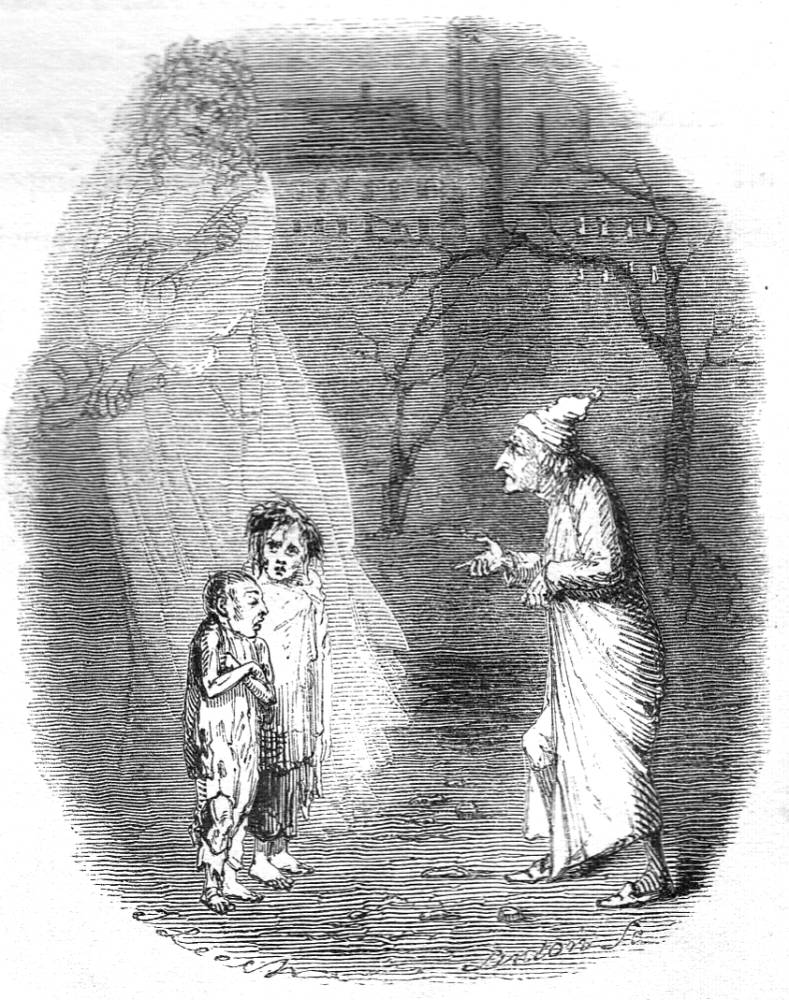

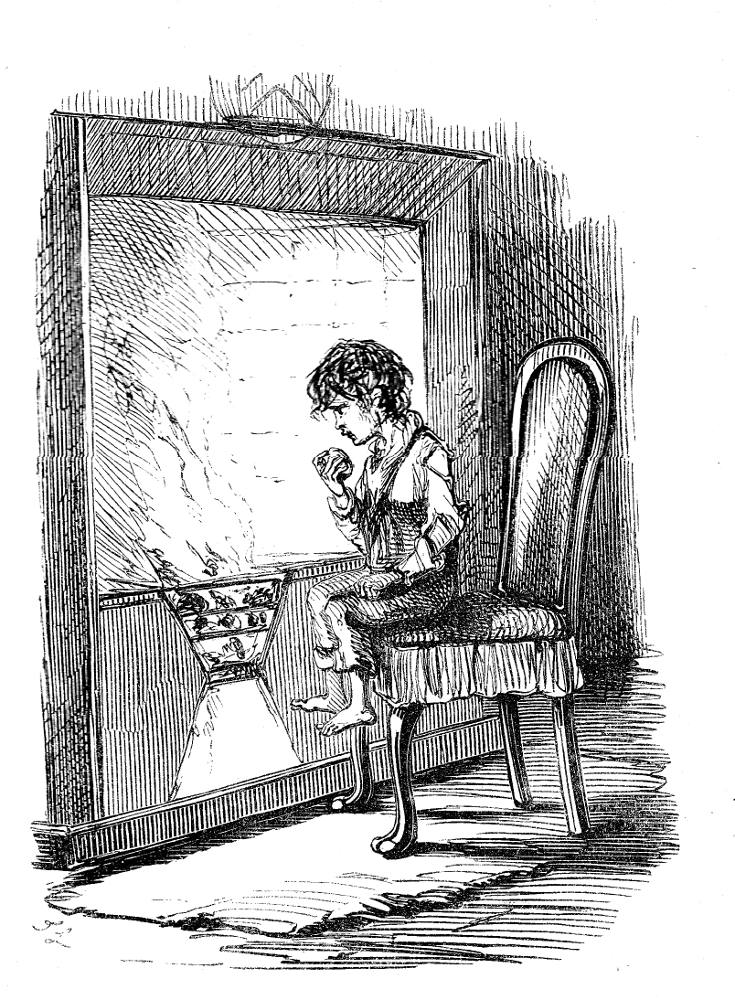

Alternate interpretations of the novella's symbol of poverty and ignorance: Left: John Leech's Ignorance and Want (1843); Centre: John Leech's Redlaw and The Boy; Right: John Leech's The Boy before the Fire (1848).

Instead of showing the savage slum child enjoying himself by the fire, or that same boy's being terrified by Redlaw's entrance (the scenes so effectively realised by John Leech in the original publication), Barnard synthesizes the earlier images of the Boy. On the one hand, he stoops before a roaring fire, pointing a skeletal arm towards the hot coals, reminding the reader of the twelfth illustration in the 1848 volume; on the other hand, he draws back from a cloaked Redlaw in the professor's wainscotted office behind the lecture theatre, as he does in the earlier volume's seventh illustration. Consequently, Barnard has also synthesized Dickens's description of the Boy in "The Gift Bestowed" with Dickens's description of the Boy's second confrontation of Redlaw, in "The Gift Diffused."

In the entirely new series of illustrations for the fifth Christmas Book, Fred Barnard does not simply repeat Leech's savage boy. Rather, he presents savagery in action as the Boy, feeling threatened by the cloaked adult who has suddenly invaded his fireside idyll, threatens the intruder. Thus, under Barnard's hand the Boy from the streets and the slums becomes a figure consistent with the social realism of "Saturday Night in the East End," a famous painting (now lost) which Barnard completed in two years before he illustrated The Christmas Books for Chapman and Hall's Household Edition (1878). The scene, which appealed to Barnard's social conscience, is this:

"Come with me," said the Chemist, "and I'll give you money."

"Come where? and how much will you give?"

"I'll give you more shillings than you ever saw, and bring you back soon. Do you know your way to where you came from?"

"You let me go," returned the boy, suddenly twisting out of his grasp. "I'm not a going to take you there. Let me be, or I'll heave some fire at you!"

He was down before it, and ready, with his savage little hand, to pluck the burning coals out.

What the Chemist had felt, in observing the effect of his charmed influence stealing over those with whom he came in contact, was not nearly equal to the cold vague terror with which he saw this baby- monster put it at defiance. It chilled his blood to look on the immovable impenetrable thing, in the likeness of a child, with its sharp malignant face turned up to his, and its almost infant hand, ready at the bars.

"Listen, boy!" he said. "You shall take me where you please, so that you take me where the people are very miserable or very wicked. I want to do them good, and not to harm them. You shall have money, as I have told you, and I will bring you back. Get up! Come quickly!" He made a hasty step towards the door, afraid of her returning.

"Will you let me walk by myself, and never hold me, nor yet touch me?" said the boy, slowly withdrawing the hand with which he threatened, and beginning to get up.

"I will!"

"And let me go, before, behind, or anyways I like?"

"I will!"

"Give me some money first, then, and go."

The Chemist laid a few shillings, one by one, in his extended hand. To count them was beyond the boy's knowledge, but he said "one," every time, and avariciously looked at each as it was given, and at the donor. He had nowhere to put them, out of his hand, but in his mouth; and he put them there. ["Chapter Two: The Gift Diffused," The Household Edition by Chapman & Hall, p. 180]

The approach here is analeptic in that the reader has already encountered the boy twice, most recently three pages prior to the illustration, so that the reader has already developed a mental image of the urchin against which to compare Barnard's rendering of the "baby-monster" who defies Redlaw in his own intimate space. Barnard gives us effectively the "fiery heat" (180) of the fireplace and the malignant-faced, bare-footed, ragged Boy before it, but fails to suggest the Chemist's "cold vague terror." This creature of the shank end of the Capitalist system is ironically untouched by Redlaw's baleful influence, for he has never known anything but "Sorrow, wrong, and trouble" (181). Barnard realised from his own assessment of the original illustrations that the fireplace as a symbol of domestic comfort could be used to associate such disparate characters as Redlaw and Longford (seen in front of a fireplace in the third of his illustrations), the wild urchin here, and the Phantom in the third-to the-last illustration. As Jane Rabb Cohen remarks of the original Leech illustrations,

the dark, close strokes with which he portrays Redlaw both with the Phantom (I, 401) and the wild boy (I, 408) perfectly capture the requisite sense of strangeness, and the way he positions the child before the fireplace (III, 451) not only recalls Redlaw's posture there in Tenniel's frontispiece (380) as well as his own earlier portrayal (I, 401), but visually reinforces Dickens's linkage of the civilized man and the wild boy. [149]

The Boy, who appears again in Barnard's sequence, as rolled up into a prenatal ball in the scene between the Phantom and Redlaw five pages later, is, if anything, an improvement of Leech's images, with leaner, almost emaciated limbs, a sharp nose and ears suggestive of a ferret's, swirling rags, and a profusion of curly hair. The portrait of the Boy asleep reveals his prominently sunken and bruised eye-sockets that repeat the Phantom's own haunted orbs, as if, without the balm of memory, the psyche is inevitably unbalanced.

Scanned images and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned them and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Allingham, Philip V. "The Illustrations in Dickens's The Haunted Man and The Ghost's Bargain: Public and Private Spheres and Spaces."Dickens Studies Annual 36 (2005), 75-123.

Brereton, D. N. "Introduction." Charles Dickens's Christmas Books. London and Glasgow: Collins Clear-Type Press, n. d.

Butt, John. "Dickens's Christmas Books." Pope, Dickens, and Others. Ed. Geoffrey Carnall. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 1969. 127-148.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and his Original Illustrators. Columbus: University of Ohio Press, 1980.

Cook, James. Bibliography of the Writings of Dickens. London: Frank Kerslake, 1879. As given in Publishers' Circular The English Catalogue of Books.

Dickens, Charles. The Haunted Man and The Ghost's Bargain. Il. John Leech, John Tenniel, Frank Stone, and Clarkson Stanfield. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1848.

Dickens, Charles. The Haunted Man and The Ghost's Bargain. Christmas Stories. Il. E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876. Pp. 143-175.

Dickens, Charles. The Haunted Man and The Ghost's Bargain. Christmas Books. Il. Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878. Pp. 157-200.

Hammerton, J. A. The Dickens Picture-Book. London: Educational Book, 1912.

Kitton, Frederic G. Dickens and His Illustrators. 1899. Rpt. Honolulu: U. Press of the Pacific, 2004.

Parker, David. "Christmas Books and Stories, 1844 to 1854." Christmas and Charles Dickens. New York: AMS Press, 2005. Pp. 221-282.

Slater, Michael. "Introduction to The Haunted Man." Dickens's Christmas Books. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin, 1971. Rpt., 1978. Vol. 2: 235-238.

Slater, Michael. "Notes to The Haunted Man." Dickens's Christmas Books. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin, 1971. Rpt., 1978. Vol. 2: 365-366.

Solberg, Sarah A. "'Text Dropped into the Woodcuts': Dickens' Christmas Books." Dickens Studies Annual 8 (1980): 103-118.

Thomas, Deborah A. Dickens and The Short Story. Philadelphia: U. Pennsylvania Press, 1982.

Created 31 July 2016

Last modified 7 June 2024