"... the subject of women within nineteenth-century museums has not always received the attention it deserves, despite their significant contributions to public institutional histories" — Caroline McCaffrey-Howarth, p. 8.

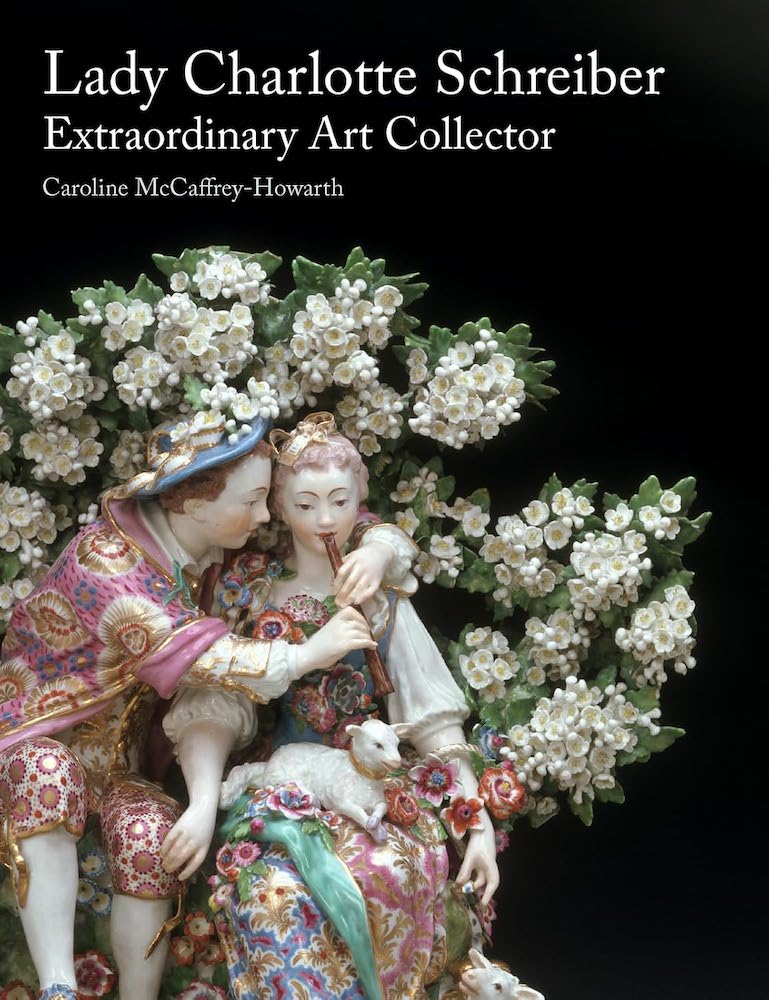

It is indeed one of life’s most cruel ironies that "such a visual person" (149), as Caroline McCaffrey-Howarth rightly describes Lady Charlotte Schreiber (1812-1895), eventually lost her eyesight. Once blind, she spent the last four years of her long life knitting comforters for cabdrivers, but she had definitely left her mark on her century as a collector, translator and philanthropist, and it does not seem excessive to assert that she "subverted gendered norms and challenged Victorian conventions" (7). The volume published by Lund Humphries is actually not the first one to be devoted to her, but the biography written a few years ago by Victoria Owens had a totally different focus, as witnessed by its title – Lady Charlotte Guest, The Exceptional Life of a Female Industrialist (Pen & Sword Books, 2020). Lady Charlotte Schreiber, Extraordinary Art Collector chooses to remember the final married name of the woman who was born as Lady Charlotte Bertie. While telling her whole life from beginning to end, Caroline McCaffrey-Howarth is obviously more interested in her "collecting journey" (11).

Like Victoria Owens, Caroline McCaffrey-Howarth was granted access to the unpublished journals, which young Charlotte started writing when she was just ten, and which she kept until 1891 in a more or less regular manner (some volumes seem to have been deliberately destroyed). Another source of information on her "strategic collecting practice grounded in historical rigour" (17) is the "Ceramic Memoranda Journals" she wrote from 1869 to 1884, and which her son edited after her death: they were published in 1911 under the title Confidences of a Collector of Ceramics & Antiques, in two volumes which excluded her detailed lists of purchases, sales and loans.

Art and literature were present in Charlotte Bertie’s life from a very young age. She was 16 when she taught herself Greek, Latin, French, Arabic and Farsi, feeling a real passion for Eastern cultures. In 1831, during her first season in London, she met Disraeli and Tennyson, and several painters, like Sir David Wilkie and John Martin – visiting the latter’s studio, she commented: "His wildness is quite my own" (19). As a young lady of the upper-class, she had obviously received drawing lessons, but she also practised engraving.

Lady Charlotte Guest around the time of her first marriage, engraved from a portrait by Richard Buckner. Source: Guest I, facing p. xx.

In 1833, she married a wealthy ironmaster twenty-five years her senior and thus became Lady Charlotte Guest. Her husband, who employed several thousand workers, shared her artistic interests, and as she went to live in his native Merthyr Tydfil she became fascinated by the Welsh heritage, taking part in archaeological excavations and wearing the Welsh national dress as often as she could in London. She soon decided to make "Welsh my study, and Aristotle and Chaucer once again my relaxation" (38), which led her to translate the Mabinogion manuscript into English, in competition with the French translation by Villemarqué which was published at the same time as hers; when he wrote his Idylls of the King, Tennyson would base "Geraint and Enid" (Part II of the Idylls) on her work.

She also started collecting Old Master paintings, but her purchases were quickly restricted by a budget which could not equal that of institutional museums. She therefore redirected her antiquarian interests to objects like fans, enamels or ceramics. In 1852, Sir Josiah John Guest died and she rather scandalously remarried in 1855: her second husband was Charles Schrieber, a man fourteen years younger than she was, whom she had employed as a tutor for one of her ten children. In 1865, the art connoisseur turned into "an authority in an unexplored and somewhat unfashionable field" (90) when she started focusing exclusively on English porcelain. She travelling across Europe every year in search of new objects to complete her collection and to provide a better survey of a technique which she proudly discovered had been pioneered in England, before France and Germany. Her advice was sought by other enthusiasts, among whom Queen Victoria herself, and she worked within "a close network of transnational dealers" (79). Being conscious of "the potential agency of small quotidian objects as significant historical records" (108), "whether aesthetically pleasing or not" (112), she saw the "decorative arts as portals to different historical moments" (113).

"Three Unusual Pieces of Staffordshire Salt Glaze Ware" from the Schreiber Collection. The figure on the jug on the right represents "the young Pretender in a tartan dress." Source: Guest I, facing p. 228.

In 1884, her second husband died, and as she had long wanted her collection to belong to the nation, she decided to give it to the South Kensington Museum as a tribute to his memory. The Schreiber Gift, accompanied by a catalogue written by Lady Charlotte herself, was officially accepted in July 1884, the collection reached the museum in November 1885 and was opened to the public on 26 December 1885, the catalogue being only published in February 1886. Thousands of other pieces were later given to the British Museum, including Persian, Chinese and Japanese ceramics.

In 1886, when she was almost 75, Lady Charlotte Schreiber started taking "photographing lessons," having realized the value of photography as visual reference for collectors. A few years before, she had asked Goupil about photogravures to illustrate the catalogue of her bequest. In 1857, she had befriended Julia Margaret Cameron who, however, was still far from being the "celebrated photographer" she would only become in the 1870s, as she was only given her first camera in 1863; it is perhaps a bit daring to assert that "surely [Lady Charlotte’s] knowledge of the medieval past of Wales must have also informed Cameron’s artistic approach" (69).

Beside an engraving after a drawing by G.F Watts and a carte-de-visite portrait by Camille Silvy, Caroline McCaffrey-Howarth’s volume includes the reproduction, on page 36, of a fascinating photograph of Lady Charlotte Guest giving a lecture in Dowlais Central School, which she had built by Sir Charles Barry in 1855. Judging from her bonnet and the clothes of the young men in the foreground, the date (ca 1870) seems a bit too late (especially as she appears to have left Wales after her remarriage) and very few photographs could be taken inside buildings at the time; but sufficient light was apparently provided by the huge pointed window in the background. This extremely bright picture, quite unusual in the mid-nineteenth century, undoubtedly constitutes a fitting tribute to such an exceptional woman.

Links to Related Material

- Iron and Steel Making in South Wales

- Gwendolen and Margaret Davies (later art collectors from Wales)

- Henry Wallis and Ceramics (another collector)

Bibliography

[Illustration source] Guest, Charlotte, Lady, Montague John Guest, Egan Mew and the Victoria and Albert Museum. Lady Charlotte Schreiber's journals: confidences of a collector of ceramics & antiques throughout Britain, France, Holland, Belgium, Spain, Portugal, Turkey, Austria & Germany: from the year 1869 to 1885. Vol I. London: John Lane, 1911. Internet Archive, from a copy in the Getty Research Institute. Web. 28 September 2025. [Note: Caroline McCaffrey-Howarth's book itself is also handsomely illustrated.]

[Book under review] McCaffrey-Howarth, Caroline. Lady Charlotte Schreiber, Extraordinary Art Collector. London: Lund Humphries, 2025. Hardback. 192 pp. £40.00. ISBN: 978-1848226814.

Created 27 September 2025