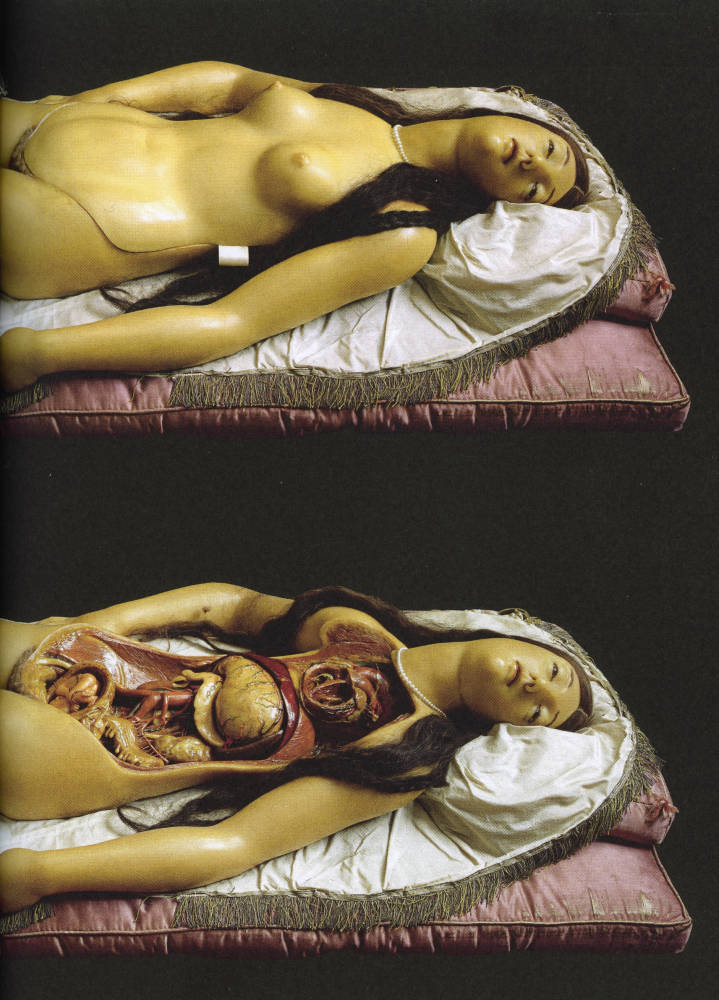

etween 1780 and 1782, the sculptor

Clemente Susini (1754-1816) found himself engaged in a strange project: to create

a life-sized wax model of nude, supine woman that could be dissassembled for

the purposes of anatomical instruction. The torso of the "Anatomical Venus," as the

object came to be known, was fitted with a lid that, when lifted,

permitted the anatomically-correct interior to be unpacked like a suitcase. As the

eighteenth century drew to a close, Susini and his artisans churned out thousands of

these objects for use by students and teachers at European medical schools. The wax

models tended to be not only female but also ethereally pretty; a deluxe

edition might feature a pregnant woman complete with

a fetus (or two) and placenta. They often had real hair. These models, also known as "Slashed Beauties" or

"Dissected Graces," can still be seen in various European museums such as the history of

science museum in Florence, where Susini developed the Venus in an attempt "to create an

encyclopedia of the human body in wax." (18) With this volume, Ebenstein

hopes to shed light on "why the Anatomical Venus has

come to seem so strange to modern sensibilities, a classic example of the uncanny." (19)

etween 1780 and 1782, the sculptor

Clemente Susini (1754-1816) found himself engaged in a strange project: to create

a life-sized wax model of nude, supine woman that could be dissassembled for

the purposes of anatomical instruction. The torso of the "Anatomical Venus," as the

object came to be known, was fitted with a lid that, when lifted,

permitted the anatomically-correct interior to be unpacked like a suitcase. As the

eighteenth century drew to a close, Susini and his artisans churned out thousands of

these objects for use by students and teachers at European medical schools. The wax

models tended to be not only female but also ethereally pretty; a deluxe

edition might feature a pregnant woman complete with

a fetus (or two) and placenta. They often had real hair. These models, also known as "Slashed Beauties" or

"Dissected Graces," can still be seen in various European museums such as the history of

science museum in Florence, where Susini developed the Venus in an attempt "to create an

encyclopedia of the human body in wax." (18) With this volume, Ebenstein

hopes to shed light on "why the Anatomical Venus has

come to seem so strange to modern sensibilities, a classic example of the uncanny." (19)

The book consists of five essays on different topics related to the Anatomical Venus as well as a substantial introduction. The first essay sets the Anatomical Venus in broad historical context, delving into the Renaissance origins of anatomical waxworks. They have a mixed genealogy as institutionally-sanctioned tools for medical instruction, on one hand, and objects of popular interest, curiosity, and awe, on the other. The second essay, "From Sacred to Scientific Use of Wax" investigates the material history of wax in the production of many kinds of human-like figures, from religious relics to the Anatomical Venus. A third essay, "Venus at the Fairground," considers the Anatomical Venus in relation to popular culture, exploring how the use of these objects for public instruction could not always be distinguished from paternalistic efforts to discourage behaviors, usually sexual, believed to be morally suspect. A fourth essay, on "Ecstasy, Fetishism, and Doll Worship," considers the Anatomical Venus in relation to other three-dimensional representations of the human body, from Barbie to blow-up sex doll. The final essay, "Venus, the Uncanny and the Ghost in the Machine," is the most ambitious of the set. It theorizes the unease typically evoked by contemporary viewers of the Anatomical Venus in terms of the "uncanny valley," the odd psychological zone identified by robotics professor Masahiro Mori in 1970, in which viewers of anatomical waxworks and other human effigies tend to find themselves. In 1970, Ebenstein writes, Mori noticed that "up to a point, the more human an object or being appears, the more affinity we feel towards it. However, objects or beings such as mannequins or zombies, which are very similar to us while remaining distinctly other, provoke unease or revulsion." (203) Eberstein suggests that responses to the Anatomical Venus fall squarely within this zone, and perhaps they do. Certainly the lushly photographed anatomical waxworks used to illustrate the book do little to undermine the notion. The volume also includes a bibliography that, while not extensive, is studded with intriguing gems, including pointers to intriguing monographs devoted to Susini and to the general history of anatomical waxworks.

Left: The title-page and frontispiece. Middle and Right: Photographs of the wax models in various stages of disassembly. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Ebenstein is a fine guide to the uncanny valley, especially where it intersects with Victorian kitsch. With Dr. Pat Morris, Ebenstein is author of Walter Potter's Curious World of Taxidermy (2013), a study of the Victorian taxidermist who dressed dead animals -- including, shockingly, kittens -- in contemporary garb and posed them as if they were engaged in ordinary activities, pouring tea and smoking cigars. She is also co-founder and creative director of the Morbid Anatomy Museum in Brooklyn, which not only houses a research library and a publicly viewable collection of anatomical and natural historical specimens, but also offers classes in, among other things, mouse taxidermy and the construction of insect shadowboxes. Dedicated to "to the celebration and exhibition of artifacts, histories and ideas which fall between the cracks of high and low culture, death and beauty, and disciplinary divides," according to its website, the museum developed from Ebenstein's blog dedicated to the same subjects and, like the blog, memorializes varieties of embodied twee. Lending ballast to Ebenstein's palpable enthusiasm, her experience with museum work keeps the book from being yet another odd object that, like the Venuses themselves, produces more awe than edification.

Nevertheless the real star of these pages is the Venus herself, in all her variations, imitations and descendants. The waxworks are spectacularly photographed, in rich color, from intimate angles. One is rarely so privileged to peer so closely into the interior reaches of the body. The photographs capture the astonishing beauty of these objects along with their equally astonishing capacity to horrify. Coming to terms with the uneasy fascination evoked by Anatomical Venus, Ebenstein suggests the limits of empirical investigation, of we can know simply by looking. Disassembling the Anatomical Venus paradoxically leaves the knowledge-seeker dissatisfied. Shouldn't we be made of something more, or other, than this dark and slimy tangle of guts? The Anatomical Venus sounds the depth of our emptiness and lets it reverberate.

Bibliography

Ebenstein, Joanna. The Anatomical Venus: Wax, God, Death & the Ecstatic. New York, NY: D. A. P./Distributed Art Publishers, 2016.

created 7 July 2016; last modified 8 September 2023