This article has been peer-reviewed under the direction of Professors Mary Elizabeth Leighton and Lisa Surridge (University of Victoria). It forms part of the Great Expectations Pregnancy Project, funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Abortion in nineteenth-century Britain was an issue occluded from the debates around birth control. Advocates of neo-Malthusian “prudential restraints” were extremely anxious to dissociate themselves from the idea that the two things were at all related. They argued that preventive measures associated with intercourse were greatly preferable to action undertaken to terminate pregnancy already in progress. This distinction was by no means clear in the popular mind, and during the scandal over Lord Amberley’s advocacy of contraception, he was depicted as a quack doctor selling bottles of “depopulation mixture” (Fryer, The Birth Controllers, plate VI).

The vast majority of abortion and attempted abortion occurred in a largely female subculture. Some illicit practitioners were male, and there is some evidence that men might be part of local networks of information on backstreet abortionists.

The Legal Position

Although the law took some recognisance of abortion before that date, the first statutory law in Britain was passed as part of Lord Ellenborough’s Act, 1803, concerned with interpersonal violence. The inclusion of “malicious using of Means to procure the Miscarriage of Women” (1803, 43 Geo. 3, c. 58, II) (following quickening) was in the context of recent cases of men giving their mistresses toxic substances in order to do away with inconvenient pregnancies. It was not part of any developing debate about population or state control over women’s bodies. The “quickening” proviso was dropped in 1837, thus extending the reach of the law.

Abortion was a common concealed practice among married women, almost certainly the majority of cases, desperate to avoid more children than family resources or their personal health could sustain. Changes in social attitudes, the economic opportunities for single mothers, and the laws concerning illegitimacy in the early decades of the nineteenth century led to a substantial rise in the numbers of single women procuring abortion. No longer able to sue the fathers for maintenance following the “bastardy clauses” in the 1834 New Poor Law, unwed mothers were likely, if the pregnancy continued, to fall into destitution or be confined in the workhouse.

In 1861 the Offenses Against the Person Act imposed stringent penalties for abortion lying far more heavily upon the woman herself:

58. Every Woman, being with Child, who, with Intent to procure her own Miscarriage, shall unlawfully administer to herself any Poison or other noxious Thing, or shall unlawfully use any Instrument or other Means whatsoever with the like Intent, and whosoever, with Intent to procure the Miscarriage of any Woman, whether she be or be not with Child, shall unlawfully administer to her or cause to be taken by her any Poison or other noxious Thing, or shall unlawfully use any Instrument or other Means whatsoever with the like Intent, shall be guilty of Felony, and being convicted thereof shall be liable, at the Discretion of the Court, to be kept in Penal Servitude for Life or for any Term not less than Three Years,— or to be imprisoned for any Term not exceeding Two Years, with or without Hard Labour, and with or without Solitary Confinement. 59. Whosoever shall unlawfully supply or procure any Poison or other noxious Thing, or any Instrument or Thing whatsoever, knowing that the same is intended to be unlawfully used or employed with Intent to procure the Miscarriage of any Woman, whether she be or be not with Child, shall be guilty of a Misdemeanor, and being convicted thereof shall be liable, at the Discretion of the Court, to be kept in Penal Servitude for the Term of Three Years, or to be imprisoned for any Term not exceeding Two Years, with or without Hard Labour. [1861, 24 & 25 Vict., c. 100, 58–59]

This law remains in force apart from the specific exceptions created under the 1967 Abortion Act. Already by the end of the nineteenth century it had become clear that these clauses had been drawn up prior to significant medical and surgical advances: by 1900, conducted under standard conditions of surgical antisepsis, abortion was an exceedingly safe operation.

While under this Act the woman herself was criminalised, it was very seldom that women appeared in court accused of procuring their own abortions. The act of abortion was undertaken in secrecy, often self-induced, and in probably most cases concluded without attracting medical attention. Even if it did, doctors acknowledged that natural miscarriages occurred in statistically significant numbers (Swaine Taylor 502), and it was by no means easy to determine whether one had been induced by the woman herself. If, however, a woman came under medical surveillance in mortal extremity following an operation performed by an abortionist or involving instruments, there might be endeavours to make her give up the name of any person who had aided her. This led to contention between the medical profession and policing and legal authorities. The latter felt that doctors ought to do more to obtain the names of accomplices, while medics considered that they retained a duty of confidentiality towards their patients, and furthermore should not be obliged to badger women in dire extremity.

“Bringing It On” and “Relieving Obstructions”

Abortion, in spite of these legal penalties, was rife. It does not seem that women in general apprehended that common practices for “bringing on” tardy menstruation—the terms in which the matter was usually framed—were anything that fell within the purlieu of the law, rather than the realm of domestic personal healthcare. Besides such expedients as violent physical activity, numerous traditional remedies continued in use: apiol, pennyroyal, savin, ergot of rye, aloes and iron, quinine, arsenic, slippery elm. All of these were dangerously toxic, with the dosage necessary to induce miscarriage very close to the lethal dose. Following an epidemic of miscarriages in Sheffield after lead contamination of the local water-supply during the 1890s, local women got in the practice of taking diachylon pills for deliberate abortion, an expedient which spread slowly by word of mouth (McLaren 242).

Clear glass shop round for Pennyroyal water. Courtesy of the Science Museum Group, © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum, object number A632692, kindly released under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) Licence.

However, there was also a growing and substantial commercial trade in “female pills,” claiming to be a “boon to womankind” (e.g. advertisement for Dodd’s Female Pills, Lloyd's Weekly Newspaper, Feb 8, 1891, 5) and “invaluable to married women,” (e.g. advertisement for Ottey’s Unlabelled Strong Female Pills, Croydon Observer, Jul 5, 1895, 1) widely advertised in the press, using coded language of “irregularities” (e.g. advertisement for the The Only Genuine Widow Welch’s Pills. Liverpool Mercury, May 19, 1837, 5) and “remov[ing] all obstructions” (e.g. advertisement for Dr Locock’s Female Wafers, Dundee, Perth, and Cupar Advertiser, Jan 1, 1850, 4). (A certain deniability was provided by the standard inclusion of “all female complaints” and “distressing symptoms” as also benefitted.) While traditional abortifacient substances might be alluded to—“where Steel and Pennyroyal fails” (e.g. advertisement for Ottey’s Strong Female Pills, Lichfield Mercury, Jan 13, 1899, 2)—or even used in the name (e.g. advertisement for Howell’s Aromatic Steel and Pennyroyal Pills, South Wales Daily News, Apr 24, 1875, 7), the pills themselves were largely spurious.

The Chrimes brothers not only dealt in fraudulent mail-order “female remedies” at exorbitant prices for desperate women, but they also then sent letters blackmailing the women who purchased them. The uncovering of this racket—the husband of one of the women who was sent an extorting letter read it and took it to the police in 1898—revealed the previously unsuspected extent to which women were seeking to terminate suspected pregnancies by this means. The evidence produced during the prosecution of the case indicated that thousands of letters had been received at the Chrimes’ offices over a period of two months (McLaren 232–38).

Poster advertisement for “Baldwin’s Herbal Female Pills.” Courtesy of the Wellcome Collection.

The Chrimes case was unique in providing court evidence of the extent of their trade, but the demand can be further substantiated from the huge number of advertisements in local and national papers for such pills. As the ingredients themselves were exceedingly cheap, the main expense involved must have been marketing. While most purveyors of these alleged remedies stuck to the small ad columns, handbills, and the catalogues and windows of “rubber-goods” shops to promote their wares, “Madame Frain’s Herbal or Medical Institute” sent out large numbers of women dressed as nurses to the suburban areas of major cities to distribute handbills (McLaren 239–40). The grossly inflated prices of the remedies themselves must have completely recompensed such initiatives. They would have presumably gained a certain degree of credibility from instances in which they “worked,” either because the woman was not pregnant and only had a delayed period, or because the woman had a miscarriage in the normal course of events.

There are hints that shops purveying remedies might sell stronger and stronger pills, and when all failed to work, would offer to “take away” the trouble (i.e., provide backstreet abortion).

Photograph of a grocer’s shop (actually a “hygienic stores’” or “rubber goods shop”) in England, showing the doorway and shop window. Courtesy of the Wellcome Collection.

Those who came to the attention of the law in connection with procuring illicit abortions, usually when the woman in question died, were both male and female. Sometimes a male partner had endeavoured to terminate a lover’s unwanted pregnancy. On a more professional level, recorded occupations included chemist, herbalist, medical botanist, and “unqualified practitioner”: in some cases the accused was described as a surgeon or medical man, but it is not always certain that this implied duly qualified in the eyes of the law. In a few instances the woman accused was stated to be a midwife (not a formal, licensed, qualification until 1902) but more often no particular occupation was given, suggesting backstreet amateur “helping out” among neighbour women.

Doctorly Discretion

The subject of abortion was naturally of concern to the medical profession, which, in particular since the setting up of a central regulatory body, the General Medical Council, in 1858, was increasingly concerned about defining and defending its respectability and professional standards. The possibility that a well-meaning doctor might end up in court and struck off the Medical Register was rather more influential in driving doctors’ attitudes than professional male complicity with notions of women’s essential reproductive function and the selfishness of women attempting to avoid maternity, or a refusal to conceal female sexual misconduct.

Title page and page 502 of Alfred Swaine Taylor’s A Manual of Medical Jurisprudence (London: J. & A. Churchill, 1879), showing the beginning of Taylor’s chapter on “Criminal Abortion.” Courtesy of the Wellcome Collection.

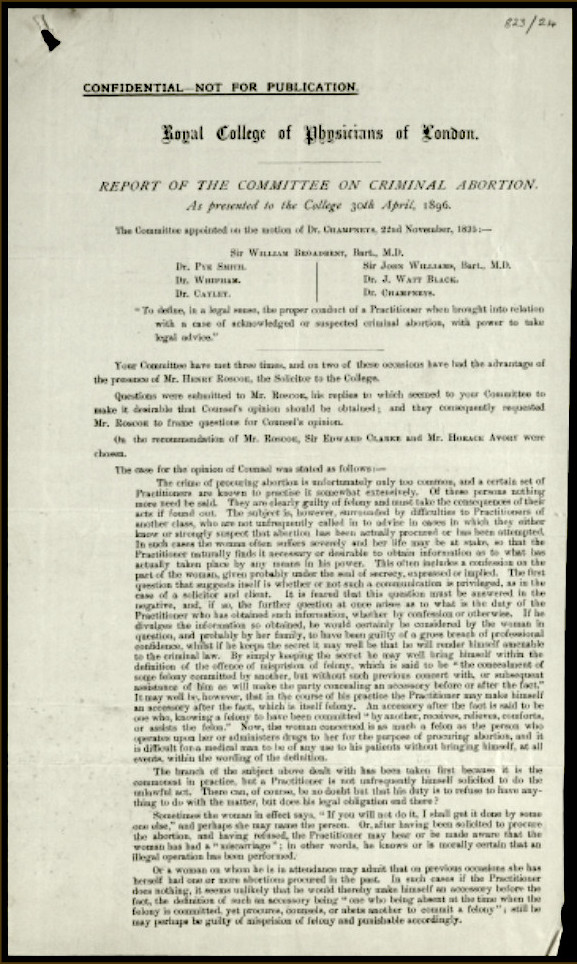

Even so, there was considerable leeway for doctors to make decisions according to their personal clinical and moral judgements. It was, indeed, argued that there were instances when the conscientious doctor had a moral obligation to perform an operation on clinical grounds to “induce premature labour,” to “give a chance of saving the life of a woman, when, by neglecting to perform it, it is almost certain that both she and the child will perish” (Swaine Taylor 522). Consultation with others of his profession was advised (the back-covering “second opinion” which remains inscribed in the 1967 Abortion Act). Counsel to the Royal College of Physicians gave the opinion in 1896 that “the law does not forbid the procurement of abortion … [where it] is necessary to save the mother’s life” (Report of Committee On Criminal Abortion). There are hints that it was also fairly common knowledge that certain specialists were prepared to undertake terminations for suitable remuneration.

Report of Committee on Criminal Abortion, as Presented to the College. 1896. Courtesy of Wiley Digital Archives, © John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Source: The Royal College of Physicians-Part II, Sir William Henry Willcox papers, reference number MS 823/24.

Doctors were additionally nervous about the hazardous position they might be in if they found themselves called in to treat women whom they suspected of having induced themselves or undergone an abortion. They might be supposed to have been guilty themselves of performing the operation. It was recommended to ensure that there were witnesses to the woman’s state at the time they arrived. On top of this anxiety, doctors found themselves criticised by the legal authorities for not doing more to extract information on abortionists from dying women if they suspected criminal abortion had taken place. It was therefore a subject that they felt most comfortable discussing with extreme discretion within the confines of their own profession.

It is very probable that abortion played a significant part in family limitation and the population decline of the later decades of the nineteenth century. Successful efforts to terminate pregnancy very likely greatly outnumbered those that ended in death (evidence from the pre-antibiotic, pre-blood transfusion early decades of the twentieth century suggests that many backstreet abortionists had long records of successful operations before the one that went disastrously wrong and found them in court; and some women reported safely self-aborting several pregnancies) (see e.g., Brookes 26–40; Brooke 108–11; Fisher 213–32). However, there must have been a great deal of ill-health caused by women taking toxic substances, which may not even have had the effect desired. There was also the pernicious commercial exploitation of women’s anxieties over unwanted pregnancy by the industry in “female pills.”

Links to related material

Bibilography

Brooke, Stephen. Sexual Politics: Sexuality, Family Planning and the British Left from the 1880s to the Present Day. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Brookes, Barbara. Abortion in England, 1900–1967. London: Croom Helm, 1988.

Fisher, Kate. “‘Didn’t Stop to Think, I Just Didn’t Want Another One’: The Culture of Abortion in Interwar South Wales.” In Sexual Cultures in Europe: Themes in Sexuality, edited by Franz Eder, Gerk Hekma, and Lesley A. Hall, 213–32. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1999.

Fryer, Peter. The Birth Controllers. London: Secker and Warburg, 1965.

Lord Ellenborough’s Act: An Act for the further prevention of malicious shooting and attempting to discharge loaded fire-arms, stabbing, cutting, wounding, poisoning and the malicious using of means to procure the miscarriage of women. 1803, 43 Geo. 3, c. 58. The Statutes Project. Web. 7 February 2022.

McLaren, Angus. Birth Control in Nineteenth-Century England. London: Croom Helm, 1978.

Offences Against the Person Act 1861: 1861 CHAPTER 100: An Act to consolidate and amend the Statute Law of England and Ireland relating to Offences against the Person. 1861, 24 & 25 Vict., c. 100, 58–59. Legislation.gov.uk. Web. 7 February 2022.

“Report of Committee on Criminal Abortion, as Presented to the College.” Sir William Henry Willcox papers, 29 Jan. 1896, Royal College of Physicians – Part II, MS 823/24. Wiley Digital Archives. Web. 7 February 2022.

Swaine Taylor, Alfred. A Manual of Medical Jurisprudence. London: J. & A. Churchill, 1879. Wellcome Collection. Web. 7 February 2022.

Further Reading

This is an area lacking the extensive historiography of birth control for the same period. There is an excellent pioneering chapter in Angus McLaren’s Birth Control in Nineteenth-Century England (London: Croom Helm, 1978). Eagerly anticipated is Judith A. Allen’s “Black Market in Misery”: Criminal Abortion and British Sexual Cultures, 1780–1980 (in progress). For nineteenth century medical understanding and attitudes, see e.g., Alfred Swaine Taylor, A Manual of Medical Jurisprudence (London: J. & A. Churchill, 1879, and numerous other editions), among the plethora of works being produced on forensic medicine, as well as textbooks on obstetric and gynaecological medicine. The digitisation of large numbers of newspapers makes highly visible the trade in “female pills,” as well as reports of trials for “procuring abortion” and “illegal operations.”

Created 15 July 2022