In his Introduction to this masterful survey, Philip Ward-Jackson notes that ‘Historic Westminster’, roughly the area within a one mile radius of Trafalgar Square, can claim the greatest density of public sculpture in the whole of London. 235 statues and monuments are listed on the useful maps at the beginning of the book, of which over 90 are on or near the ‘royal route’ between Buckingham Palace and Westminster Abbey.

Eros, Piccadilly Circus by Sir Alfred Gilbert, R. A. [Click on these images and those below to enlarge them.]

The entries are arranged alphabetically by street, which makes it relatively easy to locate familiar statues. It also has the unexpected result that the book begins (and ends) with modern works rather than old favourites like Nelson’s Column or Eros. Thus under ‘A’ we find Henry Moore’s Knife Edge Two Piece (1967, Abingdon Street) and Maggi Hambling’s Oscar Wilde Memorial (1998, Adelaide Street). Both were controversial in their day; one critic thought that the Moore work resembled two empty hot water bottles, while another described Hambling’s memorial as ‘a wilfully tacky, silly Tussaudian tragedy’, despite the Royal Fine Art Commission commending it as an ‘interesting and original idea’.

The last two entries (under ‘Whitehall’) were also controversial. The Memorial to the Women of World War II by John Mills (2005) was criticised for being ‘sinister’ and too close to the Cenotaph, while the Royal Fine Art Commission, after viewing the model for the Royal Tank Regiment Memorial by Vivien Mallock (2000), regretted that there had been no process of selection aimed at getting ‘a fine work of art’. Each monument had its doughty champion (respectively Baroness Betty Boothroyd and General Sir Antony Walker); both were unveiled by the Queen and are now accepted features of the London scene.

Criticism of any public monument in London is of course almost inevitable, even when the greatest care is taken over the selection of sculptor and sitter. A classic example is Richard Belt’s Lord byron, described by Jo Darke in her Monument Guide (1991) as ‘the worst statue in London’. Ward –Jackson does not discuss its artistic merits, but gives an entertaining account of the prolonged selection process, involving two international competitions (which attracted entries from Rodin and Alfred Gilbert) and resulted in the award of the commission to the young and relatively unknown Belt. It was later alleged that Belt had employed a ‘ghost’ to produce both the competition model and the final statue; and although he won the lengthy libel case, his reputation was ruined. Fittingly, his byron is virtually invisible on an ‘all but inaccessible’ island in Park Lane.

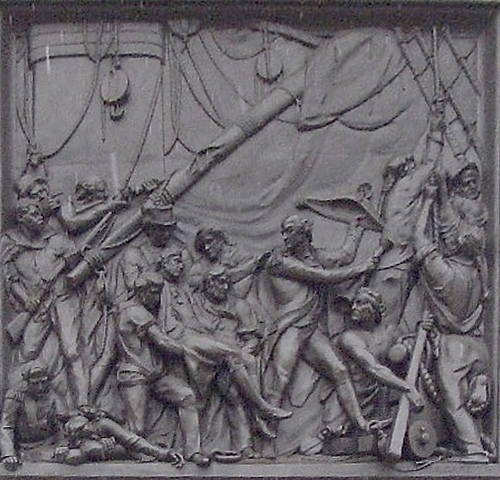

Left: Horatio Lord Nelson by E. H. Baily, RA. Middle: The Battle of the Nile by W. F. Woodington. Right: The Battle of Trafalgar also known as The Death of Nelson by John Edward Carew. For Sir Edwin Landseer's lions see immediately below.

Nelson’s Column (or more accurately The Monument to Lord Nelson) is given deservedly generous coverage, with full descriptions of the Column (Railton), the Statue (Baily), the Reliefs (Carew, Ternouth, Watson and Woodington) and the Lions (Landseer). We now take this great work for granted, but Ward-Jackson reminds us that while Dublin had its Nelson Column in 1808, it was not until 1838 that serious consideration was given to a national memorial in London. The statue was installed on the column by 1843, but it took a further eleven years to complete the four reliefs and the lions were finally unveiled in 1867, over sixty years after the Battle of Trafalgar.

Another familiar work which took some time to complete was the Victoria Memorial. In this case a single sculptor (Thomas Brock) was appointed, a design approved and a site chosen within a few months of the Queen’s death in 1901.

Left: The Victoria Memorial by Sir Thomas Brock RA. Middle: Peace. Right: The Army and Navy.

However, the sheer size of the monument meant that it was not ready for unveiling until 1911; and even then it was incomplete, as it lacked six massive bronze groups. The four figures with lions symbolising Peace, Progress Agriculture and Manufacture were installed in 1914, but the casting of the two fountain arches symbolising Art & Science and the Army & the Navy was delayed by the 1914-18 War. They were not placed in position until 1924, two years after Brock’s death and under the supervision of his son Fredrick.

Philip Ward-Jackson’s magnum opus is comprehensive, authoritative and a delight to read. The public monuments of Westminster are not only part of London’s history and culture but also an essential element of our national heritage. The author and Liverpool University Press are to be warmly congratulated on a handsome production, and we look forward to Volume 2 with keen expectation.

Brocks's European travels: an apology and correction in the form of a postscript

In commenting on Thomas Brock’s decision not spend a year visiting the great monuments of Europe to seek inspiration for his design of the Victoria Memorial, Ward-Jackson states (page 129) that Brock had ‘only once left the country, to visit Chicago World Exhibition in 1893’, citing my 2002 thesis on Brock. I must apologise to Philip, for I have led him astray.

I have since discovered that Brock in fact visited France prior to 1901. Frederick Brock notes in his memoir that his father spent part of the winter of 1899 in the south of France on doctor’s orders and also visited Paris, where he viewed Rodin’s Danaid in the Luxembourg Gardens (mss in V&A National Art Library NAL 86 ZZ 10, pages 152 and 175). This memoir, with a foreword by Dr Marjorie Trusted (Senior Curator of Sculpture at the V&A), is being published later this year under the title Sir Thomas Brock, forgotten sculptor of the Victoria Memorial. Further information from sankey@waitrose.com

Bibliography

Ward-Jackson, Philip. Public Sculpture of Historic Westminster. Volume 1.

Last modified 7 June 2012