This article has been transcribed from a copy of the Cardiff Times in the online collection of scanned Welsh newspapers 1804-1919 in the National Library of Wales, with grateful recognition of the free access accorded to all readers. Paragraph breaks have been introduced for easier reading.

The pictorial capital introduces a note of political topicality not found in the text. Bradford was the centre of the woollen industry, and the labour disputes there would be a major factor in the foundation of the Independent Labour Party in 1891. Cheap labour available to its German competitors was often blamed for the decline of the industry in Yorkshire. German industry, which had profited from the Prussian annexation of Alsace in the Franco-Prussian War, had mechanised more recently and more efficiently than that in England, which was slow in responding to workers’ demands about pay and conditions. (For years there was a failure to tackle ‘woolcombers’ disease’, a type of anthrax contracted from unsterilised sheep’s wool.) The presence of the ‘German professor’ is a sign that British universities had fallen behind their Continental counterparts in the pursuit of economics. This is the word in which the Second International was soon to be founded. The songs and recitations listed are a world away from the serious business of life. Focusing on his own social insecurity, Samuel may not be aware of this, but the editor of the Cardiff Times almost certainly is.

The songs and recitation piece are:‘ Rocked in the Cradle of the Deep’ by American women’s rights activist, Emma Hart Willard (1787-1870) to music by J. P. Knight (1812-87); ‘The Diver’: words by G. D. Thompson, (1865); music by E. J Loder (1809–65); ‘Holy Friar’, words by John O'Keeffe (1747-1833), music by D. W. Reeves (1835-1900); ‘The Death of Nelson’ by Samuel James Arnold (1774-1852), set by John Braham (1774-1856); Tennyson’s ‘Come into the garden, Maud’, best known in the setting by M. W. Balfe (1808-70); clicking on this link will allow you to hear the song performed; Thomas Hood’s ‘The Dream of Eugene Aram’, about the philologist and infamous murderer; and the ballad ‘Fine Old English Gentleman’ set by Henry Russell (1812-1900). —David Skilton

The ‘professor’ who is always in evidence at evening parties – especially in Bradford. ‘German Cheap Labour.’

MORTALLY detest evening parties, sir -- and especially have I always hated those where it has been my misfortune (in my bachelor days, of course) to arrive in the character of the first man who turned up, and had to confront half[-]a-dozen ladies or more of varying ages and different types who had previously arrived on the dismal scene. That was a caution, you bet. I break out into a cold perspiration every time I think of it. Most of the ladies usually were, by a horrid concatenation of circumstances, complete strangers to me, and I felt painfully conscious that many a pair of disparaging eyes was bent upon me as I painfully sat down on the very extreme edge of a very low arm chair, into which I flopped, feeling as though I were going down a precipice. My hands suddenly seemed to turn very red and ‘beefy,’ and twenty times their natural size; my feet appeared to have an inclination to retire shyly somewhere out of view under my body; and when I at length mustered up courage to open my mouth to make some original remark pertaining to the weather, I seemed never to have heard my own voice before, so strange and hollow did it sound, and I felt dreadfully conscious of the fact that, once the subject of the weather should be exhausted, I had literally nothing whatever in the nature of topics of ‘widespread interest'’ (as the book advertisements say) to go on with. And the awful thought assailed me that in that mixed congregation of women, all staring at me, I might quite inadvertently tread upon some theme likely to be distasteful to one or other of them, or that I might say something which one of them might think contained a personal reference of an unamiable kind. Possibly you may have suffered all this, my dear sir; if so, you can sympathise with me

This the only sort of being who can make an evening party endurable.

But I must confess that this feeling wears off after a time, and if the host or hostess does not happen to have introduced one as a ‘funny man’ (a course which entails awful torture on a guest) or as a bachelor on the look out for a life partner (a rude act which covers one with terrible confusion), one begins to get on with tolerable comfort, considering the circumstances. It is true that one is generally much discomfited by meeting some fellow whom one most particularly detests, or some other fellow who happens to know something particularly funny about one. In the former case a mutual glare usually follows the first greeting, and it becomes evident that throughout the meeting there will be hard ‘snacking’ [sharp remarks] of a polite kind going on; in the latter case I myself was always on pins and needles throughout the evening, lest the man who knew such a lot should deign to air his wit for the amusement of my fellow guests. It is somewhat strange that should this man actually tell his story, the glorious retort that one ought to make to turn the tables on him always occurs to a fellow a day or two afterwards, when it is not a bit of good – at least, it has always been so with me.

‘Strange that I should forget the words. T s – s – s – t , dear, dear me!’

I verily believe that persistent social nuisances are the very people who are most invited out to evening parties. Think of the vocalism (Oh, corkscrews, and teeth on edge!) usually prevalent at them. Just think of the very little, wizened number seven basso, with the number seventeen beard, who growls out ‘Rocked in the Cradle of the Deep’ and ‘The Diver’ (how one does wish that he'd dive and never come up any more), and a few other things one has never heard before; think (and patiently if you can) of the baritone (probably a regular ‘roarer,’ as racing men say) who shouts out the ’Holy Friar’with a fearful lot of ‘Ho-o-o-o-o-o oh’ about the run in it; try and reflect charitably on the ‘Death or Nelson’ (nearly the death of everyone else cum ‘Come into the garden, Maud’ tenor, if you can. That ‘Maud,’ with her everlasting obstinacy in not complying with the request so frequently, yet politely, made to her, has much to answer for, but probably the lady fears that she may get her feet wet. Then let your thoughts dwell upon the angular women who play a pyrotechnic duet together, the girl who howls ‘I'll follow thee’ (awful thought) with all the trills in it; the tragical ‘comic’ vocalist who mugs and mouths, and at whom no one laughs except perhaps the most juvenile member of the party, who has been permitted, poor child, to remain up a little longer than usual, and who expresses an opinion that Mr Comic-song-man is ‘such a silly, to act being off his head like that’ -- let your mind dwell, I say, upon these people. and then go out and order your coffin, or inquire upon what terms they are prepared to receive you at the nearest lunatic asylum.

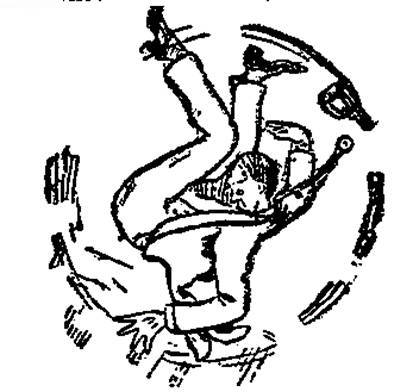

This illustrates the queer sort of thing that may occur as a consequence of dancing on a well bees-waxed floor.

There will probably, to add to the other horrors of the evening, be a lady with red hair who performs on the violin, and who makes you writhe like a corkscrew, a young man of unwholesome aspect, with long hair, who groans, gasps, poses, and attitudinises as a reciter of ‘Eugene Aram's Dream’ (or some other totally unfamiliar selection), during the delivery of which he pulls himself a good deal to pieces in the region of the collar and necktie — these people are nearly certain to be there, and if there should happen to be present an amateur conjuror who borrows handkerchiefs, watches, and money, and does tricks that you could see much better done for a copper or two in a show, your cup of wretchedness may be supposed to be full to overflowing, especially if the weak-witted wizard should happen to fancy that he is a ‘good natterer,’ and should consequently attempt to inflict upon you certain of his ‘wheezes with whiskers on.’

Samuels’ notion of spending a quiet evening. Bother parties; let’s light up and be happy.

But these undesirable members of long-suffering society are generally, sir, to be found in full force at the average evening party, and they are supplemented by pleasing people who propose conundrums, and then either suddenly find that they have not asked them properly or that they have forgotten the answers; mammas who regard you with a meaning and an interested eye if you should happen to pay rather more than usual attention to one of their daughters; old gentlemen who volunteer just one song, and oblige with the ‘Fine Old English Gentleman;’ envious people who, as you can see when you catch their eye, are disparaging you amongst themselves, and people who seriously go to eat when supper is one of the features of the entertainment, and these are perhaps the wisest folks of all. I have not spoken, sir, of the phases of an evening party when dancing is provided, but I am thoroughly acquainted with the blasé young man who never ‘darnces, you know;’ the ugly man who scowls at his pretty wife (it's funny how nearly all the ugliest men get the bonniest wives -- but they do) because she has happened to dance twice with one man; the other husband who has palpably had a misunderstanding with his wife, and who, with an air of meaning, dances wildly with all the pretty girls who will put him down on their cards; the young man whose socks come down over his patent leather shoes; the damsel who loses her slipper, which flies in the eye of a gentleman, who, half blinded with pain, and not seeing who is the author of the trouble, gives way to an impulsive ejaculation of a sultry sort; the nervous young man who falls heavily and in a complicated fashion during a quadrille; the red-faced, jolly man who has evidently been taking too much refreshment and who beams insanely on everyone present, and the very little fat man who bounces all round the room like a cork, threatening destruction to everyone who may come near him. Then there are always to be found the -- oh, hang evening parties; give me a glowing hearth, the curtains drawn, two or three jovial men of the world, right good Bohemians, the pipe which sootheth, the liquor which comforteth, and the good judgment to take of the latter sparingly.

Last modified 18 February 2022