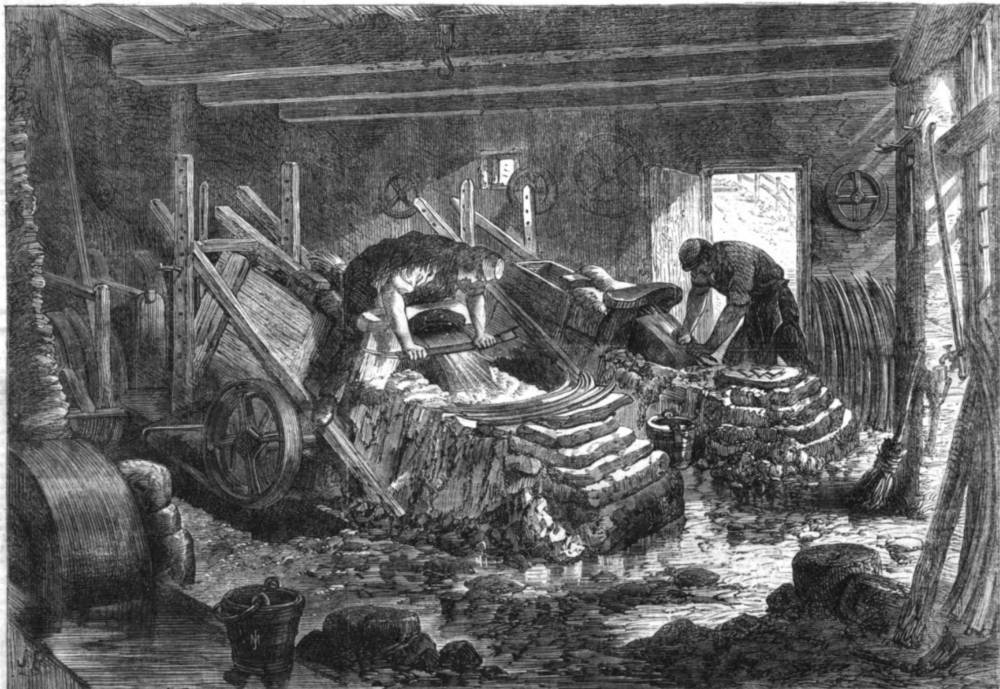

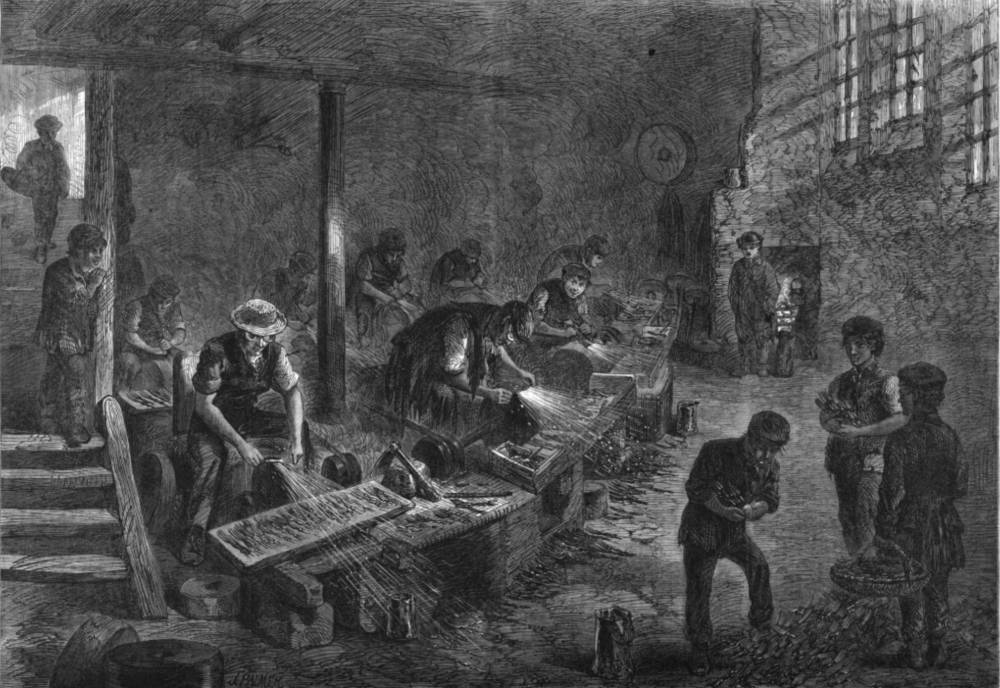

Scythe-grinding. Source: 1866 Illustrated London News. Click on images to enlarge them.

In the text that accompanied the illustrations in the multi-part article variously entitled “The Trades of Sheffield” and “The Manufactures of Sheffield,” The Illustrated London News draws upon the work of a local physician’s report on diseases caused by pollution and poisoning in a number of related industries. We have here a combination of several pioneering fields — epidemiology, ecology, and public health — for as Dr. Hall explains, the processes of producing edged tools shortened workers lives by a twenty-five years as they breathed metal and other particles. Workers involved in creating hand-made files — they were apparently superior to machine-made ones — were doubly in peril, since they encountered both metal particles from filing and also the additional danger of lead poisoning from other parts of the manufacturing process. Hall reports that both factory owners and workers contributed to this public health nightmare. Some factory owners failed to install the exhaust fans that greatly alleviated the air-borne pollution, and many workers, even though well aware of the dangers of breathing metal particles, refused to wear handkerchiefs or other means of protecting themselves from the dust while file makers at danger from lead poisoning didn't bother to wash their hands and protect themselves from lead while eating. — George P. Landow

In these articles The Illustrated London News, which devoted a great deal attention all kinds of modern technology, especially railways, bridges, and tunneling, here calls attention to its particular dangers.

I. Selections from the three-part article that accompanied the engravings: Introduction

“The Trades of Sheffield as Influencing Life and Health, more particularly File-cutters and Grinders,” was the title of a paper read or Dr. John Charles Hall, the senior physician to the Sheffield Public Hospital, before the National Association for the Promotion of Social Science during its recent visit to Sheffield. The important facts set forth by the writer have greatly interested all classes, and it is to be hoped that the result of Dr. Hall's labours will be the early interference by the Legislature to prevent a state of things which at present undoubtedly hurry many of the industrious artisans in those trades to a premature grave. We have sent our Artist specially to Sheffield to illustrate some of the more important proceases of the Sheffield trades described in Dr. Hall’s paper, and we are happy to have the Doctor’s authority for saying that “they most accurarately exhibit the several processes of wet and dry grinding and file-cutting.” Two only of the Illustrations are given in the present Number, and they refer to the comparatively healthy employments of saw-grinding and scythe-grinding, as practised in the neighbourhood of Sheffield. Upon this subject we will quote Dr. Hall. He observes that “men who work in the country, as a rule, are more healthy than those who grind at the wheels in the town, and as a body they are more temperate. One of the most healthy branches is saw-grinding. Many raws are ground at the water-wheels on the picturesque streams around Sheffield; and, as a rule, the men have not to work so many hours a day as at some of the other branches. Again, the trade is too heavy to admit of boys coming into it at a very early age. No boy is recognised by the Saw Grinders’ Union under the age of fourteen. The men stand at their work, and consequently the lungs are not so compressed as when the grinder, sitting on his horsing, bends forward for many hours each day in other branches of the trade about to be described. Scythe-grinding is also a healthy branch of the trade.” In contrast with these examples, we shall present hereafter a few instances of the less favourable kinds of work in the Sheffield steel manufactures, with the accompanying extracts from Dr. Ball's descriptive commentary on theit peculiar sanitary evils.

Left: The steel manufactures of Sheffield: The ‘Hull,’ or workshop, of the razor-grinders. With the use of the fan.. Right: File-cutting. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

II. Descriptions of grinding and the workplaces in which it is done — 20 January 1866

We have more than once called attention to the important revelations made by Dr. J. C. Hall, senior physician of the Sheffield Public Hospital and Dispensary, in his instructive paper read before the late Congress of the British Association for the Promotion of Social Science in that town, and we have announced the intention of publishing a few Illustrations, from sketches by our own Artist, of the manner in which the workmen employed there in various branches of steel manufacture are accustomed daily to pass their working hours. The commentary upon these arrangements, which are too often found so injurious to the health of the men, and which appears most urgently to demand official control and supervision, is supplied by extracts Dr. Hall’s printed treatise on the subject:—

“The rooms,” says Dr. Hall,

in which the grinders work at the various wheels are called hulls,” the literal meaning of which is a stye. In each room are placed a number of “trows” (troughs), more or less, in proportion to its length. Some rooms will have ten, some not more than two or three. The trough, which is made of cast metal, is received into the floor of the room, and contains the water in which the grinding-stone revolves. When the stone is run dry, the water is removed from the trough. Each trough has several divisions — one for the stone, one for the glazer, the lap, and the polisher. The glazer is a wooden wheel which varies in size from 4 in. to 4 ft. in diameter; it is covered with leather. This is “dressed” over with glue and emery, and when this application has set, the surface is rubbed with emery-cake, which is a composition of emery, suet, and beeswax. The lap is a wooden tool faced with lead, on which the aides of penknives, the sides of razors, and the flat sides of the better-finished scissors are rubbed to give them a flat surface. The polisher is placed at the back part of the hull. It is smaller in size than the wooden wheel already described. It is covered with leather, and mode to revolve much more slowly than either the grinding-stone or the glazer. If it revolved rapidly the blades either of the knives or razors that were undergoing the process of polishing would become heated, and the fine temper of the steel destroyed. Although the glazer revolves with no little rapidity the paste with which it is covered prevents this effect. A dry powder, called by the workmen ‘crocus’ (an oxide of iron), is used for polishing. Boys, who are apprenticed but too frequently to the lighter branches of the grinding trade at from nine to twelve years of age, are first put to polishing the different articles. I found a boy at work in a wheel last week, engaged in polishing, aged only seven. In my visits to wheels, I have frequently met with young bovs with coughs, shortness of breath, and lungs extensively diseased, who have never ground, but who have been injured by this process of polishing. In the back part of each room is a drum or wheel of large dimensions, which is set in motion bfr the steam-engine, and to it the grinding-stones, glazers. and polishers are attached by the ‘wheel-bands,’ which are broad leather straps. The connection between the different wheels and the drum can be effected or discontinued in n moment with the utmost facility by putting the bands on or off. Every drum ought to be protected by a rail. A large portion of the grinding-stones are brought from the neighbourhood of Wickereley and Dalton, a few miles from Sheffield.

Dr. Hall tells us that “to grind a razor to the proper shape great friction is required; razor backs are for the most part round, and the pressure during the sustain the rolling friction that the workmen are exposed to by far the greatest danger. The dust which is created by the stone and steel fills the room in considerable quantities, and when grinding scissors or forks two or three shaping is so great that no whetstone could ion.” Dr. Hall adds:

It is in dry grinding that the workmen are exposed to the greatest danger. The dust which is created by the stone and steel fills the room in considerable quantities, and when grinding scissors or forks two or three deep, without a fan, those who sit behind throw a large quantity of dust on those who sit in the front. But it is not only in grinding that dust ascends. Much of the evil resulting from the trade of a grinder, and this remark applies alike to dry and wet grinding, proceeds from ‘hacking’ and ‘’ the stones. The stones are received at the wheel from the quarry in a rough state. The grinder first drills a hole through the centre, and, fixing it on the axle, places it in the trough. It is then made to revolve slowly, in order that the steel which is used in the process of racing may bite. With this bar of steel the asperities of the stones are removed and their surface rendered level and smooth. During the operation, which frequently lasts half an hour, the rooms are unavoidably filled with dust; the dust also arises in dense clouds when the sides of the ‘trow’ are swept after the process of racing is over. It is easy to protect the nose and mouth with a light handkerchief during this process; but the precaution is seldom taken. On my asking a file-grinder at the Union Wheel a week or two ago, when collecting materials for this paper, and who I found racing a stone and covered with dust, why he was thus exposing himself to causes certain to induce a disease that would quickly bring him to a miserable death, he replied, “We know all about it, Doctor; but we never give it a thought.” Much dust also arises in glazing and polishing; the amount will depend in some measure on the nature of the glaze used. The glazing of forks is the most injurious. Almost all the grinding-stones are now fitted with plates and screws, instead of, as formerly, only with wedges: the number of accidents from the breaking of the grinding-stones are at present much less frequent than when the old plan was in operation. The saw-grinders at one time were often very seriously injured from the breaking of the stones when they were at work. The large size of the stones, and the weight and length of many of the saws they have to grind, will easily aooount for this branch of the trade being more dangerous, from the breaking of the stones, than when the articles are smaller and lighter.”

Dr. Hall thus describes the fan and the beneficial effects of it in the room sketched by our Artist, which was in the factory of Messrs. J. Rodgers and Sons: —

The fan is on the principle of a winnowing-machine, and with a flue properly constructed, leading from the different stones in each room, the dust can most effectually be driven out of it, and both the particles of grit and metal which arise in grinding, and the dust created in glazing and polishing, removed. I went last week into one of the rooms used for razor-grinding at the wheel of Messrs. J. Rodgers and Sons, where many men were at work shaping razors; there was no dust, nor was I inconvenienced in the slightest degree, during the half hour I remained. Had the fan not been at work, I know by experience that I should soon have felt most uncomfortable. One of the men told me the wheel had been “lame” for three works (i.e., not at work), and he had been working at another place without a fannie, and felt so bad at his chest that he was glad to get back to his own ‘trow’ again. He never felt bad there. At the Soho Wheel, and at the Umon Wheel also, and, I may add, at many other wheels, I have seen the fan at work with the happiest effects, and in the next room I have seen a set of reckless fools destroying themselves because they would not use it. Many yean ago, the late Mr. Trickett, at the Unidn Wheel, showed me how the different processes could be gone through without injury to the grinder from tne dust; and, at the Soho Wheel, I saw that shaping razors and even racing a stone, by adding a properly-contrived box could be rendered perfectly innocuous by the use of the fan, almost all the dust being driven off by the fan up a shaft on the outside of the building. The particles of dust and steel not carried away by the fan, in “racing” a stone, may be prevented from entering the air-passages by tying, as all intelligent grinders do, when performing this work, a light handkerchief over their noee and mouth.” [20 January]

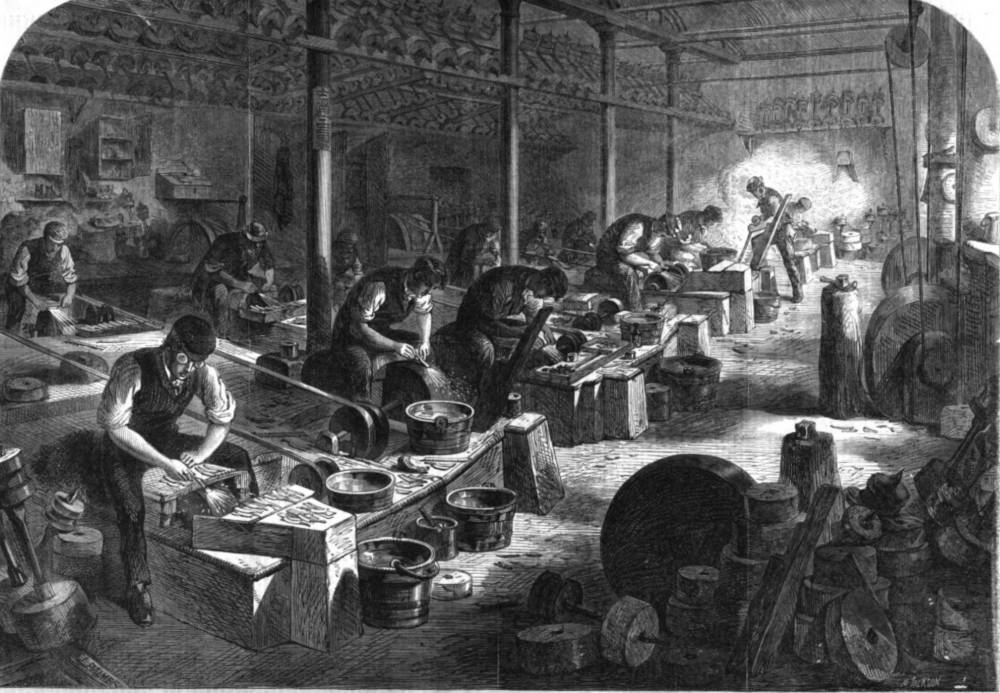

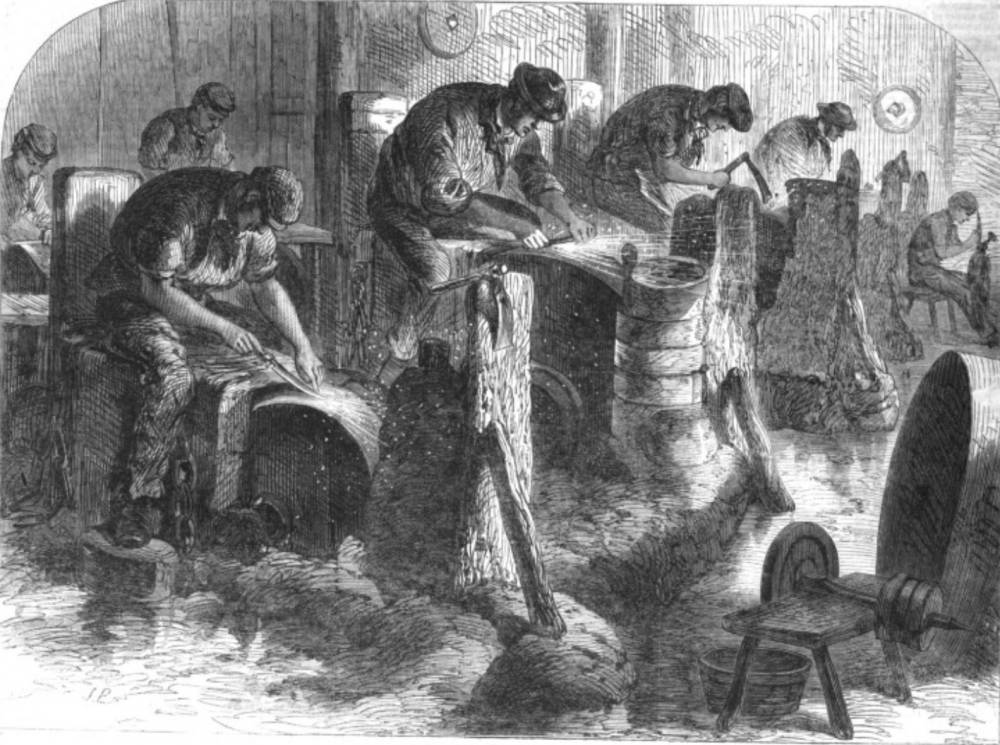

Left: The steel manufactures of Sheffield: Table-blade grinding. Right: Hull of the fork-grinders. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

III. Descriptions of grinding and the workplaces in which it is done — 10 March 1866

[This article repeats verbatim some of the descriptions and definitions of the previous one.]

In the Numbers of this Journal for Jan. 6 and Jan. 20 we gave some Illustrations, from sketches by our own Artist, of the interior of the workshops at Sheffield, in which certain operations of the steel manufacture are performed. The defective sanitary arrangements in most of these establishments, and the deleterious character of some parts of the work itself, were fully exposed by the last Report of the Children’s Employment Commission; and again, more recently, by the statements of Dr. J. C. Hall, the senior physician to the Sheffield Public Hospital and Dispensary, read before the National Social Science Association at their Sheffield meeting. We have already referred to Dr. Hall’s paper, and have extracted some passages, 1 describing the “hull” or workshop, of the razor-grinder, which was the subject of one of our Engravings. The processes of fork-grinding and table-knife grinding are shown in two of the present Illustrations; and we shall borrow Dr. Hall’s account of them:—

Grinders are divided into three classes: — 1. Dry grinders, using only the dry stone; 2. Mixed, or those who partly grind on the wet, and partly on the dry, stone; 3. Wet Grinders. Tbe grinder carries on his work in a building called a wheel. There are about 164 wheels in and near Sheffield: of these 132 are steam and thirty-two waterwheels. In each wheel are a number of rooms, which vary in size and the number of grindstones they contain. Here the grinders work. As a general rule, wet grinding and the heavier branches of the trade are carried on down stairs, and the lighter branches in the rooms on the upper stories. There are, however, many exceptions to this rule; and it is not uncommon to see wet and dry grinders working in the same room. The heavier branches of grinding include saws, scythes, table-knives, machine-knives, edge-tools, and files. The lighter branches are spring-knives (pen and pocket knives), razors, scissors, forks, spindles, and needles. A considerable number of men are employed in grinding glass. Tin rooms in which the grinders work in the various wheels are called “hulls,” the literal meaning of which is a “stye.” In each room are placed a number of “trows” (troughs), more or less, in proportion to its length. Some rooms may have ten, some not more than two or three. The trough, which is made of cast metal, is sunk into the floor of the room and contains the water in which the grinding-stone revolves. When the stone is run dry, the water is removed from tbe trough. Each trough has several divisions—one for the stone, one for the glazer, the lap, and the polisher. The glazer is a wooden wheel, which varies in size from 4 in. to 4 ft. in diameter: it is covered with leather. This is ‘dressed’ over with glue and emery; and, when this application has set, the surface is nibbed with emery-cake, which is a composition of emery, suet, and bees’-wax. The lap is a wooden tool faced with lead, on which the sides of penknives, the sides of razors, and the fiat sides of the better-finished scissors are rubbed to give them a flat surface. The effect of this will at once be evident to any one who has a first-class Sheffield knife, on comparing the pen with the pocket blade, or a razor with a table-knife. Tbe polisher is placed at the back part of the hull. It is smaller in size than the wooden wheel already described. It is covered with leather, and made to revolve more slowly than either the grinding stone or the glazer. A dry powder, an oxide of iron, called by the workmen crocus, is used for polishing. Boys of nine to twelve years of age are employed in this work. I found a boy at work in a wheel last week, aged only seven; and I have frequently met with young boys with coughs, shortness of breath, and lungs extensively diseased, who have never ground, but who have been injured by this work of polishing. In the back part of each room is a drum or large wheel, set in motion by the steam-engine, and to this drum the grind-ing-stones, glazers, and polishers are attached, by broad leather straps.

It is in dry grinding that the workmen are exposed to by far the greatest danger. The dost which is created by tne stone and steel nils the room in considerable quantities, and when grinding scissore or forks two or three deep without a fan, those who sit behind throw a large quantity of dust on those who sit in the front. Forks, needles, brace bits, and spindles are ground entirely on the dry stone, and in addition, table-knife bolsters, shanks, shaping-razors, and the ronnded sides of scissors require the dry stone to be employed. Some trades never use the dry stone: for example, saws, files, sickles, table-knife blades, edge-tools, and scythes are only ground and glazed. There is also a numerous class of grinders who work for the most part on the wet stone, and who are employed in grinding engineers’ tools, engravers’ steel-plates, hammers, fenders, fire-irons, stove-grates, busks for stays, candlestick-bottoms, nippers, garden-shears, or hoops.

Fork-grinders work on a dry stone, and their calling is perhaps more destructive than any of the grinding trades. The present number of men employed is about 150. Personal inquiries at the various wheels induce me to conclude the present condition of these men is no better than when a fork-grinder told me, some years ago, “I shall be thirty-six next month, and you know that is getting an old man at our trade;” and when I found the average age of the men only twenty-eight. Individual instances may be found of fork-grinders much older than this man; but it is, nevertheless, an undoubted fact that many fork-grinders miserably perish before the age of thirty. Take, for example, a boy of ten (and at that early age many of them go into the wheel); at the age of twenty-one his expectation of life, supposing he continue to work at his trade without a fan, would certainly not exceed fourteen years. Now, at twenty-one the probable expectation of life is thirty-nine years; so we see that these unfortunate men are exposed to influences which rob them of twenty-five years of existence—to that extent deprive their wives and families of the benefit of their labour, and fill the union poor houses with widows and fatherless children. There is no more melancholy object than a fork grinder, looking prematurely old and dying from the dust inhaled in his trade; no object more deserving of our pity, as we see him often crawling to his hull to labour, when altogether unfitted by the grinders’ disease for his calling: “his poverty and not his will consents.” In this condition, a day or two in a week, he grinds for a few hours; inhales additional dust; and, in order to obtain bread, increases the disease which already is rapidly destroying him. When at work, the grinder mounts what he calls his “horsing.” This is a low, narrow wooden seat. His elbows rest upon his knees, and his head, particularly when employed on very small articles, is bent over the stone. This position is a very injurious one, and when long continued is calculated, unquestionably, to induce pulmonary congestion.

Table-blade grinders are not so numerous as they were a few years ago, as many of them have gone to America, and few boys have been apprenticed, on account of the low prices that are now paid. The whole number is reckoned at 660 men and 170 boys. The number engaged in spring-knife grinding is 650 men and 200 boys. In all the branches together there are 3095 men and 1073 boys, or a total of 4163 men and boys engaged in grinding, dry, wet, and mixed. I have tested the accuracy of my return sufficiently to say that the average age of all the fork grinders does not exceed twenty-nine; scissors grinders, thirty-two; edge-tool and wool-shear grinders, thirty-three; table-knife grinders, thirty-five; the average age of the razor grinders has already been given. I regret to say that there is but too much truth in the remark once made to me by a young man of twenty-six, a fork grinder— he reckoned in about two more years at his trade he might begin to think of dropping off the perch, adding, “you know a fork grinder is an old cock at thirty.” On taking down the ages of all the grinders, wet, mixed, and dry, at one of our largest wheels, I found the average thirty-four; boys under twenty-one were excluded from this calculation. There can be no difference now; all the same adverse influences are still in operation, and sickness and premature deaths will continue until the causes producing them are removed.

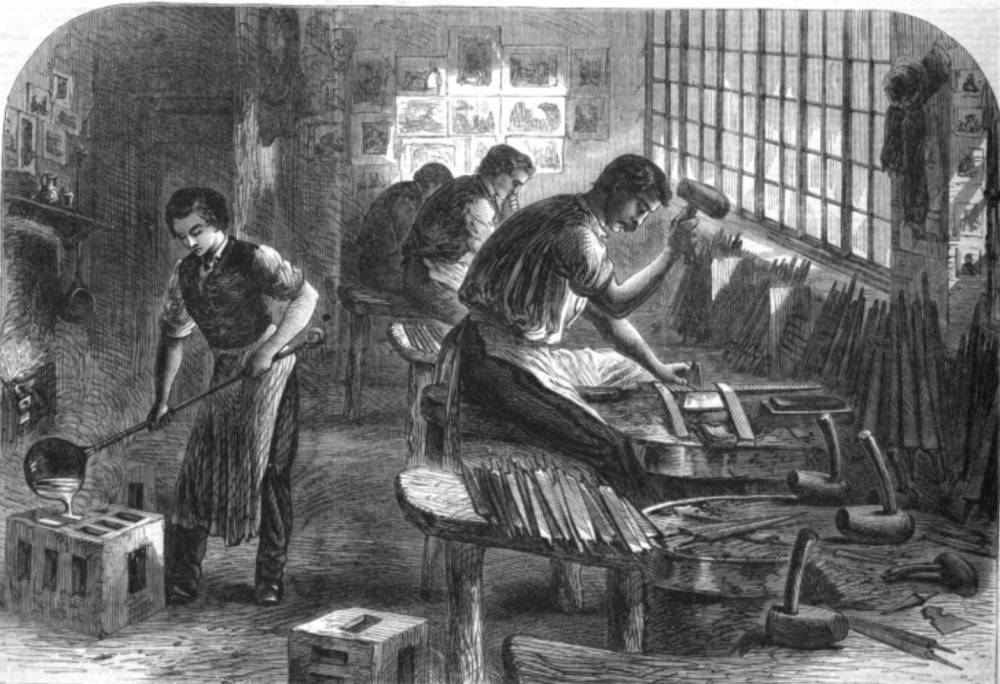

“The filecutters’ disease is poisoning by lead. Files are not cut by the machine in Sheffield, as machine-cut files are considered very inferior to those cut by hand. A file with 1000 cuts on each side is made with a hammer and chisel, and a man working ten hours can do about twenty such files in a day. The cutter uses a leather stirrup, which is for the purpose of holding the file upon an anvil inclosed in a stone stock. The file while being cut rests upon a bed of lead, and where many are cutting in the same shop fine particles of lead dust abound. In cutting files it is the custom of the men to wet the thumb and finger of the left hand by putting them to the mouth and so moistening them with their saliva. At every shifting, and when the file has to be turned, the lead is handled, and thus in a variety of ways it is absorbed into the system. The men eat their meals without washing their hands, and often take dinner in the workshop where the files are cut; as though fine lead-dust, handling the lead at each shifting, and licking the fingers were not sufficiently poisonous! I saw in one of the filecutters shops during the last few weeks a man, whose wife had just brought him his dinner, eating it with unwashed hands, and dipping his fingers, blackened and covered with fine lead-dust, into a paper which contained the salt for seasoning his beef."

It is evident from these circumstances that the workmen, as well as their employers, have much to learn, and that the diseases they suffer might often be prevented by better care. But this remark does not apply to those employed in dry grinding. The use of the “fan,” to carry off the dust, should be made compulsory. An Illustration of this contrivance, as used in the establishment of Messrs. J. Rodgers and Sons, has been given. [10 March]

You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the Hathi Trust Digital Library and The University of Michigan Library and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.

Bibliography

“The Trades of Sheffield.” Illustrated London News. 48 (5 January, 20 January, 10 March 1866): 17-18, 56, 70, 75, 238, 244. Hathi Trust Digital Library version of a copy in the University of Michigan Library. Web. 25 December 2015.

Last modified 25 December 2015