History, Context and Aesthetics

The Guild of Women Binders was a collective of female artisans who created a variety of fine bindings in the period from 1898 to 1904. The Guild was set up by Frank (Francis) Karslake (1864–1917), an antiquarian and second-hand bookseller with a shop in Charing Cross, London. Karslake viewed several bindings by women binders at the ‘Victorian Era Exhibition’ at Earl’s Court in 1897, and decided to promote the work he had seen as exemplars of a new interest in handicraft. ‘The Exhibition of Artistic Book-bindings by Women’ was displayed at his shop (November 1897–February 1898), and thereafter he decided to act as an agent for several of the binders. The final stage was the creation of the Guild in May 1898, which he based partly in his bookselling premises and partly at the Hampstead Bindery, in which he also had a financial interest. The venture had two dimensions: Karslake sold the work of experienced binders such as Florence de Rheims, and established the Guild as a teaching institution which trained new entrants. Students were instructed in the principles of handicraft binding and employed on a piece-meal basis once their studies were completed.

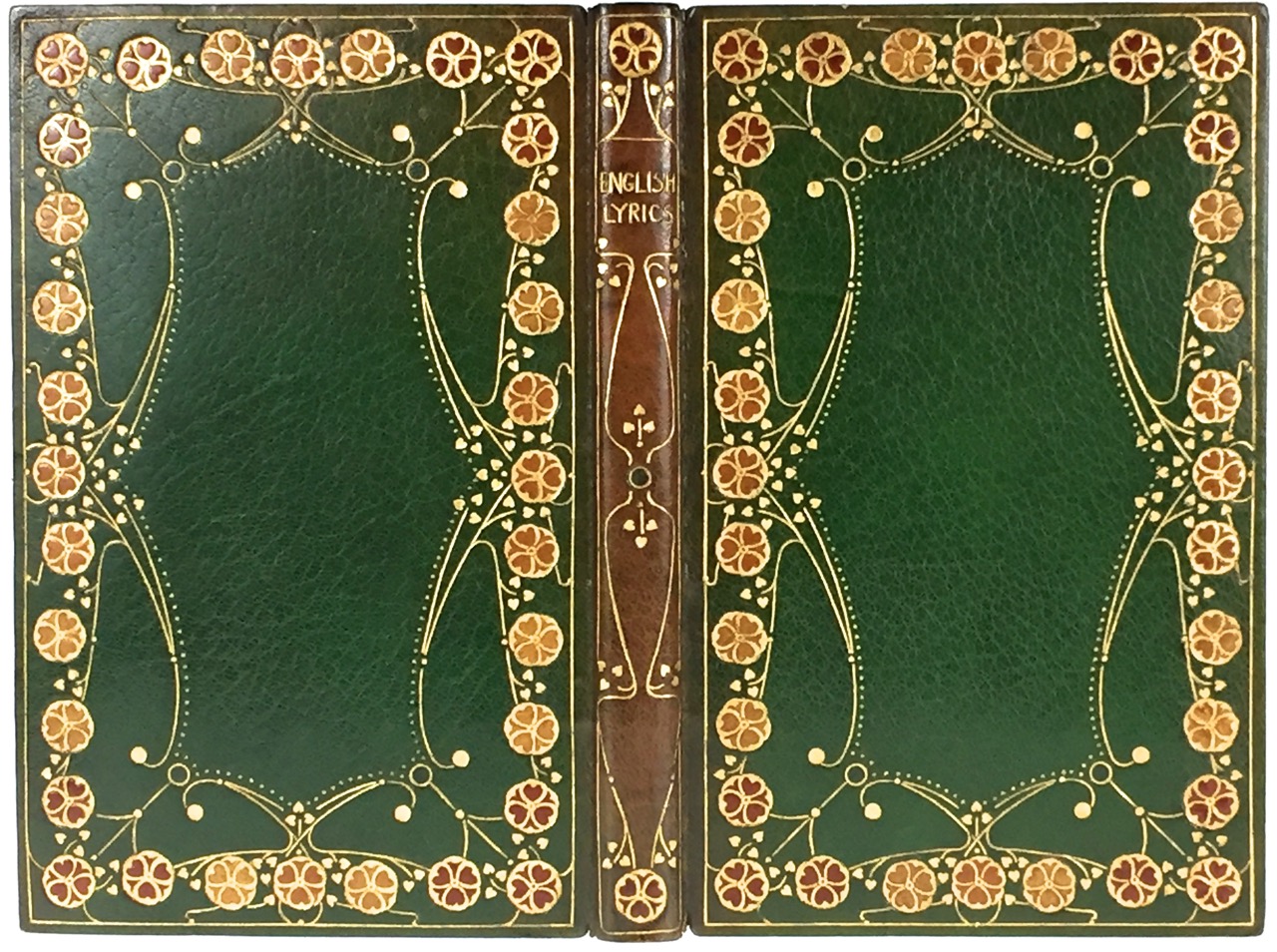

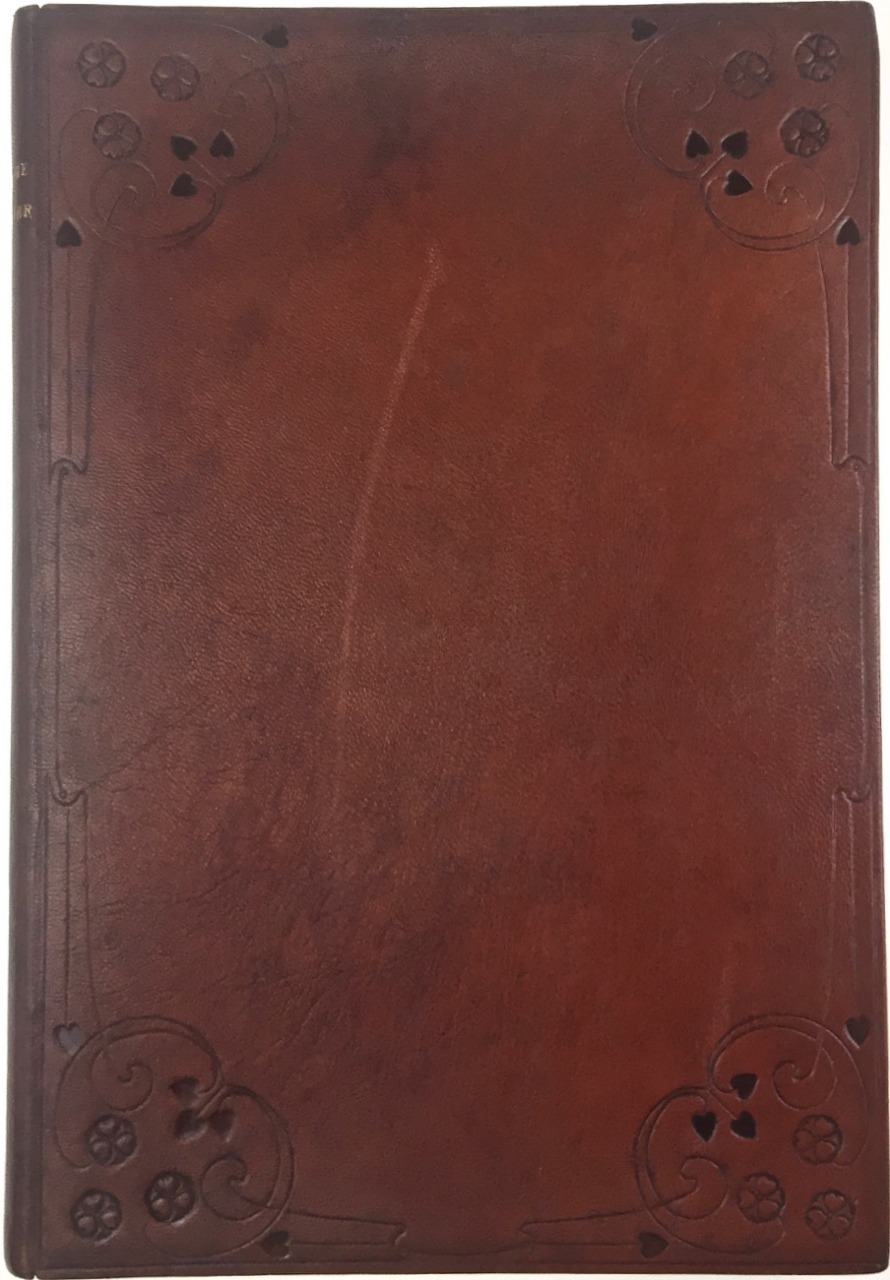

Left: Bindings by members of the Guild: English Lyrics from Spencer to Milton. Right: Cowper's Diverting History of John Gilpin. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

The model on which the Guild was based was well-established: founded on the Ruskinian principles developed by William Morris & Co and carried forward in organizations such as the Century Guild set up by A. H. Mackmurdo in 1882 and W. R. Lethaby’s Art Workers’ Guild of 1884, it promoted another version of the craft-based collective. It recalled the practices of Morris’s Kelmscott Press and it also anticipated May Morris’s venture in the field, the Women’s Guild of Art (1907).

There was a political dimension too. Though Karslake was far from liberal in his social attitudes – believing only that females were good at handicraft – the Guild can be viewed in the context of fin-de siècle demands for female emancipation. It at least asserted the capabilities of the New Woman, insisting that women could equal or even surpass the capabilities of men in a particular field.

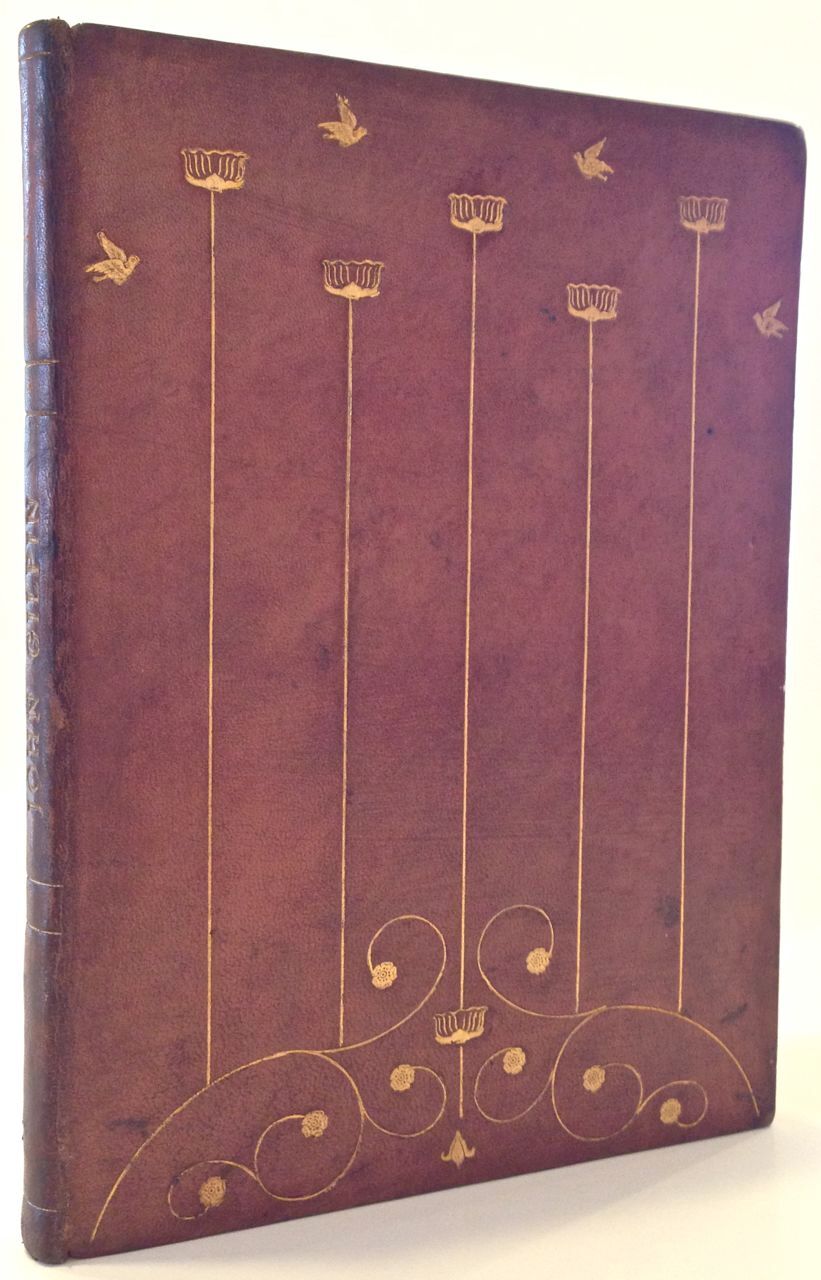

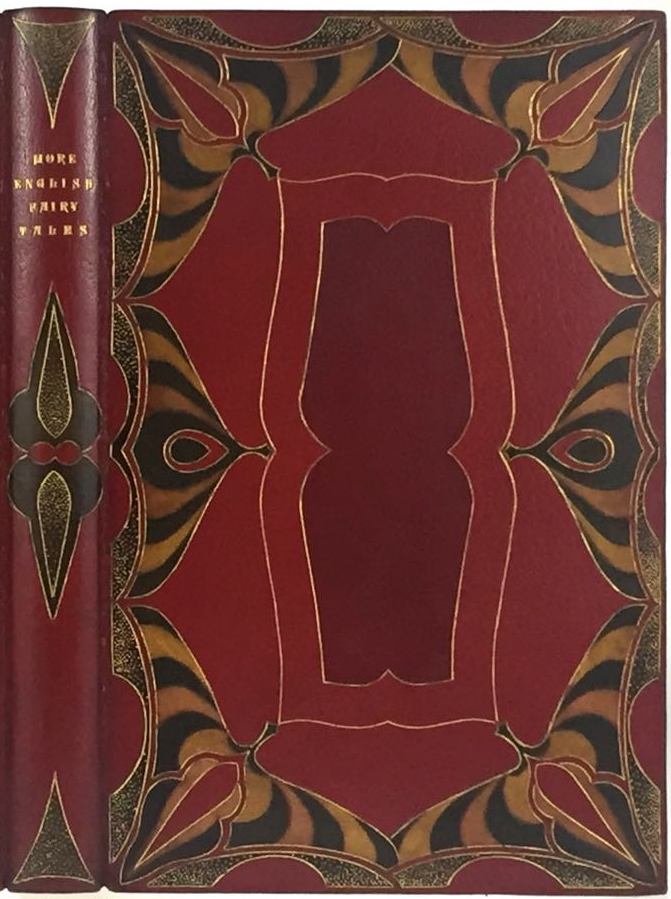

Three bindings by members of the Guild: Left: More English Fairy Tales by Helen Scholfield. Middle: Picturesque Westminster by Florence de Rheims. Right: Songs of Night and Day by Constance Karslake. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

The Guild was in this sense a female re-interpretation of the principles of Arts and Crafts. The application of these ideals is explained in some detail in by G. Elliot Anstruther in the only contemporary account of the movement. According to Anstruther, the Guild’s primary aims, like those of all of the other groups, was to assert the value of ‘handwork’ (xiv) by promoting the ‘self-reliant, consciously-proud figure of the English craftsman’ [sic] (vii). Intended to counter the impact of mechanization, the Women’s Guild was yet another attempt to raise the status of the maker and reinfuse the product with the crafts-person’s intelligence and personality: as Anstruther explains, it is only the self-confident creator who produces work of ‘individuality’ (xvii), ‘weaving the affections of the worker into the work itself’ (xiv).

In this version of making, the craftsperson becomes the author of the work rather than a technician: artisan becomes artist, and the two functions – designing and making – fuse into one. ‘The binder’, Anstruther continues, ‘should be the designer; the same hand that stitches the sheets and makes the cover [should create] the decoration and work the design upon the leather’ (xiii).

The integrity of the maker is matched, in the usual manner of the idiom, by the integrity of the material, which in the case of the Guild always involved the highest quality leathers, and by the careful pursuit of an organic wholeness, Anstruther outlines a credo of four considerations: 1: that the cover should possess ‘harmony of colour and form’; 2: that there should be appropriateness of ‘material treatment’; 3: regard for ‘exclusiveness’ or individuality’; and 4: a ‘correspondence’ between the binding and the ‘subject matter of the book’ (xviii). These criteria focus in a cryptic form the ideals pursued by Morris and T. J. Cobden-Sanderson, but it is also a gloss on all Arts and Crafts practice in the field of book-design.

Such principles are undoubtedly carried forward in the books designed by the Guild. However, the anachronistic nature of Karslake’s company almost certainly condemned it to failure. The bookseller may have wanted to improve standards and assert the value of fine artefacts in an age of mass-production, but he also wanted to make money to supplement and expand his book-selling; always intended as a ‘business institution’ (Anstruther, xiv), the Guild’s exclusivity and high prices generated few profits. Any chance of success was further undermined by a scandal, one of many in the bookseller’s slightly dubious dealings with businesses and business partners. On this occasion, fellow binders questioned the quality of the work, asserting that it was too good to be produced by trainees, suspecting that bindings were really produced at the Hampstead Bindery – another of Karslake’s interests – and insisting that the covers were beyond the capabilities of women. Sales suffered and trust was undermined; though intended to promote the best of handicraft, the venture was ultimately destroyed by ingrained social attitudes combined with unreasonable demands on the part of the proprietor, whose expectations were unrealistic. Anstruther claims that the Guild was at ‘the forefront of the revival’ in artistic bindings, and anticipated the ‘promise of a rich futurity’ (xxxi), but this optimism was ill-placed. The Guild finally closed in 1904, leaving behind a legacy of extraordinary quality.

Styles and Materials

The Guild only worked in fine leathers including morocco, calf and vellum. Each book was presented as a luxurious item, with closely-worked tooling and on some occasions inlays in a range of colours; many books had elaborate gilt patterns. The effect calculatedly recalls the elaborate bindings of the medieval and Renaissance periods; as in Morris’s productions at the Kelmscott Press, the aim was to break free of the mechanized production of the mid and later years of the nineteenth century and re-assert the material integrity of the Book as Art. Constance Karslake’s design for Frank Gunsaulus’s Songs of Night and Day (1896), though produced slightly before the inception of the Guild (1898), is a prime example of this type of self-conscious preciousness, and the same is true of the anonymous work for English Lyrics from Spencer to Milton (1898). Exquisitely crafted, both books are fine artefacts, with little thought for utility or practicality.

The emphasis on ‘individuality’ and ‘exclusiveness’ (Anstruther, xvii) meant that each binding ‘possesses a character of its own’, with each book being (at least theoretically) ‘distinguished by special treatment from all its fellows’ (xvii). There was, in other words, no obviously distinguishing aspect of style beyond the stringent insistence on fine effects. It is possible, nevertheless, to identify the impact of contemporary idioms. The congested surfaces of the Crafts aesthetic is abundantly in evidence, although many of the covers are characterized by the sinuous patterns and simplifications of Art Nouveau. The binding by Florence de Rheims for Picturesque Westminster (1902) exemplifies the bold linearity of the turn of the century; the delicate placing of heart-shapes recalls the design of C. R. Mackintosh and links to other luxurious book-covers by Charles Ricketts, notably his Poems, Lyrical and Dramatic (1893) and the recurring patterns in the same designer’s Silverpoints(1893). A Guild binding for Cowper’s Diverting History of John Gilpin (1899) similarly deploys Art Nouveau motifs, presenting a spare and elegant pattern to austere effect.

Though not innovative in terms of design, these and other books by the Guild are unique objects which stand in sharp opposition to the trade bindings of the period. They also add another dimension to the handicraft traditions of Morris and Cobden-Sanderson.

Acknowledgement

Special thanks are due to Mr Ed Nudelman, antiquarian bookseller, who has kindly granted permission to reproduce images of books by the Guild of Women Binders along with scans of other fine leather bindings of the period.

List of Binders

[*** = clicking on this name will take you to an example of this artist’s work. Further details of individual designers are given in Marianne Tidcombe’s recent study, Women Bookbinders 1880–1920.

- Ella Bailey

- Hélène Cox

- Mary Downing

- Muriel Driffield

- Gwladys Edwards

- Gertrude Giles

- Dorothy Holmes

- Constance Karslake***

- Olive Karslake

- Frances Knight

- Lilian Overton

- Annie Macdonald

- Florence de Rheims***

- Edith de Rheims

- Helen Schofield***

- Edith Slater

- H. W. Sym

- Gertrude Stiles

Related material

Works Cited and Consulted

Anstruther, G. Elliot. The Bindings of Tomorrow: A Record of the Work of the Guild of Women Binders and the Hampstead Bindery. London: Printed for the Guild of Women Binders, 1902.

Tidcombe, Marianne. Women Bookbinders 1880–1920. Newcastle, Delaware: Oak Knoll Press, 1996.

Last modified 24 January 2018