The Maiwand Lion. George Blackall Simonds. 1866. Bronze. 31 feet. Forbury Gardens, Reading. Click on images to enlarge them.

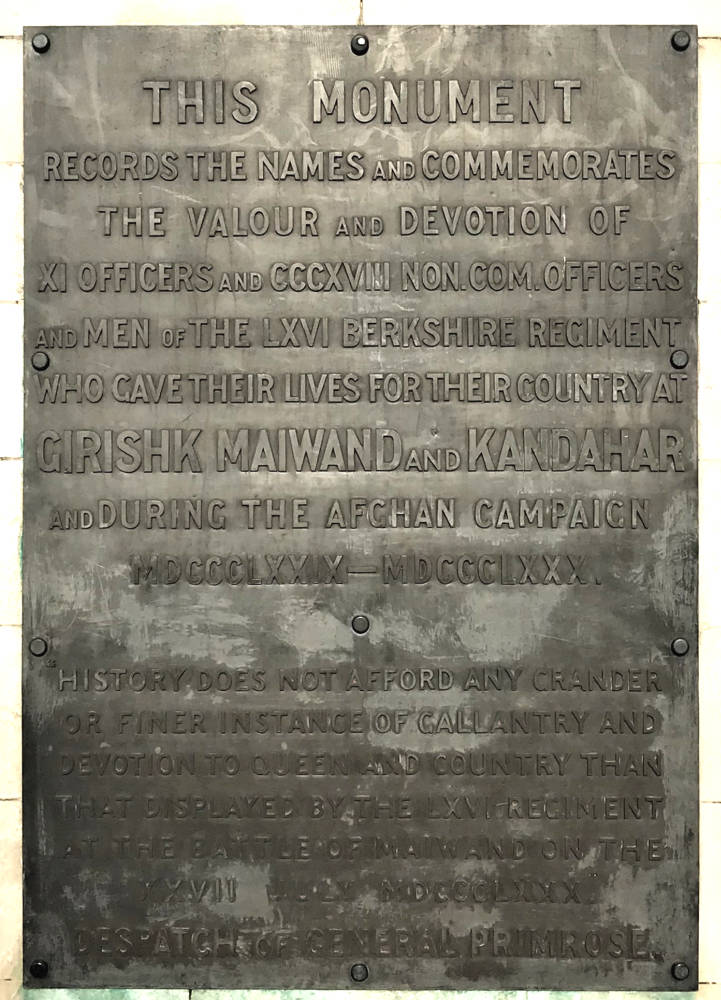

25 minutes by train to the West of London lies the town of Reading. Close to the station is Forbury Gardens which is dominated by a vast cast-bronze lion known as the Maiwand Lion. This commemorates the deaths of 11 officers and 318 men of the 66th (Berkshire) Regiment in the Second Afghan War. The majority (286) died in the disastrous battle of Maiwand near Kandahar on 27th July 1880. It is probably the finest memorial to Britain’s Afghan wars apart from the Afghan Church in Bombay (now Mumbai).

The 31-foot war memorial in the Forbury Gardens was unveiled in December 1886. It was sculpted by George Blackall Simonds and decorated with a laurel frieze garland that ran around the top of the pedestal. The pedestal was originally faced with terracotta and brick but this was replaced with Portland stone in 1910.

The defeat at Maiwand came just 18 months after the disaster at Isandlwana in South Africa. According to David Gore’s Soldiers, Saints and Scallywags (209),

Maiwand is essentially the story of bravery and endurance in the most adverse conditions, and of unselfishness and dedication in a long and difficult retreat. It is about the extraordinary courage of the native infantry who, despite suffering huge casualties, stood therir ground in the open until finally overwhelmed by numbers; of the gallon sacrifice of those young British soldiers of the 66th who were surrounded but fought on around their colours to the last man. And there was the steadfastness of the cavalry who stood and suffered heavily through three hours of bombardment without being able to take any action. And finally there was the discipline of the horse artillery, who "maintained their military formation and morale throughout" and became the backbone of the retreat to whom, in the words of the Viceroy, “many survivors of 27th July owe their lives. [176-77; emphasis in orignal]

Although the British lost the battle of Maiwand, their prepared for General Roberts subsequent victory because the troops killed and injured so many of the Afghan forces — about 5500 dead and another 1500 seriously injured — so that when Roberts's attacked, he confronted a much weakened enemy.

Rudyard Kipling, the poet of British India, wrote a surprisingly critical piece about the battle called ‘That Day’ which focussed as much on the disorderly retreat towards Kandahar as it did on the heroics of the 66th. The following Kipling verse brilliantly describes the terror as men fled amongst horses, camels and camp followers in blind panic:

I ‘eard the knives be’ind me, but I dursn’t face my man,

Nor I don’t know where I went to, ’cause I didn’t ‘alt to see,

Till I ‘eard a beggar squealin’ out for quarter as ‘e ran,

An’ I thought I knew the voice an’ — it was me!

Unfortunately William McGonagall also focussed his limited poetic skills on that dreadful experience. The poem is entitled ‘The Last Berkshire Eleven’ and begins in his familiar style:

’Twas at the disastrous battle of Maiwand, in Afghanistan,

Where the Berkshires were massacred to the last man.

On the morning of July the 27th, in the year eighteen eighty,

Which I’m sorry to relate was a pitiful sight to see.

McGonagall continues

But the Berkshires stood firm, replying to the fire of the musketry,

While they were surrounded on all sides by masses of cavalry;

Still that gallant band resolved to fight for their Queen and country,

Their motto being death before dishonour, rather than flee.

Photographs by the author, which may be used without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the in a print one.]

Related Material in the Victorian Web

- British India (homepage including links to geography, individual cities, history, and architecture)

- Afghanistan (homepage including links to geography, battles, and major figures)

Related Material on the World Wide Web

- Biographies of the officers and men of the 66th (Reading site)

- David Gore, Soldiers, Saints and Scallywags: Stirring Tales from Family History. Published by the author, 2009. 167-85. Available from Google Books: (click here)

Created 1 March 2020