The images here come from our own website, and have been added by Jacqueline Banerjee. You may use them without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the source and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or to the Victorian Web in a print document. [Click on all the images to enlarge them, and for more information about them.]

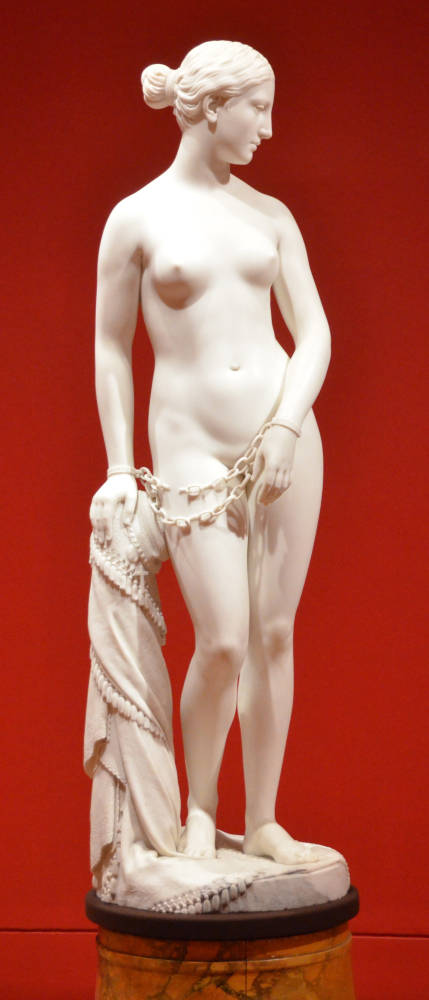

Hiram Powers's The Greek Slave.

Despite being dominated by its imposing early Victorian Town Hall, central Leeds is today an expansively modern city, and the Henry Moore Sculpture Gallery itself is ultra-modern. On entering its noiseless automatic glass doors, one again confronts a contradiction: immediately ahead is a life-sized statue of The Greek Slave (1844), by the American sculptor Hiram Powers — utterly distanced from reality by the smooth white marble of the sculptor's medium. This Neoclassical work serves as a silent, disconcerting greeting to a collection of exhibits at once enigmatic and revealing.

Throughout the exhibition, large wall panels offer helpful historical and social commentary, giving, for example, the full context of the slave trade. On this subject the panels explain what most visitors must know, but perhaps not in enough detail: that Charleston in South Carolina, and (much nearer at hand) Liverpool in north-west England, as well as various ports of embarkation in Ghana and elsewhere along Africa's north-west coast, were linked in a notorious "Triangular Trade" which dealt in African slaves, sugar cane and other plantation products, and manufactured European goods.

How did the artists of the time respond to this? Victorian sculptors have been criticised for continuing to pander to the dominant dilettante tastes of their numerous rich (masculine) patrons. Powers's "enigma" might have been motivated by abolitionist sentiments, but it cannot escape criticism in this respect. Separated from the visitor merely by a below-knee quadrant of square Perspex boxes, she passively offers a rare and 360-degree intimacy to the encroaching public. Her pose is that of the classical "Venus pudica" or "modest Venus," her upper thigh elegantly obscuring the genital region. Even so, the observer notes a marked absence of realistic detail: not only white, she is depilated. Doubtless with the scruples of any future purchaser in mind, the sculptor has also reduced the size and weight of her barbaric handcuffs and chain. Here they have more the appearance of delicate wrist bands, resembling women's jewellery rather than any darker historical and practical reality. Indirectly, at least, The Greek Slave reflects the wider social and moral anxiety beneath the surface of the age.

Close by, in a glass-topped wall display of contemporary books and periodicals, Linley Sambourne's full-page depiction of "Wooing the African Venus" from Punch magazine (22 September 1888), makes an interesting comparison with Hiram Powers's nude. A much more voluptuous woman, this "African Venus" is the very embodiment of a rich and fertile tranche of seized land in the east of the country. Sambourne shows her being ogled by the greedy colonialists who are about to take avantage of her. She seems rather a willing partipant in this transaction. But a snake rears its head in the middle foreground. There are dangers of all kinds here, to all concerned. The contemporary literature in this second room, opened at relevant pages, betrays similar tensions and complexities.

Linley Sambourne's full-page depiction of

Wooing the African Venus (1888).

While consideration of race adds considerably to the "anxiety" here, there were problems even without it. To the right of Powers's controversial work, the visitor finds another life-size female exhibit. Slightly earlier and far less restrained, this is The Hope Venus of 1817-20 by the Italian sculptor Antonio Canova. Canova's clients typically included Dukes, Popes and others from the highest strata of society, with his works inevitably reflecting the shared double standards of their time. Here the white female stance is shown as even more prominently "pudica," whilst the half-smiling face appears to be actually challenging the observer, with no coyly half-turned head or dropped gaze. This speaks of repressed sexual ambivalence, affording hidden wish-fulfilment to Canova's social circle, for whom he laboured to produce such concrete though disguised embodiments of their most hidden desires. The curators have brought out the tensions which would be analysed and laid bare by Sigmund Freud only towards the close of the Victorian period.

George Frampton's Lamia (1899).

The social anxiety of this time, about the progress of women into the public sphere, found expression in its sculpture too, witness the inclusion of figures like Sir George Frampton's Lamia — another striking work that features in the publicity of the exhibition. The eponymous subject of Keats's poem, her glittering woman's form, studded by Frampton with precious stones and metals, hides her true nature as a snake. The colour here is both disguise and warning. As Aymer Vallance wrote in 1889, when the work was still in the making, "The flesh parts are to be carried out in ivory, to meet the resources and limitations of which the artist has to exercise particular ingenuity, contriving to veil the joints of the material with an ornamental network of gold about the throat and forehead. The sleeves and drapery are to be of silver, embellished with mother-of-pearl and coloured enamels. The features are beautiful and full of dignity, and yet the expression is snake-like withal, as befits the character represented" (50).

Colour was relevant to the sculptor in a more general way. An exhibit on Antoine-Chrystome Quatremère de Quincy (1755-1849) tells how he overturned the prevalent Victorian myth of the lack of colour in classical sculpture. In 1814 he was the first to use the term "polychrome," and to inspire later experiments with adding colour to marble, as in John Gibson's The Tinted Venus. A truly realistic depiction of the female form was yet to come, however. As with the question of colour, controversy here could be heated, and long-lasting. To use a well-known example, critics still wonder whether such unrealistic depictions of the female form affected John Ruskin, whose marriage was never consummated: see James Spates's review of Robert Brownell's Marriage of Inconvenience). What is certain is the Victorian sculptors' hesitation to depart from earlier conventions in nude portraiture.

Left and centre: Two views of The Hope Venus, by Antonio Canova (1817-20). Right: John Gibson's polychromed marble Tinted Venus (1851-56).

Nevertheless, two sculptors in particular are represented by exhibits that did make greater efforts at Realism. John Bell's Octoroon of 1868 appears at first glance to be yet another delectable naked female. Closer examination, however, reveals the presence, especially on legs and thighs, of sores and bruising, whilst above one knee is evidence in scar tissue of a more serious wound - whether from accident in plantation work or maltreatment by overseers. Two other works of his, The American Slave of 1853, and The Manacled Slave of 1877, also deserve mention here — indeed, the latter is featured on the exhibition press release. French sculptor Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux (1827-75), interested in bringing both colour and detail into his work, is represented by a gilt-bronze plaster bust, "Why Born Enslaved!" This is a very strong depiction of a woman of decided character, whose anguished though undaunted face glares sideways at the onlooker, demanding to know why she had been so badly treated. Her hair is honestly depicted, in all the rigid grandeur of her afro-genetic origins, contradicting the restraining cords roped around the arms and shoulders.

Left John Bell's The American Slave (1853). Right: Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux's "Why Born Enslaved!" (1868-73)

In respect of this important racial element, the "elephant in the room," notable by its absence, is work which tried to engage more directly with the lives of black plantation slaves. Some exhibits from north-west Africa are added, including a face-masked figure representing the Dan peoples. There is also a dignified black female bust on loan from the royal collections. But there is nothing here of the kind of work shown, for example, at Rio de Janeiro's Museu Nacional de Belas Artes (National Museum of Fine Arts) in 2018. That exhibition, "From Slave Ships to Galleries," included imaginative reconstructions of the life of the plantation slaves during the Victorian period/Dom Pedro Regency period. Interestingly, Brazilian artists depicted female plantation workers in heavy European-style clothing, despite the tropical climate. These artists displayed nothing of the European penchant for idealized femininity and imputed sexuality — or the underlying anxiety that this penchant revealed.

Links to related material on this website

- Press Release for the exhibition

- Slavery and the Anti-Slavery Campaign in Britain

- A Gallery of Victorian Sculptural Nudes: Bound and Enslaved Women

- Andromeda — Women in Chains

- Polychromy in the work of Baron Carlo Marochetti (in four parts)

- Realism and the New Sculpture

- The Elgin Marbles, Polychromy, and Ancient Greek Art as an Aesthetic Ideal

Bibliography

From Slave Ships to Galleries: representations and agency of colored people in the National Museum of Fine Arts’s Collection. Google Arts and Culture. Web. 18 December 2022

Vallance, Aymer. “British Decorative Art in 1899 and the Arts and Crafts Exhibition. Part I” The International Studio (1899): 37-56.

Created 6 December 2022