In transcribing the following paragraphs from the Internet Archive online version, I have expanded the abbreviations for easier reading and added paragraphing and subtitle South The illustrations are in the original. The Gazetteer has 1856 on the title-page for this volume, but the statements in this essay date it to 1851. — George P. Landow]

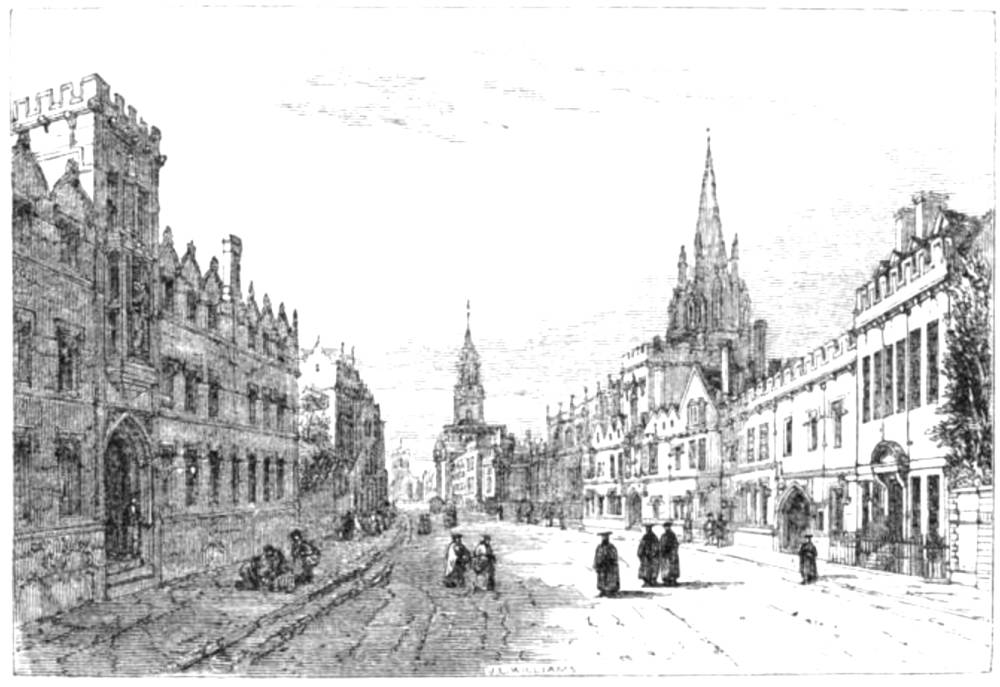

XFORD, a city, England, the capitol of Oxfordshire and seat of one of the most celebrated universities in the world, lies 52 miles West-northwest of London, on a gentle acclivity, between the Cherwell and the Isis, which here unite, and are crossed by several bridges; the principal of which are Folly Bridge, over the Isis, and Magdalene Bridge, over the Cherwell. In early times it was surrounded by walls, considerable portions of which still exist, and defended by a castle; of which the keep, built in the time of Rufus, remains entire, and is in cluded in the precincts of the county jail. It is of a very irregular form, and contains only a few great thoroughfares, with a considerable number of narrow and crooked streets and lanes, especially on the West side, occupied by the lower classes of the population; though considerable improvements have recently taken place. The principal street, called High Street, has a total length of about 1000 yards, and a width not uniform, but where greatest, about 85 ft.; is fronted by several of the noblest structures of the city, and in other parts lined by quaint old houses and elegant modern shops, and is justly regarded as in many respects one of the finest streets in England. The streets in general are well paved, cleaned, and lighted; and water of excellent quality is abun dantly provided.

The University and All Soul’s Colleges; and Churches of St. Mary, All Saints, and Carfax, High Street, Oxford.. Click on image to enlarge it.

Oxford being the see of a bishop, of course possesses a cathedral. It contains also thirteen parochial and three district churches; and has places of worship for Wesleyan and Primitive Methodists, Independents, Baptists, and Roman Catholics. The cathedral, which originally belonged to the priory of St. Fredeswide, and is also the chapel of Christ Church College, is a spacious cruciform structure, inferior to most English cathedrals, and unfortunately situated; its exterior being in a great measure concealed by the college buildings, which partly surround it, but forming on the whole a very fine building, chiefly in the late Norman style.

St. Mary’s, called also the University Church, finely situated on the North side, and nearly in the centre of the High Street, and rendered conspicuous by its richly-decorated tower, terminating in a beautiful spire, 180 feet high, still ranks, notwithstanding the incongruous addition of a porch with twisted pillars given to it by Archbishop Laud, as one of the finest Gothic structures of Oxford. St. Martin’s or Carfax is a modern structure, with an ancient tower, well situated, at the crossing of the four great thoroughfares High Street, Queen Street, St. Aldate’s, and Corn Market, and takes its name of Carfax from the French, Quatre voies [four ways], since corrupted into Carfax; but possesses little architectural merit. St. Mary Magdalene presents several beautiful features, and has lately acquired additional interest from the Martyrs Aisle, which has been added as a fit accompaniment of the Martyrs Memorial; a splendid monumental pile which stands close to it, near the spot where Ridley. Latimer, and Cranmer suffered martyrdom. St. Aldate is chiefly remarkable for its antiquity, and its tower, surmounted by an octagonal spire. St. Giles is chiefly in the early English style, with lancet-shaped win dows, and a square embattled tower. The chapel of Merton College consists of a choir and transept; the latter of which is also the parish church of St John, while the choir is the chapel of the college. This portion, though much disfigured by recent painting, is one of the most beautiful buildings in Oxford; presenting an exquisite example of the geometrical-decorated of the time of Edward I. It was built in 1277. The East window is particularly fine, with a large circle, usually called a Catherine wheel, in the head; the piers of the tower are of the same date, but the tower itself and the tran sept are of 15th century work, but very good. St. Peter-in- tlie-Eaj>t, the most ancient church of Oxford, and originally Norman, though subsequently much altered by additions in the early English and subsequent styles, is surmounted by a square tower; the chancel is Norman, with good detail; and underneath is a fine Norman crypt with a vaulted roof, resting on four ranges of low massive pillars. St. Thomas, originally founded by the canons of Osney Priory in 1141, is surmounted by a square, embattled tower. All Saints , one of the few Oxford churches in which the Gothic style has been abandoned, is a Grecian structure by Aldrich, with a tower terminating in a spire, which rises from within a circlet of Corinthian pillars. Some of the other churches, both district and parochial, are handsome, and might well deserve notice in any other locality where they were not eclipsed by nobler structures. There are likewise three small cemetery chapels lately erected. The Dissenting chapels are neat and commodious buildings, but with exception of that of the Wesleyans in New Inn Hall Lane, and that of the Independents in George Lane, which is a large and handsome Gothic edifice, possess little architectural merit.

The great boast of Oxford is its University, which, though not unrivalled as to the celebrity of its professors, and the completeness of its educational system, stands pre-eminently distinguished by the magnificence of its buildings and the richness of its endowments. The date of its original founda tion is unknown, and it had long existed as an establishment of European celebrity, when it was incorporated by charter of 28 Henry III., A.D. 1244, under the title of the Chancellor, Masters, and Scholars of the University of Oxford. But though thus named as a single body, it does not form one great establishment, contained, as in the case of the Scotch universities, within one enclosure, but consists of a number of separate establishments called colleges and halls, placed under independent management, and occupying not only distinct, but, in some instances, widely distant localities. The colleges are nineteen, and the halls five in number; but they scarcely differ from each other, except in some peculiarities of management, the mode of education being in all essentially the same. They are named as follows:

| Colleges | Heads of Houses. |

| All Souls | Warden |

| Balliol | Principal |

| Christ Church | Dean |

| Corpus Christi | President. |

| Exeter | Rector |

| Jesus | Principal |

| Lincoln | Rector |

| Magdalene | President |

| Merton | Warden |

| New | Warden |

| Oriel | Provost |

| Pembroke | Master |

| Queen’s | Provost |

| St. John’s | President |

| Trinity | President |

| University | Master |

| Wadham | Warden |

| Worchester | Provost |

| Halls | Heads of Houses. |

| Alban | Principal |

| Edmund | Principal |

| Magdelene | Principal |

| Mew Inn | Principal |

| New Inn | Principal |

| St. Mary | Principal |

In St. Aldate’s is Christ Church College, the largest and grandest of the whole, occupying an extensive range of buildings, in the form of three quadrangles, and communicating the South and East with verdant meadows, and a wide walk, called the Broad Walk, overshadowed with lofty elms, planted in the time of Charles II., which is used both by colle gians and citizens as their favourite promenade. The front along the street has a length of 400 ft., and has, in its centre, a magnificent gateway, begun by Cardinal Wolsey, and completed after the design of Sir Christopher Wren; it is in the form of a circular tower, crowned with a dome, and con tains the famous bell known by the name of the Great Tom of Oxford, measuring 7 feet 1 inch in width, 5 feet 9 inches in depth, and weighing nearly 8 tons. Directly opposite is Pembroke College, with a small, elegant Ionic chapel, adorned with a beautiful altar-piece.

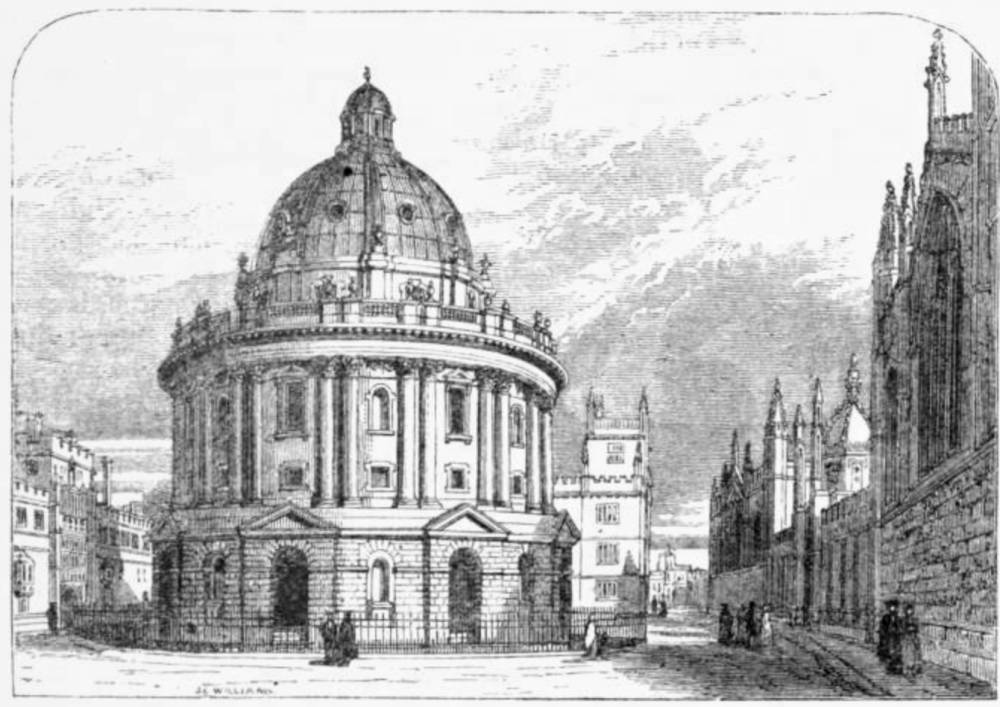

Immediately East of Christ Church are the colleges of Oriel and Corpus Christi; the former possessing in its library a building of the Ionic order, which, though unfortunately situated, is regarded as one of the most perfect pieces of architecture in Oxford; and the latter entered under a square tower, with rich canopied niches, and containing, over the altar of its chapel, a fine painting of the Adoration of the Magi, by Rubens. Still farther East are Merton College and Alban Hall; the former, consisting of two quadrangles, entered under an ancient embattled tower, and chiefly remark able for its chapel, which has already been referred to as the parish church of St. John. University College, said to have been originally founded by Alfred the Great, occupies an ex tensive range of buildings, with a front of 200 feet along the South side of High Street; the present buildings are of late date. On the same side of High Street, but at some distance West, is St. Mary Hall, consisting partly of antiquated, and partly of new buildings. On the North side of High Street, and irarly opposite to University, is Queen’s College; so called after Philippa, queen of Edward 1III., consisting of two spacious quadrangles, with one front to the street, containing a central gateway, crowned with an open cupola, enclosing a statue of Queen Caroline, wife of George II. On the same side, and near its centre, close to St. Mary s Church, is All Souls College, consisting of an old and a new quadrangle; the latter partly occupied by a magnificent library. The chapel of this college is much admired for the beautiful simplicity of its decoration, and the imposing effect produced by its general appearance. Near to Queen’s, but a little North, is New-College, founded and built by William of Wykeham, in the time of Edward III. It is a good specimen of the perpendicular, consisting of a large pile of buildings; among which special notice is due to the chapel, which, though stripped of much of the gorgeous decoration, still holds a first place among the sacred edifices of the university. The tower and cloisters are also very fine. The garden of this college, beautifully laid-out, and interspersed with majestic trees, furnishes a most delightful retirement. North of High Street is a cluster of four nearly-contiguous colleges Brazen-Nose, Lincoln, Exeter, and Jesus. Brazen-Nose has a good 15th century gateway tower, hut the rest of the buildings are of a very late and mixed style; Exeter and Lincoln have been, in great part rebuilt. Further North is Balliol College; so called after its founder, John Balliol, father of the Balliol who figures in Scottish history, and remarkable chiefly for its fine Gothic gate. To the North of Balliol is Trinity College, entered under an elegant modern square tower, embellished with pilasters, and surrounded on the top with a handsome balustrade. The buildings are arranged in two courts, and are mostly modern; but little of the original structures remain; the garden front is a picturesque mixture of the renaissance and Gothic. Still farther North is St. John’s College, much admired, both for the elegance of its buildings, partly constructed from a design of Inigo Jones, at the expense of Archbishop Laud, and for the beauty of its gardens. The colleges already mentioned, though covering a large area, are more or less contiguous, and arranged in clusters; the others are more insulated. They are Wadham College, on the North side; Worcester College, near one extremity, in the Northwest; and Magdalene College, at the nearly opposite extremity, in the Southeast Wadham presents in its buildings, arranged in an extensive quadrangle, a very pleasing example of the later perpendi cular style, consisting partly of a lofty hall, lighted by painted glass, and a spacious and well-proportioned chapel, with a beautiful East window, by Bernard Van Linge. Worcester is remarkable chiefly for its pleasant and retired situation, and beautiful gardens; while Magdalene, placed so as to form a conspicuous object in entering the city by the London road, is distinguished alike by the fine cloister of its great quadrangle, the chaste and elegant decorations of its chapel, and the extent and beauty of its meadows, gardens, and walks; but chiefly by the tower, an exquisite specimen of rather late perpendicular, and one of the most gracefully-proportioned buildings in the kingdom.

Besides the buildings of each individual college and hall, five others of an equally, and even more magnificent description, belonging to all in common, or to the university properly so called. Of these the most important are the Theatre, built by Sir Christopher Wren, and used by the university on great public occasions, and, though only 80 feet long by 70 feet broad, so arranged as to accommodate nearly 4000 persons; the Schools, used for the examination of candidates for degrees, and similar purposes, and consisting of a handsome quadrangle, of late or debased Gothic, the buildings of which partly form a picture-gallery, and partly accommodate the rich treasures of the Bodleian Library, which occupies one side of the quadrangle; the Ashmolean Museum, which, though neither in extent nor value to what might betxpected in such a locality, is remarkable as being the earliest public museum established in this kingdom, and as containing the collections of the Tradescants, Elias Ashmole, &c.; the Radcliffe Library, a splendid structure, crowned by a dome, which forms a conspicuous feature in every view of Oxford, and contrasts somewhat strangely, though not unpleasantly, with the Gothic edifices around it; the Radcliffe Observatory, consisting of wings and a light and elegant centre, surmounted by a tower, in imitation of the Temple of the Winds at Athens; the Clarendon, originally built as a printing-office for Lord Clarendon’s works, but now used as a geological museum, lecture-rooms, and public offices; University Printing- Office, a very extensive building by Blore; and the Taylor and Randolph Institution, a magnificent range of buildings by Cockerell, recently completed, partly for the custody and exhibition of works of art, and partly as a foundation for the teaching of modern languages. In connection with the University may be mentioned the Botanic Garden, probably the oldest, but by no means one of the best, in the kingdom; but lately much improved, and enriched with the extensive Fielding Herbarium, in addition to the valuable collections before possessed.

The buildings and establishments in Oxford, not connected with the university, nor yet referred to, but deserving of notice, are the townhall, a spacious stone building, with a basement of rustic-work, used for municipal purposes; nume rous parochial, national, and other schools; the Radeliffe in firmary; the lunatic asylum, founded by Dr. Radeliffe, stands on Headington Hill, more than a mile out of the town; town and county jails, the house of industry, &c. Oxford depends almost entirely on the University, and has no manufactures worthy of mention. In corn, sent into it from the surround ing districts, a considerable trade is carried on; and, for the general purposes of transport, great facilities are afforded by the river, and the Oxford canal; and by the Great Western, a branch of the London and North- Western, and the Oxford, Worcester, and Wolverhampton railways.

Oxford is supposed to be an abbreviation of Oxenford; a name said to have been originally given to the town in con sequence of the existence of a ford for cattle over the Isis, in its immediate vicinity. The date of its origin cannot be determined. A nunnery appears to have been founded in it early in the 8th century, and in 802 an act of confirmation by Pope Martin II. describes it as an ancient seat of learning. It suffered much from the ravages of the Danes; but re covered under the fostering care of King Alfred, who often made it his residence, coined money in it, and added liberally to its privileges and endowments. Parliament re peatedly met in it during the reign of Canute; and his son and successor, Harold Harefoot, was crowned and died at it. At the Norman conquest, on its refusal to submit, William took it by storm, and gave it to Robert de Oilli or d Oiley, who, to insure its submission, both built a strong castle on its W. side, and enclosed it by earthen ramparts; the keep of which, as mentioned before, still remains. In 1142 the Empress Maud, having taken refuge in the castle, was besieged by Stephen, and ultimately escaped with only three attendants. The council which terminated this civil war, by an agreement between Stephen and Henry II., was held here; and various other parliaments were held in subsequent reigns. The discussions occasioned by the doctrines of Wickliffe were carried on with such keenness within the university, as almost to threaten its destruction; but at last, when the Reformation was on the eve of becoming triumphant, Oxford, which had previously been included in the diocese of Lincoln, was converted by Henry VIII. into a separate see. On the accession of Mary it was made the scene of some of her worst atrocities; and Latimer, Ridley, and Cranmer, were here consigned to the flames; the first two in October, 1555, and the last in March of the following year. During the last great civil war, Oxford became the headquarters of the king; and having dis played great zeal in his cause, was so severely handled by the Parliamentarians and the Commonwealth, that it scarcely ventured to lift its head till the Restoration. Oxford claims to be a borough by prescription, and is governed by a mayor, nine aldermen, and thirty councillors; but the members of the and university are exempted from their jurisdiction. Both the borough and the university send each two members to Parliament. Pop. (1851), 27,973. [III, 555-57]

The Radcliffe library. and All Souls’s and Brazen-Nose Colleges, Oxford. Click on image to enlarge it.

Bibliography

Blackie, Walker Graham. The Imperial Gazetteer: A General Dictionary of Geography, Physical, Political, Statistical and Descriptive. 4 vol South London: Blackie & Son, 1856. Internet Archive online version of a copy in the University of California Library. Web. 15 November 2018.

Last modified 15 November 2018