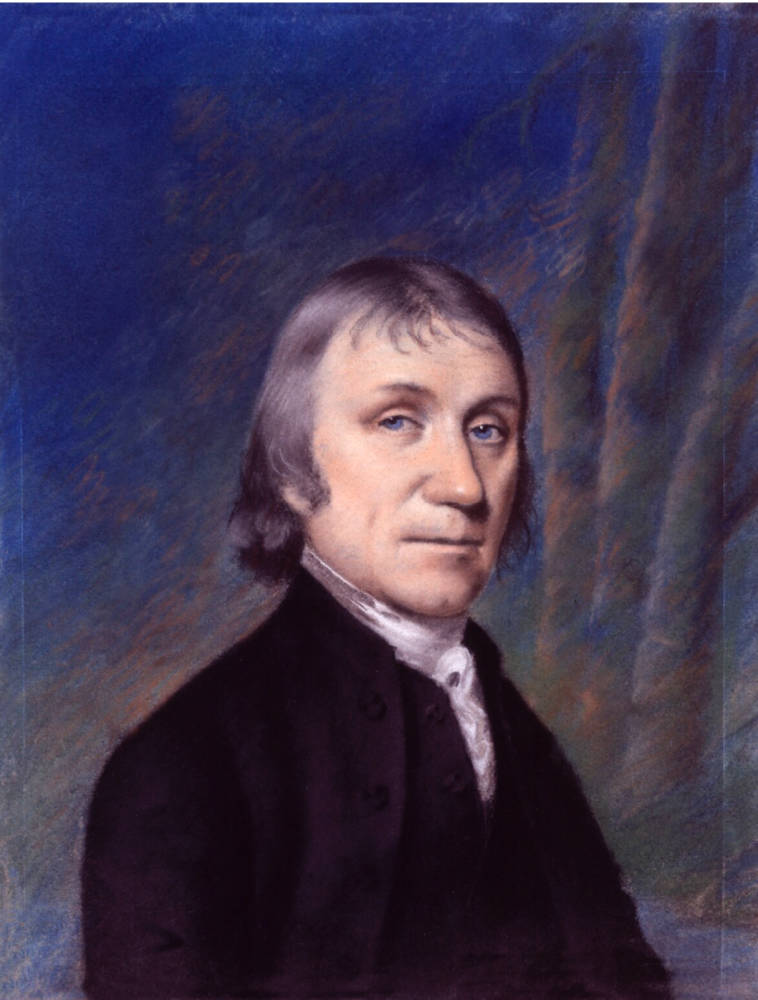

Joseph Priestley by Ellen Sharples. 1797. Courtesy Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, London. Click on image to enlarge it.

Hartley’s Observations had tremendous impact on the progressive mind of Joseph Priestley (1733-1804). The founding father of Unitarianism considered Hartley’s account a “new and most extensive science” and declared that he feels “more indebted to this one treatise, than to all the books I ever read, beside; the scriptures excepted” (Priestley, xix; quoted in Allen). In his double qualification as philosopher and chemist (and the discoverer of oxygen!), Priestley was the perfect embodiment of the Unitarian union of science and religion.

The idea that the human mind is a tabula rasa which develops in line with its association of perceived sensations offered a wholly new outlook on man: The rejection of innate ideas or proclivities emphasized the crucial role of the environment in the formation of character. The inequalities and differences between human beings are hence social and alterable. This Unitarian conviction was also fueled by their idea of Jesus as human (rather than God’s son), whose mortality had little, if any, bearing on his moral perfection. The Unitarians believed in the perfectibility of all human beings, and, according to Ruth E. Watts, “their strong naturalist psychology saw man as a bundle of potentialities to be developed.”

They tried to realize this on the individual as well as the social level: For one, Unitarians were strongly dedicated to self-education and self-improvement; a pursuit that was further encouraged by their particular cosmology: According to Gleadle, “Unitarians held that the universe was governed by laws, laid down by God. The object of a Unitarian life was to try and discover these laws so that one might better follow the Maker’s divine plan” (11). Scientific progress and the development of one’s potential thus became questions of religious duty. These endeavours were not limited to academic pursuits. Instead, the Unitarian bent for science and innovation had huge bearing on the business environment of the 19th century: famous companies like Wedgewood and Flowers were founded by Unitarians, as were approximately 66 per cent of all manufacturers in North Cheshire (Harrop, quoted in Gleadle, 12).

Still, given the Unitarian rejection of predestination and their belief in the equal endowment of all people, their trust in the importance (and possibility!) of personal progress had nothing elitist about it. Rather, it turned into a decisive social factor. The Unitarian emphasis on individualism changed not only the political but also the educational landscape of Great Britain. Unitarians played a pivotal role in the abolitionist movement (Stange), the Catholic Emancipation (Gleadle) and the Reform movement (Seed).

Besides, the Unitarian belief in the malleability of all people based on the theories of Locke and Hartley shaped their ideas on education. However, their progressive educational views worked in a less direct way than their political campaigns. Like all other dissenting groups, Unitarians were not granted access to higher education. They hence established their own educational institutions, such as Bedford College, King’s College and Manchester College (Watts, Webb), to name a few, and devised their curricula with a special focus on science, natural history, and the modern languages.

Related Material

- Introduction

- Philosophical foundations of Unitarianism – John Locke, Moral Sense, and David Hartley

- “Loose the female mind” – Unitarianism and feminism

- The Unitarian Radicals

- The Monthly Repository

- Unitarianism and Utilitarianism

- The Philosophic Radicals

Bibliography

Allen, Richard. “David Hartley.” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Ed. Edward N. Zalta. Summer 2020 Edition. Web. August 16, 2020.

Gleadle, Kathryn. The Early Feminists. Radical Unitarians and the Emergence of the Women’s Rights Movement, 1831-51. London: MacMillan, 1998.

Harrop, Sylvia. “The Place of Education in the Genesis of the Industrial Revolution with Particular Reference to Stalybridge, Dukinfield and Hyde.” MA-thesis. University of Manchester, 1976.

Priestley, Joseph. An Examination of Dr. Reid’s “Inquiry into the Human Mind on the Principles of Common Sense,” Dr. Beattie’s “Essay on the Nature and Immutability of Truth,” and Dr. Oswald’s “Appeal to Common Sense in Behalf of Religion”. London: J. Johnson, 1774.

Seed, John. “Theologies of Power: Unitarianism and the Social Relations of Religious Discourse, 1800-1850.” In Class, Power, and Social Structure in British Nineteenth Century Towns. Ed. R.J. Morris. Leicester: Leicester University Press, 1986. 108-56.

Watts, Ruth E. “The Unitarian Contribution to the Development of Female Education, 1790-1850,” History of Education 9(4) 1980: 273-86.

Last modified 24 September 2020