Mr. J. L. Pearson's name has been already mentioned among the

. . . group of contemporary architects, whose works have been conspicuous in the [Gothic] Revival, and perhaps there are none which illustrate so

accurately as his own, both in domestic .and ecclesiastical architecture,

its progress and the various influences to which it has been subject,

from the days of Pugin down to the present time. Mr. Pearson, like

many of his fellow students, began his professional career with the

fixed intention of adhering not only to the principles of Mediaeval art

but to national characteristics of style. His early churches in Yorkshire and other parts of England, many of which were erected between

1840 and 1850, exhibit those characteristics in an eminent degree.

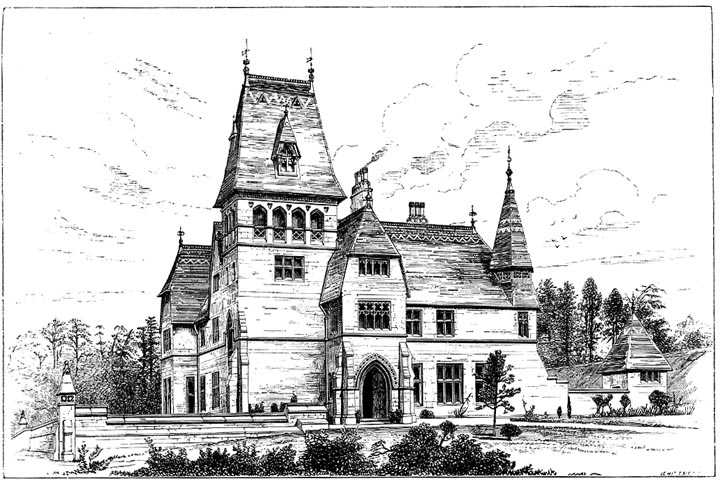

Treberfydd House in South Wales, which he designed for Mr. Robert

Raikes, is thoroughly English in its leading features and general composition. The plain but well-proportioned mullioned windows, the

modest gables, outlined by thin coping stones (the early Revivalists

made them of clumsy thickness), the battlemented entrance porch and

clustered chimney shafts, all indicate an attention to details then rarely

given, and though the architect was at first limited to the alteration of

an existing house, which must have considerably taxed his abilities, this

accident led to a picturesque treatment of the design, which no artist

would regret. — Charles L. Eastlake, A History of the Gothic Revival, pp. 302-303

Mr. J. L. Pearson's name has been already mentioned among the

. . . group of contemporary architects, whose works have been conspicuous in the [Gothic] Revival, and perhaps there are none which illustrate so

accurately as his own, both in domestic .and ecclesiastical architecture,

its progress and the various influences to which it has been subject,

from the days of Pugin down to the present time. Mr. Pearson, like

many of his fellow students, began his professional career with the

fixed intention of adhering not only to the principles of Mediaeval art

but to national characteristics of style. His early churches in Yorkshire and other parts of England, many of which were erected between

1840 and 1850, exhibit those characteristics in an eminent degree.

Treberfydd House in South Wales, which he designed for Mr. Robert

Raikes, is thoroughly English in its leading features and general composition. The plain but well-proportioned mullioned windows, the

modest gables, outlined by thin coping stones (the early Revivalists

made them of clumsy thickness), the battlemented entrance porch and

clustered chimney shafts, all indicate an attention to details then rarely

given, and though the architect was at first limited to the alteration of

an existing house, which must have considerably taxed his abilities, this

accident led to a picturesque treatment of the design, which no artist

would regret. — Charles L. Eastlake, A History of the Gothic Revival, pp. 302-303

In a more recent work, Roger Dixon and Stefan Muthesius characterize the architect's major churches, such as St Augustine's, Kilburn, St Michael's at Croydon, Surrey, and Truro, Cathedral:

They all show restful horizontals, continuous rooflines, sharp contours, square sections, undisturbed rectangular profiles. Pearson very rarely employs diagonally placed buttresses and uses little in the way of battering or tapering. But the overall emphasis is on the vertical, not on the horizontal or on the gradual building up of masses . . . To begin with, Pearson likes to surround the main body of his churches with a variety of small buildings, narrow aisles and chapels. Their purpose is to emphasize by contrast the size and height of the main parts. He usually intended a tall tower, though funds were not always available to build it. In its design he stresses the square contour, and keeps the enrichments at the top within this square outline, as was often the case in the Early Gothic of Normandy. Between tower and spire is a fairly thin cornice. Pearson's horizontals are always decisively drawn, but he never uses bulky string-courses or projections as does Scott. The spire, neatly fitted on to the tower, is sharply pointed but still fairly solid-looking, usually built of stone, and with relatively simple corner pinnacles. The main subsidiary vertical accents are the massive corner piers which flank the chancel and the west end of the nave — occasionally (as at Kilburn and Truro) curiously hemming in the west and east windows. Pearson's windows also reflect his concern for verticality: they are almost all elongated lancets. [219-20]

Like so many architects, Pearson took his son (and only child) into partnership with him, the partnership being formalised in 1890. Frank Loughborough Pearson (1864-1947) completed his father's magnum opus, Truro Cathedral, and other work in progress after his father's sudden death, and in subsequent years was responsible for further works of his own.

Works by J.L. Pearson

- Quar Wood, Gloucestershire (1847)

- Church of St. Peter, Vauxhall (1863)

- Chapel, Ta'Braxia Cemetery (also known as Pietá Military Cemetery), Malta

- All Hallows Barking, London EC3

- Truro Cathedral

- Two Temple Place, London WC2

- Pulpit, Truro Cathedral

- Reredos, Truro Cathedral

- Church of St James, Weybridge, Surrey

- Church of St Peter, Hersham, Surrey

- Church of St Augustine, Kilburn, London NW6

- St Edith's Church, Bishop Wilton, East Riding of Yorkshire

Works by Frank L. Pearson

Bibliography

Dixon, Roger, and Stefan Muthesius. Victorian Architecture. 2nd ed. London: Thames & Hudson, 1985.

Eastlake, Charles L. A History of the Gothic Revival. London: Longmans, Green; N.Y. Scribner, Welford, 1972. Facing p. 261. [Copy in Brown University's Rockefeller Library]

Hitchcock, Henry-Russell. Architecture: Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. 4th ed. Baltimore: Penguin Books, 1971.

Last modified 16 October 2025