[Part 1 of A Gazetteer of Lock and Key Makers, which the author has kindly shared with readers of the Victorian Web. Readers who wish to check out the original site can find it by clicking here.]

Locksmiths from other parts of the country

There were, of course, locksmiths in other areas of England. For instance, Joseph Bramah, perhaps more famous for inventing the flushing w.c., was born in 1748 in Barnsley, Yorkshire, and became a cabinet maker in London. In 1788, along with Mr. Maudslay, he patented an extremely strong lock. In 1790, he displayed it in his London showroom window, with a notice attached:

The artist who can make an instrument that will pick or open this lock shall receive 200 guineas the moment it is produced.

Another Yorkshire locksmith was Thomas Milner, who was bound in 1791 as an apprentice to his father in the trade of tinsmith and brazier for eleven years. In those eleven years he was not to marry, take a drink or take a day off without permission. He was provided with meat, drink, washing, lodgings and wearing apparel. His wage was sixteen pence a year.

He learned well and began to manufacture iron coffers and strong boxes. In 1824 he secured orders for these from the Duke of Wellington as well as an official contract to supply the War Office. Thomas moved in 1830 from Sheffield to Liverpool and set up the firm of Thomas Milner and Son, where he was a pioneer in the development of fire resistant safes and much involved in taking out patents and demonstrating the excellence of his safes by placing them in the centre of huge bonfires.

Then there was Samuel Chatwood, who was younger than George Price, born in Liverpool in 1833. He became an agent for Simpsons Patent American Sewing Machines in 1859; but in March 1861 he announced he had engaged the services of William Dawes, Civil and Mechanical Engineer, who had previously managed the Coalbrookdale Ironworks in Shropshire, to begin manufacturing a range of one hundred and eleven safes.

The partnership lasted about eighteen months. William Dawes was headhunted by George Price in late 1862, becoming his Chief Engineer and very likely his brother-in-law. George's wife was Ann Dawes of Wrockwardine, Shropshire.

But Chubb is perhaps the must famous of all English lock companies. Charles Chubb came from Portsea, but his works were in Wolverhampton. In May 1832 Charles Chubb offered a prize of ’10 to Thomas Hart, an ingenious local locksmith, if he could pick his best lock at the New Hotel, Wolverhampton. It remained unpicked, although there was plenty of discussion about whether the challenge was fair or not.

George Price's early career

George Price was born in 1819, the same year as Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. He was the son of Joseph Price of Bilston, who was a local historian and printer who wrote "An Historical Account of Bilston from Alfred the Great to 1831" and "A Summary of Mr. Leigh's History of the Cholera in Bilston in 1832". His maternal grandfather was Joseph Pedley of Willenhall, an agent who exported ironware to America. George is listed at various times in local trades directories, from the age of twenty-one (1840) as a printer, an agent, an accountant, an auctioneer, a nurseryman, an insurance agent and debt collector.

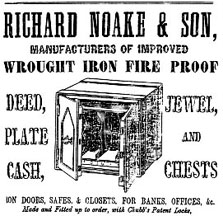

As an insurance agent he would have been aware of the financial rewards awaiting anyone who could produce reliable burglar-proof locks, safes and strongrooms which were also fire resistant. His father, as an historian and churchwarden, was always concerned that both fire and burglary threatened rare and precious documents and regalia. So George knew he was likely to be on to a winner when he took over, in the early 1850s, the works of Messrs. Richard Noakes and Son of Cleveland Street, Wolverhampton: "Manufacturers of improved wrought iron, fire-proof deed jewel, plate and cash chests -- made and fitted up to order, with Chubb's Patent Locks".

George was a true Victorian entrepreneur, a great believer in progress through scientific experiments. George Price's methods of production initially must have been very much the same as Noakes'. Safes were made fireproof by building them with cavity walls filled with powders and chemicals which would not burn, even if the safe was subjected to intense heat. Through perforations in the inner wall of the safe, when the non-combustibles became very hot, they gave off' steam which would keep the contents relatively cool.

The great lock controversy of 1851

George Price includes a substantial account of this controversy in his book. In the one hundred and fifty pages which are given to the "Great Lock Controversies" he tried to present fairly the points of view of all the combatants: Chubb, Bramah, Cotterill, Hobbs, the bankers and The Royal Society of Arts.

1851 was the year of the Great Exhibition in the Crystal Palace in Hyde Park, London. This exhibition was intended as a showcase for the most excellent products not just from Britain, but also from the whole world. Nothing was for sale -- in theory -- just for show.

However, the man who provoked the Great Lock Controversy, a very ingenious prize winning lock engineer from America called Alfred Hobbs, visited the Exhibition and insisted on buying a splendid exhibition lock trophy (shown right), made by Charles Aubin of Wolverhampton, (who was later to provide the locks for George Price's safes).

Then Hobbs put the cat amongst the pigeons by picking one of Chubb's best locks which was fitted onto a strong room in Great George Street, Westminster. It took him twenty five minutes.

He then moved on to Bramah's great lock which had been displayed, unpicked, in a London showroom window since 1790. Hobbs took up the challenge to pick it and succeeded, although it took him forty-four hours.

Bramah's lock -- interior of reverse side

He aroused panic amongst British bankers who believed these and similar locks to be perfectly safe. How could they be sure there were no bands of thieves just as skilled as Mr. Hobbs? The Times letter column exploded with letters from Chubbs and Cotterills of Birmingham, defending their locks and reassuring the bankers: "Which burglar would have forty-four uninterrupted hours to work on a lock?"

The bankers and insurance companies insisted that the Royal Society of Arts, which was an organisation which promoted high standards in industry, should offer a prize for a strong, secure and reasonably priced lock which could not be picked. The prize was given to a locksmith called Mr. Saxby. Ah, peace of mind at last!

But Hobbs picked it in three minutes. George Price's view was that it was better that an honourable man should pick it than a thief and it was only through such challenges that Progress was possible.

Last modified: 6 February 2003