Acknowledgements: Many thanks to Niamh Laboisse for her assistance and support, to Philip Ward-Jackson for assisting me in my inquiries, and to the Royal Collection, the Ville de Paris, the National Portrait Gallery and Marion Harris, New York for granting me reproduction rights. [Click on the images to enlarge them. Please see the bibliography at the end of Part IV for a list of all the works cited].

Queen Victoria as "Queen of Peace"

La Reine de la Paix by Baron Marochetti,” by Camille Silvy (1834-1910), albumen print (detail), 1861, NPG Ax55523 © National Portrait Gallery, London.

This polychrome statuette of Queen Victoria was exhibited in 1862 in the studio of its owner, the photographer Camille Silvy. The French art-historian Charles Blanc, who was in London at that time, wrote:

The Parian marble in which the figure is carved has entirely disappeared under a layer of bronzed colour, and it has lost the brilliance of its spangles which normally lend it vibrancy. The throne in antique red marble, has been covered with mosaics and enamels, and the work overall produces the effect of a jewel, of unusually large dimensions. [Blanc 566, qtd in Ward-Jackson's Marochetti catalogue, 2188]

The room enclosing this "remarkable work", lit” by stained-glass windows, looked like a chapel dedicated to a queen "both alive and allegorical" (Blanc 567). These words seem to have penetrated the artist's mind and expressed his wish to give life to his statue and make it an idol to worship. In a way, this statuette was a logical result of the peace trophy. In making the Queen an emblematic figure of Peace, Marochetti repeated an act of faith in polychromy. This time, he drew his inspiration from the Juno of Argos by Polycleitus, also reconstructed” by Quatremère de Quincy, and from the throne of Jupiter.

Left: Junon d'Argos, Pl. XX, in Quatremère de Quincy, Le Jupiter Olympien, 1815 © Gallica BNF. Right: Trône de Jupiter, Detail, Pl. XIII, in Quatremère de Quincy, Le Jupiter Olympien, 1815 © Gallica BNF.

The Queen — in full regalia — is represented in a similar pose, holding the royal sceptre in the right hand and an olive branch — the emblem of peace — in the other. The back of her throne is surmounted” by a bright crown on each side of which are placed two horns of plenty. The same pattern can be observed on the back of the throne of Jupiter.

John Gibson's Queen Victoria between Justice and Clemency (1850-7) had also been inspired” by Quatremère de Quincy, a friend of Canova, his master. He intended to paint his group but had to return to Rome in October 1856 before colouring it. However, on 10 February 1855, the Illustrated London News had reported: "the footstool is to be enriched with mosaic emblems; and the whole will be coloured and gilded" (see Darby 44).

Queen Victoria supported” by Justice and Clemency,” by John Gibson, Illustrated Times, 18 April 1857: 249 © The British Library Board.

Those details could not have gone unnoticed” by Marochetti, who shared with Gibson a deep interest in polychromy. It is worth noticing that, while the statuette could be seen in the photographer's studio in 1862, the Tinted Venus” by Gibson was displayed at the International Exhibition in a temple created” by Owen Jones. Both works were highlighted in a similar, although different way. Whereas Owen Jones housed Gibson's Venus in a Greek temple, Silvy Queen's room represented an Elizabethan frame for Marochetti's Queen of Peace, with sculptures painted in the Elizabethan style and tapestries of the same period. I am indebted to Philip Ward-Jackson for pointing out that Marochetti had certainly thought about the arts of that time when modelling his hunting group in massive silver for Charles Frederick Hancock (exhibited at the Great Exhibition in 1851), the subject of which was "The entry of Queen Elizabeth on horseback into Kenilworth Castle" (Great Exhibition, 692). In Silvy Queen's room, the reference to Queen Elizabeth I, whose long reign had marked the kingdom, could be seen also as a tribute to Anglo-Florentine polychromy, just as the pedestal of the Peace Trophy could be seen as one to the Middle Ages.

Group in Silver, Mr Hancock, Plate 13 (Great Exhibition, 692)

"This is both a monument in miniature and a colossal jewel," said Charles Blanc, praising it. The "polychromian" statuette of the Queen of Peace and Plenty was exhibited again after the sculptor's death "at M. Camille Silvy's studio during the three months of his last season as photographic portraitist" (Morning Post, 9 April 1868). Did he consider this work as the polychrome testament of the sculptor? In fact, this was, as far as is known, the last coloured work” by Carlo Marochetti. Camille Silvy, proud of being its owner, sent it one year later to Chartres for the 1869 Departmental Exhibition: "No. 231, a very remarkable statuette representing the queen of England" (Procès-Verbaux, 241). The meeting's minutes refer to the Parthenon Minerva and the Olympian Jupiter, and quote Charles Blanc's praise for the statuette. Charles Blanc was a well-known opponent of polychromy and considered Marochetti's statuette to be "the exception that proves the rule."

The statuette (untraced) most probably dates from the year when Camille Silvy photographed it in Marochetti's studio (around 20 August 1861, according to the other photographs on the same page of Silvy's daybook). Apparently, this photograph depicts the plaster model and not the final work: the throne does not seem to be in marble and there are no visible mosaics or enamels. Was it a commission? How did Camille Silvy happen to acquire it? Those questions remain unsolved. It is tempting to suggest that it could have been the last gift that Prince Albert intended to offer Queen Victoria for Christmas 1861. Victoria & Albert used to give each other works of art on their birthdays or at Christmas and, several times, Marochetti, who was close to Prince Albert, had been asked to create sculptures for that purpose. Moreover, Prince Albert was, for several years, "something of a convert to sculptural polychromy" (Darby 44). For the Chartres exhibition, Silvy composed an "Ode to the Queen of Peace and Plenty for the unveiling of the polychrome statuette” by Baron Marochetti at the Chartres Industrial and Artistic Exhibition, in May 1869," some verses of which seem to confirm that hypothesis:

Beautiful marble, the time has come for you to leave the hospitable island,

Where you secretly were my guardian angel,

Today I bring you to my native home!

I tear the veil and the fatal mourning cloth

By which you remained covered for eight years.

Marochetti could also have conceived this statuette as a project for a monumental work such as Peace by Antoine-Denis Chaudet (1806).

La Paix, 1806,” by Antoine-Denis Chaudet (1763-1810), 167 x 108 x 84cm. Musée du Louvre [background digitally removed — JB].

This seated female figure in silver, gilded silver, bronze, and gilded bronze was commissioned in 1803 to celebrate the Treaty of Amiens, signed” by France and Britain on 27 March 1802. Marochetti could have conceived such a monumental statue in memory of Queen Victoria's visit to Paris in 1855, symbol of the reconciliation between both countries. In that case, however, he would probably just have made the plaster model. Whatever the case may be, Prince Albert's death concluded the project. Indeed, as Philip Ward-Jackson mentioned in his catalogue, the Queen never visited Silvy's "royalist shrine." Silvy, who had photographed the work, could have asked Marochetti to sell it to him, and suggested displaying it in an intimate way — due to the Queen's mourning —, as opposed to the conditions in which Gibson's Venus was exhibited. This type of sanctuary was appropriate to the circumstances, and Silvy's room, completed in 1860 and furnished in the Gothic Revival style, was the ideal location for this shrine. It is worth pointing out that in 1862, in contrast to what happened six years later, the exhibition of the statuette in Silvy's studio was not announced in the press. In the meantime, the famous Nadar had seen a silver equestrian statuette of the Queen” by Marochetti, standing on the mantelpiece of Silvy Queen's room (Nadar 236). This was a reduction of the Glasgow equestrian statue (1854), cast in solid silver (see Ward-Jackson's catalogue, 2182).

Camille Silvy photographed Marochetti, his wife, and his son Maurizio, as well as many of the sculptor's friends. Indeed, Carlo Marochetti is considered as "one of Silvy's most important associates" for many reasons, one of them being that "his sculptures adorn many of the studio's cartes" (Haworth-Booth 71-2). Silvy was often asked to photograph the plaster models of Marochetti's sculptures. Both artists must have planned the display of the statuette together in 1862 (on the relationship between Silvy and Marochetti, see Ward-Jackson, "Carlo Marochetti et les photographes"). However, it is unlikely that Camille Silvy commissioned the statuette. Its mystery remains unsolved.

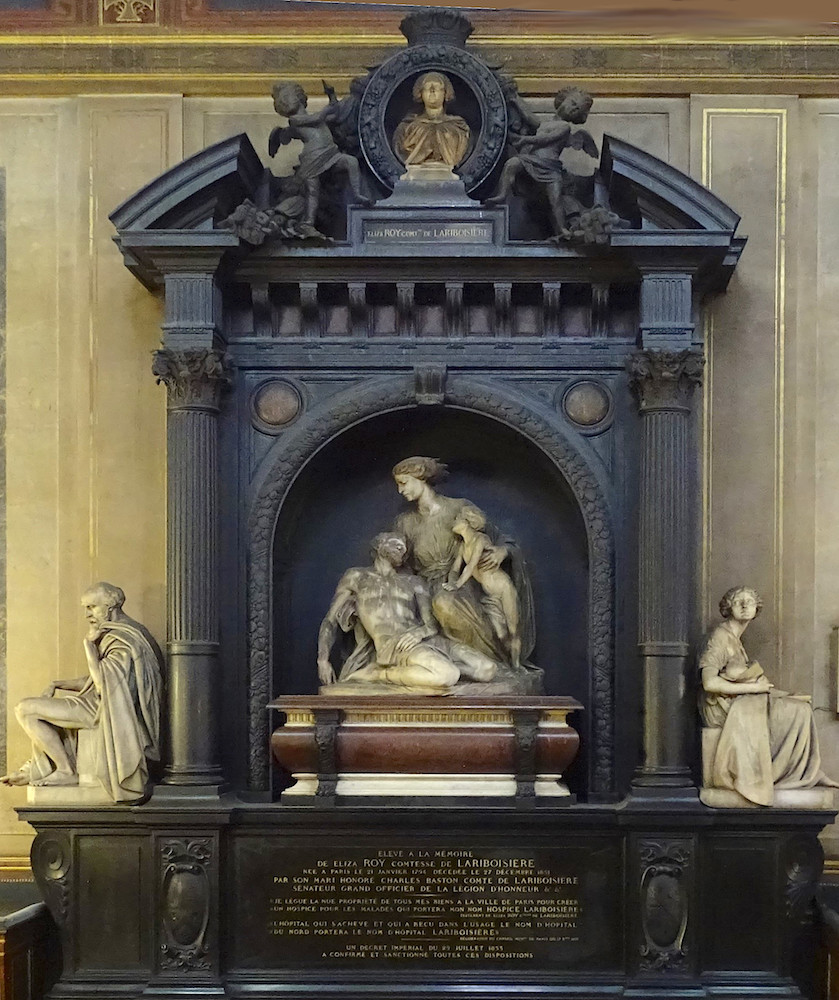

"A huge and imposing composition": Monument to Eliza Roy, Comtesse de Lariboisière

Tomb of Eliza Roy, Comtesse de Lariboisière, 1857, Paris, Hôpital Lariboisière.

Such were the first words describing the Monument to Eliza Roy, Comtesse de Lariboisière in the Gazette de France (7 June 1857). This important work, which deserves an entry of its own, will be considered here from the point of view of its polychromy. Praising "a most remarkable group, both in terms of its execution and the expression of the heads of the figures", the Gazette de France concluded:

The look of this monument is most remarkable. What makes it especially strange is that the artist has had the idea of colouring all his statues in the lower part. This is an innovation which critics will no doubt debate, but which produces a very great and dramatic effect in the half-light of the hospice chapel [qtd. in Ward-Jackson's catalogue, 2725]

The Courrier franco-italien was more accurate concerning the figures "all in marble and tinted," saying, "The colour is applied very lightly. Hair is coloured brown or fair, beards are black or grey. Draperies are also coloured" (11 June 1857). The central figure was described as "a gold-haired angel, with a yellowish robe."

Tomb of Eliza Roy, Comtesse de Lariboisière, 1857, Paris, Hôpital Lariboisière, details. Left: Central group. Right: Head of the central group's main figure.

The Italian sculptor Giovanni Dupré, recalling his visit to the hospital's chapel, disapproved of Marochetti's "loading on colour":

It is completely coloured — I should better say painted all over – with body colour, — the heads, hair, eyes, draperies, all coloured so that it is impossible to distinguish the material in which it is sculptured. You could distinguish absolutely nothing; and if it had not been for the custode, who affirmed that the work was in marble, you might have thought it was coloured plaster or terra cotta. [Dupré: 284-5, qtd.” by Ward-Jackson]

This was not a view shared” by Charles Yriarte: "The tendency to have marbles of several tones is an innovation, or rather a revival, that we would like to see more of" (Le Monde illustré, 21 February 1863, qtd,” by Ward-Jackson).

This ambitious polychrome monument for the chapel of the Lariboisière Hospital, erected to the memory of the benefactress, was created in London. Had Marochetti decided to use colour from the start (autumn 1853)? In any event, he certainly did in 1855-6, while he was working on his coloured marble busts. Maybe this is what Janet Ross alluded to in her memoirs. She recalled that, while William Millais was tinting the busts, she "was pressed into the service to sit for the colouring of a head in a large shell" (Ross 39). Was the large shell reproducing the shape of the monument's central recess? If so, William Millais might also have worked on the figures of the monument. Whatever the case, contrary to what Dupré has recorded, the colour was lightly applied, according to other visitors: Count Horace of Viel-Castel, who visited the chapel with Marochetti on 29 May 1857, found the monument "very beautiful" and the light colouring of the figures harmonious. "Greeks coloured their marbles, they were not wrong" (Viel-Castel 82). Auguste-Philibert Chaalons d'Argé, in his extensive review of the monument, declared: "this combination of colour and marble produces a considerable effect." He gave an accurate description of the colouring: "The artist's idea was not to paint these marble figures, but to lightly tint them. Thus the hair and the beard of the figures have their natural colour. The angel's robe is a golden yellow; the woman's dress and the old man's coat are a light green" (Ch. d'Argé 320). As for Paul Mantz, he wrote in Marochetti's obituary: "He went so far as to colour his figures with light, green, pink, and blue hues" (L'Illustration, 15 February 1868: 106).

Unfortunately, almost nothing remains of the colouring of what Charles Yriarte considered to be "one of Marochetti's finest works". A fire, devastating the sacristy on 28 February 1997 (Martineaud: 343), spread to the chapel and soot covered what was left of the tinting. Traces of drips can be seen on the statues, the remains of the firemen's intervention. However, some colour on the main figure's hair and dress can be discerned through the thick layer of dirt and dust.

Related Material

- Part I: The busts of Princess Gouramma of Coorg, Maharajah Duleep Singh, and Queen Victoria

- Part II: The Peace Trophy

- Part IV: Polychromy and materials (with Conclusion and Bibliography)

- "The Colour of Anxiety: Race, Sexuality and Disorder in Victorian Sculpture" [review of the exhibition at the Henry Moore Institute, London (2022-23)]

Created 4 June 2018