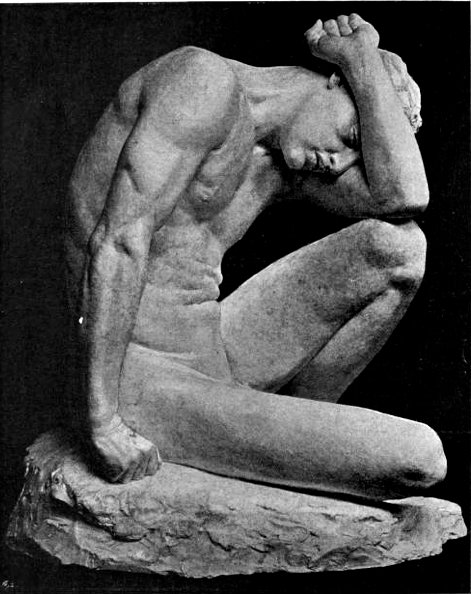

Cain. “My punishment is more than I can bear” by E. Roscoe Mullins, 1896.

In 1821, Byron wrote a drama entitled Cain which shows the world after the fall of the first humans, Adam and Eve. Cain, like Manfred, is an example of a literary genre known as closet drama, or off-stage drama. On the philosophical and theological level, Manfred, Cain and Heaven and Earth are thematically related works on human predestination. Cain suffers because he knows that he will someday die, and Manfred suffers because he lives. Both protagonists feel miserable and dejected in an alien and incomprehensible world. Cain is the murderer of his brother Abel, and Manfred feels responsible for the death of his beloved sister Astarte.

Of all Byron's dramatic plays, Cain is the most controversial and continues to attract the attention of critics to this day. From childhood, Byron was preoccupied with the issue of human predestination. In Cain, the poet asks poignantly the rhetorical question why evil exists if Jehovah is good. In the biography written by John Galt, the author quotes a conversation between Byron and a certain Dr. James Kennedy about predestination shortly before the poet's untimely death:

I already believe in predestination, which I know you believe, and in the depravity of the human heart in general, and of my own in particular. I am influenced in a way which is incomprehensible, and am led to do things which I never intended; and if there is, as we all admit, a Supreme Ruler of the universe; and if, as you say, he has the actions of the devils, as well as of his own angels, completely at his command, then those influences, or those arrangements of circumstances, which lead us to do things against our will, or with ill-will, must be also under his directions. [Galt 277]

Raised by a Scottish nurse, Agnes Gray, who instilled in him the Calvinist dogma of predestination, in adulthood Byron did not fully shake off its negative influence and believed that he would be inevitably damned. The nurse told him the tragic story of Cain and Abel, making him understand that there was nothing a man could do to change his predestined fate. Cain was an attempt to show in a dramatic form the poet's contention about the issue of the existence of evil in the world created by God. The plot of the drama begins after the expulsion from Paradise, when Cain refuses his father to participate in a prayer of thanksgiving dedicated to the Creator. While everyone praises Him, Cain remains silent. He has no intention of thanking the Creator who denied him immortality.

Adam: But thou my eldest born? art silent still?

Cain: 'Tis better I should be so.

Adam: Wherefore so?

Cain: I have nought to ask.

Adam: Nor aught to thank for?

Cain: No.

Adam: Dost thou not live?

Cain: Must I not die? [I.i.]

After being expelled from Paradise, Adam and Eve live with their sons, Cain and Abel, daughters Adah (Cain's wife-sister) and Zillah, and grandson Enoch, the son of Cain and Adah. Cain is angry with God for planting the Tree of Knowledge in the Garden of Eden. He resents his mother Eve for succumbing to the temptation of the Serpent and gathering the forbidden fruit. He is also furious with his father Adam for not harvesting the fruit from the Tree of Life: "And wherefore plucked ye not the tree of life? / Ye might have then defied him" (I.i). He is even annoyed at his younger brother Abel for not being as discontented as he is. Later, Cain meets Lucifer, a fallen angel, and tells him that although he has eaten the Fruit of Knowledge, he still does not know what Death is, which he imagines as a fearful anthropomorphic being. Cain sees his mortality as an unjust punishment for the sin of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden and the prospect of death makes him reluctant to enjoy short-term pleasures.

In Act II, Lucifer takes Cain on a journey to the "Abyss of Space" and shows him a catastrophic vision of the Earth's natural history, a small star among millions of other stars, along with the spirits of extinct life forms, such as mammoths and behemoths. Finally, Lucifer carries Cain to the gates of Hades. Lucifer explains to him that the phantoms flying around are the spirits of beings that God had created and destroyed before He begat Adam and Eve. Cain is presented with a terrifying vision of the sins and suffering that will haunt humanity. All this depresses him so much that he simply wants to die. He asks to be left behind in Hades, but Lucifer tells him that it is still too early.

Cain: No: I'll stay here.

Lucifer: How long?

Cain: For ever! Since I must one day return here from the earth, I rather would remain; I am sick of all That dust has shown me - let me dwell in shadows.

Lucifer: It cannot be: thou now beholdest as A vision that which is reality. To make thyself fit for this dwelling, thou Must pass through what the things thou seest have passed - The gates of Death.

Cain: By what gate have we entered. Even now?

Lucifer: By mine! But, plighted to return, My spirit buoys thee up to breathe in regions Where all is breathless save thyself. Gaze on; But do not think to dwell here till thine hour Is come! [II.ii.]

Cain does not understand why Almighty God tolerates evil in the world. Byron was almost obsessively interested in the existence of evil and the suffering it causes in unfortunate people. Embittered by the vision of omnipresent evil and inevitable death, Cain returns to Earth in Act III. He and his sister-wife Adah watch their son Enoch sleep. Cain claims that Enoch is smiling because he is still too young and innocent to know that Paradise is lost for ever. For a moment, he considers killing his own son to protect him from the suffering and misfortunes of earthly life, but, scolded by Ada, he does not commit the crime.

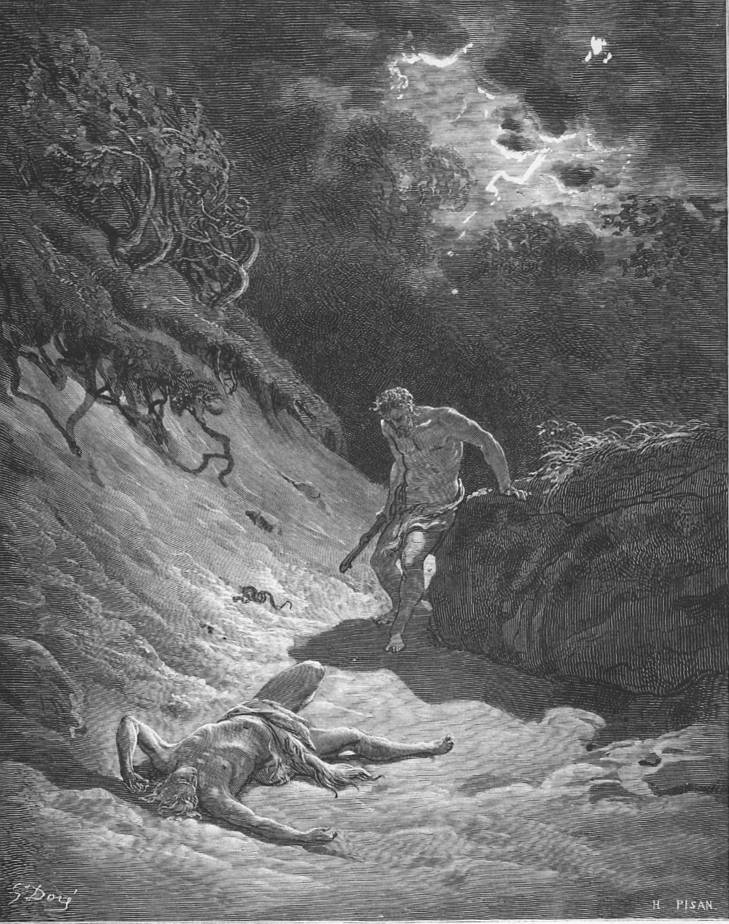

The Death of Abel, 1866, by Gustave Doré (1832-83).

Unlike his parents, Adam and Eve, and his brother Abel, Cain cannot come to terms with his mortality. Cain's rebellion grows out of his disbelief in God's goodness. When Abel asks Cain to join him in sacrifice, they both build altars. Cain's altar is higher and Abel's is lower. A flame of fire rises high from Abel's altar to Heaven, but a whirlwind throws down Cain's altar and Jehovah rejects his offering. At the climax of the play, Cain murders Abel in a fit of jealousy and then realises what death is, but shows no remorse for his deed. Dying, Abel asks God to forgive Cain. Adam and Eve curse Cain and drive him out of their home. Is Cain alone entirely responsible for the murder? Byron does not provide a clear answer, but the reader notices that the poet failed to explain the origin of evil in the world and man's attitude towards it.

In the Christian tradition, Abel was idealised as the first martyr, and his fate foreshadowed the death of Christ. Cain was presented as the embodiment of evil. This tradition continued throughout the Middle Ages and even in the religious spectacles of the Renaissance and Baroque epochs. However, since the Enlightenment, Cain has been viewed with less reluctance, and since the Romantic era, he has even become the idol of artists who themselves rebelled against the established social and political order and the prevailing religion. In Byron's drama, Cain reached the height of rebellion against the Divine order and the authority of God. In this aspect, the firstborn son of Adam and Eve resembles the mythical Prometheus who rebelled against Zeus. Cain is in conflict not only with the real world, with his parents and his younger brother Abel, but above all with the Creator, whom he is unable to understand, and what is more, he rebels against Him. Cain realises to his horror that the two immortal beings, God and Lucifer, are completely devoid of love and compassion. In Lucifer's eyes, God becomes an involuntary tyrant bored with his own solitary, endless existence. Lucifer's view of God leads to the idea of the superiority of creation over its Creator, because humans, God's creatures, can feel compassion and love in a way that the Creator cannot. As a result, God's creativity is not far from destruction, or as Lucifer says: "The Maker — Call him / Which name thou wilt: he makes but to destroy (I.i). Cain comes to a similar conclusion. Perhaps there is something that prevents immortal beings from loving. Adah, Cain's wife-sister, adopts a different attitude. She does not dream of returning to Paradise. She asks him: "Why wilt thou always mourn for Paradise?/ Can we not make another?" (III.i). She wants to live her earthly life as best as possible and, above all, she puts her faith in the power of human love. She believes that the human condition, with all its limitations, can be more satisfying than the apparently higher state of immortality.

It is worth emphasising that John Milton's epic poem Paradise Lost had a significant impact on Cain. For Byron, as for many Romantic poets, the hero of Paradise Lost was Satan, and Cain is partly based on Milton's rebellious hero. Moreover, Cain's vision of the Earth's natural history in Act II is a travesty of the Archangel Michael's depiction in Books XI and XII of Milton's epic poem, which culminate in the expulsion of Adam and Eve from Paradise and the prophecy about the sacrifice of the Son of God. The reaction of critics and readers to the drama was overwhelmingly negative, so much so that Byron, in a letter to John Murray on 3 November 1821, denied that the statements of Lucifer and Cain constituted his personal beliefs. Nevertheless, Byron was accused by some of being the apostle of skepticism and nihilism who tried to destroy faith in God's goodness and subvert traditional Biblical theodicy. The contemporary critics, including Francis Jeffrey in the Edinburgh Review, condemned the play as blasphemous, insulting religious sentiments. Similarly, the Gentleman's Magazine for July-December 1821 described the play as "neither more nor less than a series of wanton libels upon the Supreme Being and His attributes" (Rutherford 219). Byron was fiercely accused by contemporary critics of questioning religious dogmas and offending God. They alleged blasphemy and Manichaeism, blaming the poet for betraying Christian orthodoxy. Although they did not consider him an atheist, because Byron repeatedly emphasised his attachment to faith, they certainly treated him as a heretic. Even Hobhouse, a close friend of Byron, protested against Cain and did not want it published. In turn, William Blake appreciated Byron's iconoclastic drama and in his short play entitled The Ghost of Abel (1822), he recognised the significance of Cain. However, in the opening dedication he asked ambiguously: "Can a Poet doubt the Visions of Jehovah?" Only a few friends and sympathisers spoke in favour of Byron's play. One of them was Percy Bysshe Shelley, the poet's close friend. He was delighted with Byron's eschatological approach and in a letter of January 22, 1822, he called the drama "apocalyptic — it is a revelation never before communicated to man" (Shelley 207). Goethe wrote likewise: "Its beauty is such as we shall not see a second time in the worldí (Goethe 261). Sir Walter Scott called the play "a very grand and tremendous drama," adding that "Byron has certainly matched Milton on his own ground. Some part of the language is bold, and may shock one class of readers, whose tone will be adopted by others out of affectation or envy. But then they must condemn Paradise Lost, if they have a mind to be consistent" (Ball 95).

In the Victorian era, critics mostly continued the earlier negative assessment of Cain as a sacrilegious and blasphemous outburst of Byron's nihilism and provocative freethinking. However, there were a few positive voices about Byron's approach to the Fall. Charlotte Brontë thought the work "magnificent" (Elfenbein 129), although under the influence of critical reviews, she remained reticent about the subversive message of the play. Elizabeth Barrett Browning was a keen admirer of Byron. Her poetic novel written in blank verse, Aurora Leigh (1856), is — as she herself admitted — modelled on Don Juan, but being an early feminist, she made a woman the main character of her epic work. As a young girl, Elizabeth was forbidden to read Byron's scandalous poems. But upon learning of the death of the beloved poet, at the age of 18 she wrote the poem Stanzas on the Death of Lord Byron. In A Drama of Exile (1844), a play which reinterprets the biblical expulsion from Paradise, Browning revised both Milton's Paradise Lost and Byron's Cain (Stone). Earlier she praised Cain in her 1824-1826 notebook when the controversy over this "blasphemous" text was still intense (Stone). Initially Algernon Charles Swinburne wrote appreciatively of Byron in the preface to his Selection From the Works of Lord Byron (1866), although he did not include any fragment from Cain, but when Matthew Arnold placed Byron above Keats and Shelley, and published in his anthology Selected Poems of Lord Byron (1881) two passages from Cain: Cain's journey through the Abyss of Space (II.i) and the scene with his sister-wife Adah (III.i), Swinburne unexpectedly "switched from eloquent appreciation to shrill abuse" (Jump 135). Nevertheless, Byron's works gained more and more recognition in Victorian Britain after the 1870s, thanks to, amongst others, the critic John Ruskin, who described Byron as "the greatest poet after Shakespeare" ("Ruskin and Byron"), and the poet Alfred Austin, who published a Vindication of Lord Byron (1869) in support of his work.

In the twentieth century, Cain's crime was interpreted by Albert Camus in the book-length essay The Rebel (L'Homme révolté, 1951) as a "metaphysical rebellion" (Camus 22), in which man is discontented with his individual fate and the human condition. In Byron's drama, Cain becomes the prototype of a rebel who rejects guilt for uncommitted sins, and also realises the horror and significance of the murder he committed as the first person in the history of mankind. Before Abel, no one had ever died. By showing Cain's moral dilemma, Byron anticipated Albert Camus' existential thought about man's estrangement and alienation in the world. In the novel The Stranger (L'étranger, 1942), the protagonist Meursault lives with similar existential dilemmas to Byron's Cain. They both represent humanity suffering from the senselessness of its existence in a world without a transcendent dimension. Byron was undoubtedly rightly disappointed by the reaction of his contemporaries to Cain, in which he achieved the depth of eschatological reflection. "Cain's story shows more radically than Adam's that the human condition is one of exile and alienation" (Cantor 52). In no other work did the poet raise such fundamental existential problems. Today we would undoubtedly distinguish Byron's Cain as a unique work of timeless value.

Link to Related Material

Bibliography

Austin, Alfred. A Vindication of Lord Byron. London: Chapman and Hall, 1869.

Ball, Margaret. Sir Walter Scott as a Critic of Literature. New York: The Columbia University Press, 1907; available in Project Gutenberg.

Blake, William. The Ghost of Abel, also available in Project Gutenberg.

Byron, George. Cain: A Mystery in: The Works of Lord Byron, Vol. V, Project Gutenberg.

Camus, Albert. The Rebel. New York: Random House, Inc., 1956.

Cantor, Paul A. "Byron's Cain. A Romantic Version of the Fall." The Kenyon Review. New Series, Vol. 2(3) (Summer, 1980): 50-71.

Elfenbein, Andrew. Byron and the Victorians. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

Galt, John. The Life of Lord Byron. New York: J. & J. Harper, 1831.

Goethe, Johann Wolfgang. Conversations of Goethe with Eckerman and Soret. London: George Bell and Sons, 1874.

Jump, John. "A Short Guide to Byron Studies." Critical Survey. Vol. 4(2) (Summer 1969), 134-40.

"Ruskin and Byron" at: https://www.lancaster.ac.uk/fass/ruskin/empi/notes/fbyron02.htm

Rutherford, Andrew, ed. Lord Byron. The Critical Heritage. London and New York: Routledge, 1970.

Shelley, Percy Bysshe. Select Letters of Percy Bysshe Shelley, ed. by Richard Garnett. London: Kegan Paul, 1882.

Stone, Marjorie. "The Scene of Instruction: Romantic Revisionism." The Victorian Web.

Truman Steffan, Lord Byron's Cain: Twelve Essays and a Text with Variants and Annotations. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1968.

Created 25 October 2023