With thanks to Sue and Chris Bond for their infomation about the glazier. Chris also kindly contributed two photographs here (the view through the screen, and the very last). The rest are by the author, except for the one of the church interior, looking east. This is by Keith Laverack, originally posted on the Geograph website, and available for reuse under the Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-SA 2.0) licence. You may use the others too without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one. Click on the images for larger pictures.]

The church from the south-east.

St Catherine’s church, Barmby Moor, East Riding of Yorkshire, rebuilt by Robert Dennis Chantrell (1793-1872) in 1850-52. Barmby Moor village is two miles west of Pocklington and 12 miles east of York. By 1850, the medieval church was in a bad state, and it was decided, not without opposition, to build a new nave and chancel while retaining the medieval west tower. This was carried out "in Dec style but conservative for its date, i.e., not yet influenced by the Ecclesiologists" (Pevsner and Neave 271). Of particular interest here is the fact that the incumbent, the Rev. Robert Taylor, was married to Herbert Minton's sister Catherine. Chantrell's work with Minton tiles gave the church a uniquely impressive interior.

View from the nave looking east.

The Rev. Taylor had already employed Chantrell in 1849-50 to rebuild another church in his care, St Martin’s, Fangfoss. There, it had been possible to re-use much of the original Romanesque sculpture and build a "Norman" church, but there can have been very little ancient material worth saving at Barmby Moor. All that was kept is part of a late twelfth-century doorway probably from the chancel, but demoted to serve as the entrance to the boiler room.

These two works occupied Chantrell shortly after he had moved to London in 1847; he was at this time the consulting architect to the Incorporated Church Building Society for the diocese of York, and at the beginning of "a long semi-retirement as an eminent antiquary, scholar and something of an elder statesman of the profession" (Webster 99).

Windows with pointed arches

From left to right: (a) East window. (b) West window. (c) Window in chancel

The new church opened in 1852, as described in the Yorkshire Gazette. Its plan is an open rectangle with no defining chancel arch, merely two shallow steps up towards the east end. The large east and west windows, and the side windows in the chancel, have a pointed arch. The length of the nave as first conceived has recently been divided by a glazed screen separating the worship area from a western secular space or meeting room and useful offices: this is successful and does not interfere with the earlier work. A staircase to the choir vestry in the tower allows access to see the west window close-up.

Rectangular nave windows

Left: Vestry window. Right: Two windows from the nave.

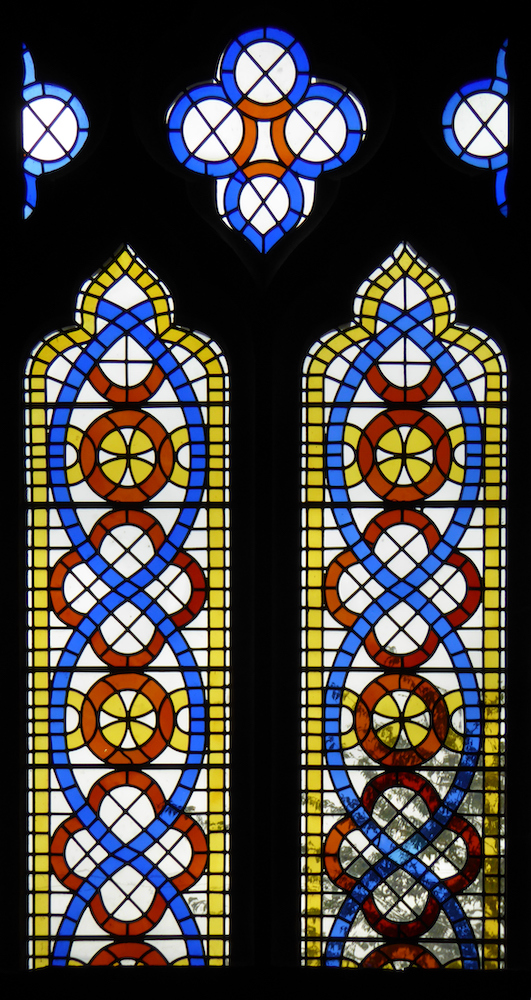

The style is indeed derived from the Decorated, with the windows in the nave being within rectangular frames. Outside, the pointed windows have crowned heads as label-stops, but nave windows have none. While a few of the side windows have since been replaced with pictorial memorials of one sort or another, those initially installed have coloured glass arranged in simple abstract linear patterns, all different; there very few even remotely symbolic forms. The windows seem to have been designed by Chantrell and were made by a Pocklington glazier named Richard Simpson Cook (1819-1853). In 1845, Easton’s Directory lists Richard Cook as plumber, painter and glazier, with premises in Finkle Street, Pocklington. No more of his glass has been traced, but it may be that he was chosen by Chantrell as a traditional craftsman who could produce something more honest than the plethora of ornament seen at the 1851 exhibition.

Transverse screen, and roof

Left: View from the balcony on the west side of the tower, across the meeting/entrance room, through the screen and looking east. Right: Roof, looking west.

The roof was also designed by Chantrell and it was made by another local craftsman, Thomas Beal of Pocklington. The simplicity of the interior at Fangfoss suggests there were limits to the funds that the careful Rev. Mr Taylor was willing to spend; this would have been another reason to use local craftsmen and not more famous firms from Leeds or London. The modern glazed screen can be seen dividing the nave worship area from the meeting room at the south door.

Tile scheme

From left to right: (a) Chancel tiles. (b) Looking along the front of the nave. (c) One of the blue tiles.

The tiles of the chancel are well-known, being mentioned by Nikolaus Pevsner and David Neave (271-72), and in Lynn Pearson’s Tile Gazetteer (375-76). The latter also mentions Minton tiles in the chancel at Fangfoss (376). Since 1852 major changes have been made to the interior arrangements and fittings, the chief of which was the moving of the organ from the west to the east end, first to the side wall and now to the centre, between the altar and the east window. No faculty papers for either the 1850-52 rebuilding or the reordering of the interior between 1980 and 2001 have been found, so it is impossible to know what the area of tiles in the chancel looked like originally, though there may be plans in the uncatalogued Pace and Sims archive in the Borthwick Institute, York. At present, the organ, altar and a paved platform occupy the centre, while altar rail and seating encircles them; these things conceal or cut up the design. All one can say is that the clear Minton blue was more used in the easternmost tiles in the central area, while the variety of detail outside that is maintained using more subdued earth colours in encaustic designs.

Memorial tiles and the royal arms

Left: To the Vicar's wife. Right: To Herbert Minton.

Later, commemorative tiles to the Vicar’s wife Catherine (Herbert Minton’s sister, died 1861) and to Herbert Minton himself (died 1858) were inserted. There is another decorative tile worthy of note. From the 17th century onwards, churches had often displayed a royal coat-of-arms to show loyalty to the reigning monarch as head of the church: this was normally painted on canvas or board, and usually square. Here that convention was followed by placing the royal arms in Minton tiles on the wall above the vestry door. In the pavement, however, the commemorative tiles recall the custom of showing the arms of a deceased person in a diamond-shaped hatchment. The royal arms are also placed diamond-wise so perhaps the significant difference – square or diamond, alive or dead – was being disregarded. There is a royal coat-of-arms very like this at Newark-on-Trent, in St Mary Magdalene’s church, at the west end of the nave in a floor laid by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott in 1853-5; that church has many commemorative tiles too (Pearson 277-78).

The joyfulness and modernity of Chantrell’s glass is striking, yet the glass is not mentioned by Pevsner and Neave, and "Victorian" glass saints and pictorial windows were still being installed here in 1936. On the other hand, Ronald Sims (1926-2007), the architect responsible for the reordering of the interior between 1980 and 2001, appreciated Chantrell’s glazing, as its lines clearly inspired the iron gates he designed for the churchyard; perhaps he associated the glass with the Arts and Crafts movement with which he was sympathetic. Yet unfortunately he disregarded the Minton tiles, perhaps associating them with the evils of mass-production, and well aware that there were thousands more elsewhere; the period in which Sims worked was still one which abhorred the Victorians and their typical products. It would have been interesting to see how the glass and the tiles had looked together in their first state. Would we think they harmonise, or clash? Love the one and hate the other? Perhaps a mid-Victorian would not have seen a problem: Chantrell must have known the tiles were arriving, he saw no discord, but an addition of glory to his church.

Related Material

- Encaustic tiles at St Catherine's, Barmby Moor (six more examples)

Bibliography

"Barmby Moor" (account of opening). Yorkshire Gazette. 17 April 1852: 7.

Pearson, Lynn. Tile Gazetteer: A Guide to British Tile and Architectural Ceramics Locations. Tiles and Architectural Ceramics Society, 2005.

Pevsner, Nikolaus, and David Neave. Yorkshire: York and the East Riding. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2002.

St Catherine’s church Barmby Moor: A Short History and Guide. c. 2014. Available at the church.

Webster, Christopher. "Robert Dennis Chantrell (1793-1872)." Building a Great Victorian City: Leeds Architects and Architecture. Huddersfield: Northern Heritage Publications in Association with the Victorian Society, 2011. 99-116.

Wood-Rees, W. D. History of Barmby Moor from prehistoric times. Pocklington: Private publ., 1911.

Created 2 September 2020