[All images, with the exception of the one at top right and the heroic figure in the next line, come from the Metropolitan Museum's own site.]

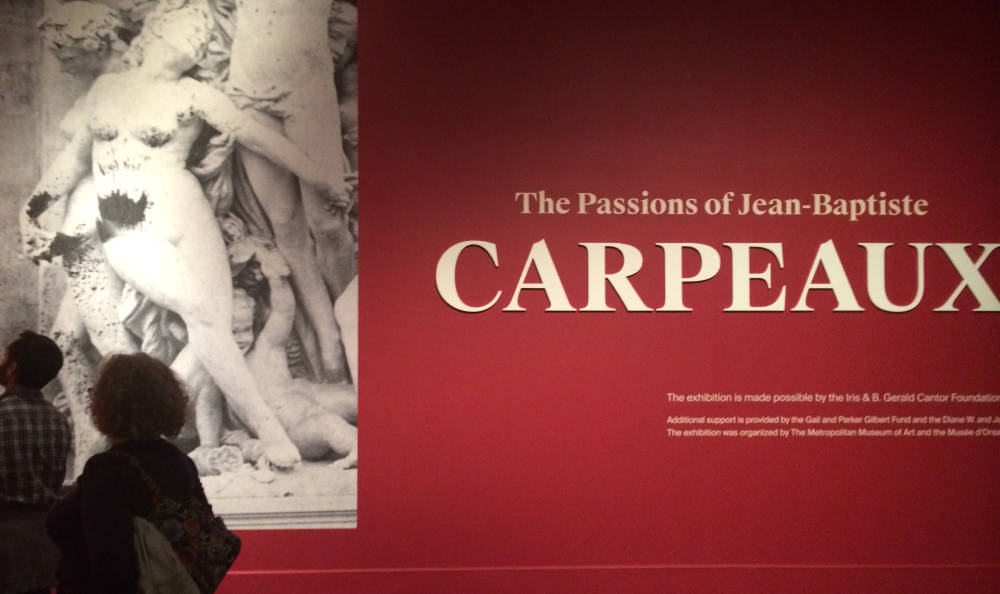

Four decades ago, when I was part of a group organizing an international exhibition of medieval ivories, the then-director of one of New England's finest mid-sized museums gave us the following advice: “You can mount a scholarly show or you can put together a popular one that many people will want to see. Make sure you don't create of those off-putting exhibitions that, however valuable to your own research, only a small number of specialists will find interesting.” The implication was that no matter how much specialized scholarly work went into creating the show, it also had, like the Met's current Carpeaux exhibition, to interest the average intelligent museum goer. Metropolitan Museum of Art's current show exemplifies an almost ideal museum exhibition: it takes a neglected, out-of-fashion master, intrigues us by revealing both perhaps unexpected virtuosity and an extraordinary range of skills and subjects. In other words, it follows the good old-fashioned neoclasssical dictum and surprises, entertains, and even intrigues in order to show us something new — that is, as Sir Philip Sydney would put it, “The Passions of Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux” entertains in order to educate us in the highest and best sense.

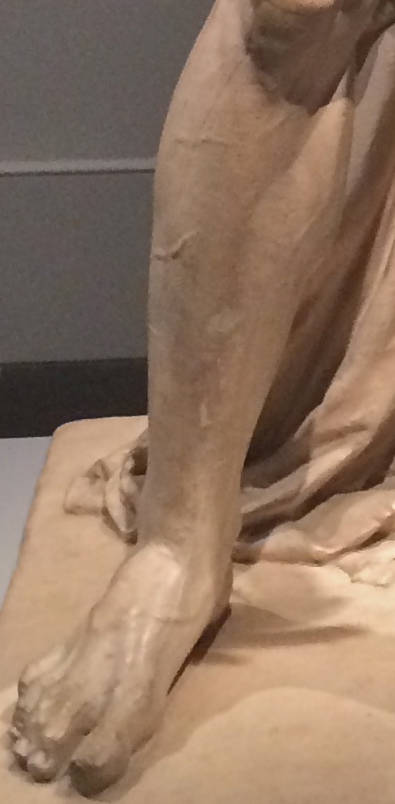

The central piece in the first room, the sculpture that earned him the coveted Prix de Rome, turns out to be a bravura work of contrasts beteween the muscled hero and the son he holds. However classical his subject, Carpeaux's depicting the veins on the warrior's legs rejects the smooth classicizing figures of Canova, Thorvaldson, Flaxman, Gibson, and other exemplars of a pan-European neoclassicism. As in much of his finest work, the sculptor devoted extraordinary energy and skill to depicting hands and toes.

The crown prince in many guises

Passing by two rather vapid kneeling figures, one a young man, the other a young woman, we come upon a second room and immediately encounter a different side of Carpeaux, here a sculptor exchanging power for elegance. Turning way from his Michelangeloesque nudes, he now portrays Napoleon III's adolescent son in elegantly casual sporting clothing as the boy pets his large dog. This room contains not only the marble version that appears in the photograph at right but also one rather dreadful silver-plated one, a bronze, and various reduced-size or partial versions. This room in the exhibition dominated by its multiple versions of the same figure, which obviously represents the scholarly side of the show, as it were, makes two very interesting points, the first of which, is that Carpeaux obviously followed standard nineteenth-century studio practice so that assistants did much of what we take to be Carpeaux's work and perhaps for that reason the expressions vary slightly from statue to statue. Secondly, given the tendency of both Victorian England and France of the Second Empire to present themselves as the obvious heirs to the power of Ancient Rome, the statue of the Crown Prince, like so many of Lawrence Alma-Tadema's paintings, presents an image, not of a stern, powerful imperium, but of a non-threatening upper-middle-class domesticity.

Dancers on Garnier's L'Opera

Encountering the sensual, ecstatic dancers Carpeaux created for the façade of the Paris Opera — probably his most famous work — we see another side of the sculptor — a delight in depicting movement and joy quite unexpected after the solemn adademic almost-classicism of his Prix de Rome work and the society portraiture of Napoleon III's son. These dancers scandalized some members of the public, one of whom defaced them by throwing ink upon them.

Uglino and his Sons

This larger-than-life statue of the scene in Dante's Inferno, which the Museum site quotes and explains in detail, reveals yet another side of Carpeaux. Again we see the emulation of Michaelangelo and again, as with the dancers of the Paris Opera, a work that powerfully weaves together multiple figures, but whereas they embodied grace, joy, and the heights of human pleasure, Uglino and his Sons seeks intensity of the romantic sublime and horrific grotesque.

Left to right: (a) Uglino's contorted feet embodying his physical and mental torment. (b) Uglino's grotesque facial expression . (c) Rear view of the statue showing its pyramidal composition. [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

Granted, as the museum chat labels instruct us, Carpeaux idolized both Michelangelo and Dante, but, still, why depict this scene of terrible despair — other than as a means of showing his emotional and technical range?

“I've never seen sculpture with so many happy people”: portraits of friends and patrons

The half smiles and looks of happiness on the faces of almost every one of Carpeaux's busts, which come as a real shock after Uglino and his Sons, make him a much more interesting portraitist than virtually all his British contemporaries. One thinks of the stolid, somber work of Thomas Woolner, though his bronze and marble busts of Garnier have much in common with Derwent Wood's Robert Brough. Certainly, Carpeaux did not always idealize his sitters, something demonstrated by the delightful portrait of a middle-aged woman friend who demanded a bust with warts, chin hair, and all, and that's what he gave her — and yet still made her look charming.

Carpeaux's bust of his wife. Amélie de Montfort Carpeaux

To a certain extent, the final rooms of the exhibition repeat the viewers' encounter with sharply opposed subjects and emotions. In the room in which we come upon Carpeaux's portrait bust of his lovely wife (and the mother of his four children), we learn that the sculptor, who seems to have been insanely jealous, had her followed even during her first pregnancy. More shocking perhaps is the Goyaesque drawing of his wife in the throes of childbirth. The surprises continue: an adjoining room containing some late religious work, informs us that that Carpeaux was a very religious man, something at which nothing in the exhibition had previously hinted, much less discussed. Like all fine exhibitions, it raises as many questions as it answers.

Last modified 22 April 2014