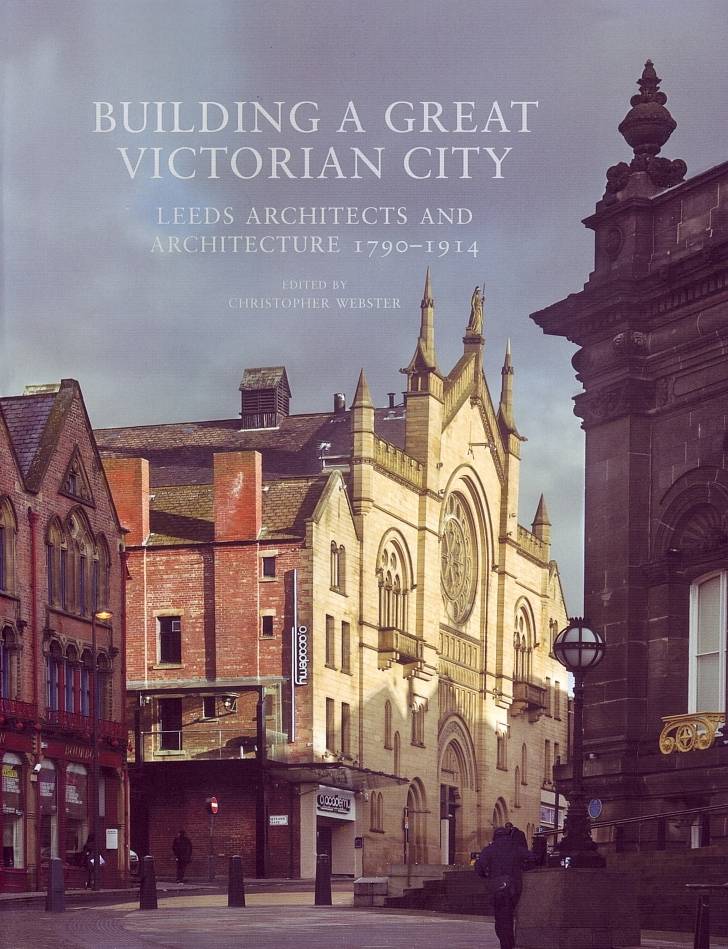

Cover of the book under review, showing (l. to r.) a pair of shops by Cuthbert Brodrick, and William Bakewell's Coliseum. [Click on the image to enlarge it. The following images are all from our own website. Click to enlarge these, too, and also to get more information about them.

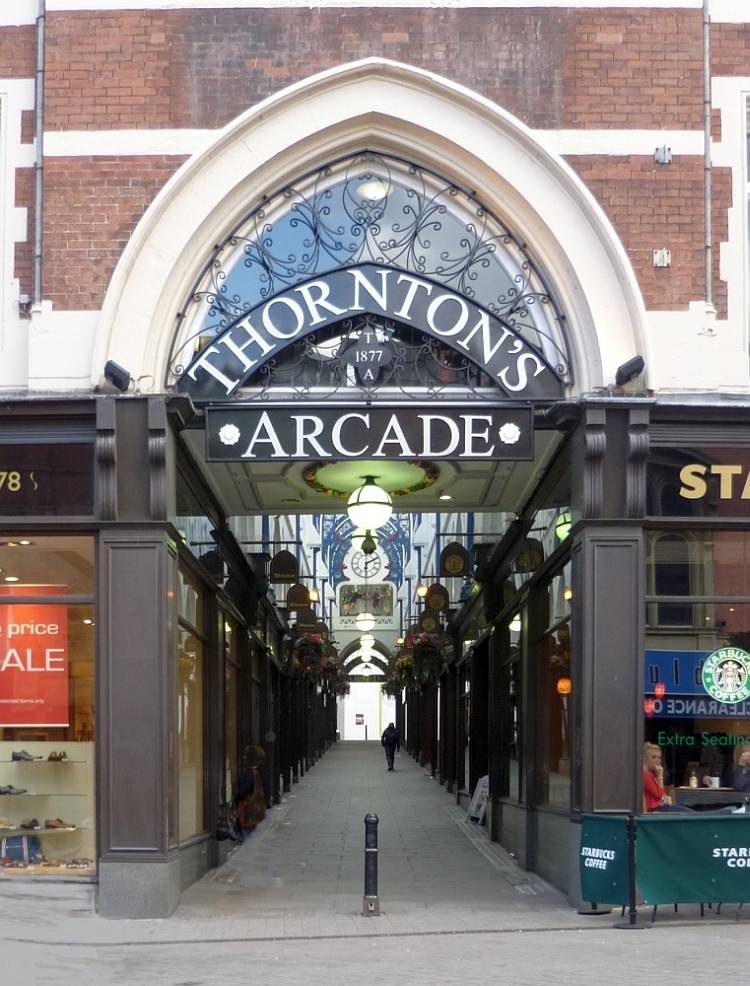

Some of the finest cityscapes in England are in Leeds. Briggate, the town's main shopping street, provides one of them. It may not have the neo-classical elegance of, say, Newcastle's Grey Street, but it has a naturalness and warmth about it, and an amazing skyline. Part of its warmth comes from the lingering presence of the past: originally the town's medieval market street, Briggate had a series of old narrow burgage plots leading up to the street front, and some of these were covered in Victorian times to make a series of handsomely fronted arcades, now equally handsomely restored. The first such arcade — the one that set the trend — was Thornton's Arcade (1877-78). This was by local architect and builder George Smith — sadly, not much seems to be known about him, though he was also responsible for the City Varieties Music Hall (1865) here.

Thornton's Arcade by George Smith, the first of several for which Leeds is famous.

Sometimes we know more about the architects involved. After all, some major London-based architects came from "up north." Alfred Waterhouse, for example, was born into a Liverpool family, and, having trained in Manchester, had his first successes there. He later provided Liverpool, Manchester and Leeds with their first purpose-built university buildings. Other architects, who spent the best part of their careers in the north, gravitated towards London later in life. Doncaster-born Henry Francis Lockwood (1811-1878) moved south only in his sixties, after having made a name for himself with Bradford Town Hall and other important work in the Bradford area. But provincial towns also had fine architects whose practices kept them busy at home throughout their working lives. Not being represented in the capital, they remain practically unknown there.

Finding out about them can be difficult. The Pevsner "Buildings of England" series and individual city guides are indispensable, but operate geographically. Extracting information about particular architects from introductory discussions and indexes is time-consuming. This collection of essays about Leeds, on the other hand, focuses on the architects themselves, giving us a highly satisfying mix of local, biographical and architectural history, and informed assessment. Kevin Grady's opening essay sets the scene by dealing with the transformation of Leeds from a medieval market town into an economic powerhouse, while another early essay, Christopher Webster's "The Architectural Profession in Leeds (1800-1850)," traces the general trend towards professionalisation. In both these ways, as Webster says in his preface, Leeds was a "microcosm of English architectural history in this period" (2) — though there is a canny Yorkshire feel about certain comments. For example, local folk gradually became more willing to employ a trained architect because it was simply "the best way to police the worst excesses of the building trades and protect the interests of the client" (78).

Left to right: (a) St Peter's, Kirkgate, by R. D. Chantrell. (b) Leeds Town Hall, by Cuthbert Brodrick. (c) The Corn Exchange, by Cuthbert Brodrick.

The first two architects to set up professional practices in Leeds were Thomas Johnson (1762-1814), and Thomas Taylor (1777/ 8-1826), both of whom had learnt their skills with James Wyatt in London. The former was almost certainly born in Leeds, but the essay on him raises more questions than it answers: "there is a paucity of documented work," admits Terry Friedman (44). The latter, probably born in London, was an early Gothicist responsible for some particularly fine churches, and is of more interest. So many church builders of this time were "pioneering" in this respect — though only one went about it as passionately and polemically as Pugin, or made such an impact. In Leeds, the most important of the new breed was Robert Dennis Chantrell (1793-1872), and Webster, in the third of his four essays in the collection, does him full justice, contextualising his rebuilding of St Peter, Kirkgate, while showing how it "lifted Chantrell's career to a new level" (109).

Cuthbert Brodrick (1821-1905), Thomas Ambler (1838-1920) and George Corson (1829-1910) are among the others to be discussed in individual essays. Brodrick, whose town hall and corn exchange are among the most iconic of provincial buildings, had trained under Lockwood in his Hull office, but turned down the offer of a partnership with him to strike out alone. Leeds Town Hall was his first major commission. Architectural historian Colin Cunningham has consulted extracts from the Clerk of Works' diary for the project, which reveal him to have been so exacting (and, surely, irascible) that on one occasion he smashed an unsatisfactory cornice stone with a hammer, to prevent it from being used (184). Probably the same bull-headedness that made him turn down Lockwood's partnership offer, and smash the cornice stone, made him willing to sacrifice his planned grand entry to the demands of the heavy tower on which he had set his heart: the tower, of course, needed "massive supporting piers" (185). Daringly innovative in using industrial-type roofing for his "municipal place" (187), Brodrick was perhaps weaker on the intricacies of design. Cunningham suggests that this was one reason why he stopped winning prestigious commissions.

St Paul's House, by Thomas Ambler.

Of special interest is the kind of work undertaken in these northern architects' offices. In the right hands, designs for breweries, mills, workshops, warehouses and factories could all reach new heights, perhaps the most striking example being Ambler's exotic St Paul's House, which, Janet Douglas tells us, once housed "two hundred sewing machines, cutting and pressing rooms, warehouse facilities and show rooms" (226). Susan Wrathmell has useful details about George Corson's work, too, especially about his extension of George Gilbert Scott's Leeds General Infirmary, his last major commission. This was more than a matching piece: it had an innovative out-patients' hall with "curved steel trusses springing from corbels" (254). Particularly fascinating is all the professional detail Wrathmell has uncovered in this essay. Corson's practice included or used an impressive array of assistants, pupils, site staff, engineers, craftsmen and artists. Drawings were signed off by "Thomas Coston, Emily E. Nicholson, Marshall Nicholson and Thomas Winn" (256). It is rare to see a woman's name mentioned in such a context.

Left to right: (a) The vast City Markets, by Leeming and Leeming. (b) The Victoria Quarter on Briggate, by Fank Matcham, with its dazzling faience. (c) The Oxford Place Methodist Chapel, by James Simpson, G. F. Danby and W. H. Thorp, facing Brodrick's Town Hall.

Already kitted out with one of the grandest town halls in the land, Leeds achieved city status in 1893. This further boosted the demand for statement-making public buildings, new churches and chapels, commercial premises and industrial buildings, as well as schools and housing. Sometimes local architects could still produce the goods: the grand City Markets were designed just after the turn of the century by the Halifax firm of John and Joseph Leeming (sadly, again, not discussed here). However, the big London architects began to make greater inroads. With Clerks of Works to supervise their projects, and railways to facilitate their own inspections of the sites, they could take on many far-flung projects at once. The last essay here is about the work of such architects, though inevitably it deals rather cursorily with them — just a paragraph on Frank Matcham, for instance, whose Victoria Quarter (a "swaggering design in faience," as Douglas aptly describes it, 318), gives Briggate its greatest impact. Nevertheless, Kenneth Powell's penultimate sentence says it all: "Despite the vitality of the local scene [at the end of the period], it was London that set the pace for new architecture in the city" (146).

Other local architects dealt with at some length are James Simpson, Chorley and Connon and their partners, Walter Samuel Braithwaite, Thomas and Charles Barker Howdill, the Bedford and Kitson practice, and Percy Robinson. All deserve their space for one reason or another, even the more middle-ranking Howdills, who built Methodist chapels as far away as Bristol and the Isle of Man. Finally, a "Directory" gives details about architects and firms not dealt with in the main essays. William Henry Thorp (1852-1944) has quite a long entry here, but it still seems a shame that he should not have been featured nore fully, and earlier. He remodelled the Oxford Place Methodist Chapel and Oxford Chambers, designed, amongst other landmark buildings, the town's new Art Gallery and the distinctive library and police station complex at Woodhouse Moor, and was generally very active in the architectural life of the city. The Builder described Thorp in its obituary of him as "one of the best known architects in the north of England" (410).

A smaller quibble: the essays and Directory are copiously illustrated in black and white, often with historic photographs. One picture, of W. W. Gwyther's "former Midland Bank," has a caption explaining that "[b]y the end of the century, many national companies had their own in-house, usually London-based architects" (172). Gwyther was indeed London-based, but he designed this building as the headquarters of the Yorkshire Banking Company, before it amalgamated with others to form the Midland. So he was working for a regional bank and hardly as its "in-house" architect. This is a very minor point, though. Building A Great Victorian City is a hugely informative book, and a pleasure to read. In giving new prominence to those who made Leeds so architecturally unique, it also serves as a fine memorial to Derek Linstrum and Colin Cunningham, two important architectural historians with a special interest in Leeds, who died in 2009 and 201 respectively, and to whose memory it is partly dedicated.

References

Webster, Christopher, ed. Building A Great Victorian City: Leeds Architects and Architecture 1790-1914. Paperback. Huddersfield: Northern Heritage Publications (an imprint of Jeremy Mills Publishing) in Association with the Victorian Society, 2011. 419 + x pp. with 330 illustrations. £30.00. ISBN 978-1-906600-64-8.

Last modified 16 March 2012