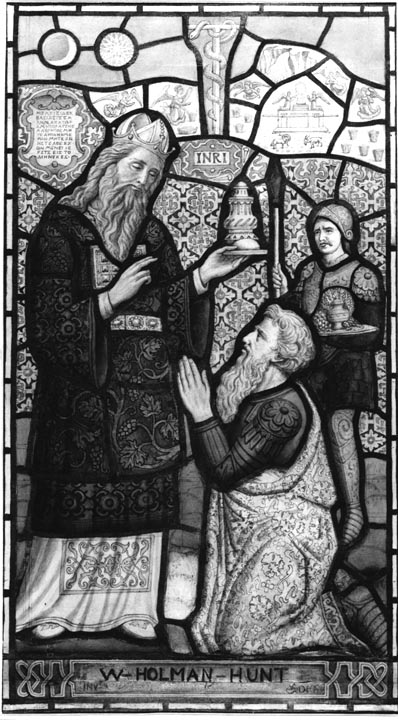

Hunt made a far different use of typological symbolism in Melchizedek,

a design for a stained-glass window, a pen and wash drawing of which is in the British Museum Print Room. The origins of this undated design are unclear, although it is possible that the artist began it in 1865 for the Rev. W. J. Beamont, who had been appointed vicar of the Church of St. Michael and All Angels, Cambridge, in that year. Pre-Raphaelitism and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood relates that Beamont asked him to decorate his church, but it does not mention any stained-glass designs, and Melchizedek does not seem to fit in with the paintings Hunt proposed to execute (II.250-2). Whatever its origins, this work is of particular interest, because the nature of stained-glass precluded Hunt's characteristic use of a realistic assemblage of symbolic details. Instead, the artist chose to contrast his chief subject, the encounter of Melchizedek and Abram, with a series of symbols in the upper portion of the window.

Hunt made a far different use of typological symbolism in Melchizedek,

a design for a stained-glass window, a pen and wash drawing of which is in the British Museum Print Room. The origins of this undated design are unclear, although it is possible that the artist began it in 1865 for the Rev. W. J. Beamont, who had been appointed vicar of the Church of St. Michael and All Angels, Cambridge, in that year. Pre-Raphaelitism and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood relates that Beamont asked him to decorate his church, but it does not mention any stained-glass designs, and Melchizedek does not seem to fit in with the paintings Hunt proposed to execute (II.250-2). Whatever its origins, this work is of particular interest, because the nature of stained-glass precluded Hunt's characteristic use of a realistic assemblage of symbolic details. Instead, the artist chose to contrast his chief subject, the encounter of Melchizedek and Abram, with a series of symbols in the upper portion of the window.

Above the figure of Melchizedek, the just king, Hunt provided a Greek inscription which is a conflation of Hebrews 7:1 and 3: "Melchizedek, king of Salem, who has neither a beginning to his days, nor an end to his life, remains as priest forever." (I am grateful to Professor Ernest S. Frerichs for identifying and translating this inscription for me.) This king of Salem, who appears briefly in Genesis 14, received his great importance as type in the Epistle to the Hebrews, where the apostle insists that Christ will be "made an High Priest for ever after the order of Melchisedek" (6:20) rather than that of Aaron. As the Rev. James Brown, a Victorian interpreter, explained in the 1881 Good Words, little is known of the just king, except that "amid the increasing lawlessness of an evil time this Canaanite chief seems to have recognised the righteous law of God, and to have so regulated his conduct and ruled his tribe in obedience to that law, as to have for himself the name of Melchizedek, or King of Righteousness" (442-45). He refused to take part in the various wars of conquest then being fought, and his city was called Salem, or Peace. although he did not involve himself in the wars of his neighbors, he did not stand apart from their troubles, "and when any were passing that way who were wounded and weary, he would go forth with bread and wine to bless them". According to Brown, "it is because Melchizedek thus attained to priestly influence, through no sacerdotal descent and by no official consecration, but by the simple power of his righteous, peaceful, and brotherly life, that a Hebrew psalmist and a Christian apostle unite in recognizing the true type or similitude of the priesthood of Christ, not in the sons of Aaron, who ministered in the pompous ceremonial of the Jewish temple, but in this sheikh of a Canaanite village". In words which Hunt himself might have voiced, the preacher emphasized that so "repugnant" to those who love "officialism" is this glorification of a humble, righteous man, that some have sought to make him in some way of miraculous descent, as though only

something superhuman, or at least preternatural, could be a type of Christ, Who Himself was a poor Galilean peasant . . . It is because there is thus nothing artificial in Melchizedek's priesthood, nothing which does not essentially belong to every priestly life, that it is recognised as the truest type — not a mere "shadow" like the legal types, but a veritable "image" or "similitude" of the highest priesthood . . . So Christ brings God near to us in His words by which He has revealed the Father; but, like Melchizedek, He has not loved in word, neither in tongue, but in deed and in truth; He has made sacrifice for us. Melchizedek made sacrifice of bread and wine. Christ has sacrificed Himself.

In addition, this righteous king prefigures the true priesthood not only by blessing and physically assisting Abram but also by claiming a tithe of this spoils for God.

Such a conception of this just man and his relation to Christ is completely in keeping with Hunt's own beliefs. In particular, his dislike for the "officialism" of the Church hierarchy led him to this conception of true priesthood and holiness. The Shadow of Death, which emphasizes the humble nature of Christ's daily existence as a laborer, is in accord with a belief that the humble Melchizedek stands as a true type of Christ, a point enforced by the typological imagery in the upper portion of the design.

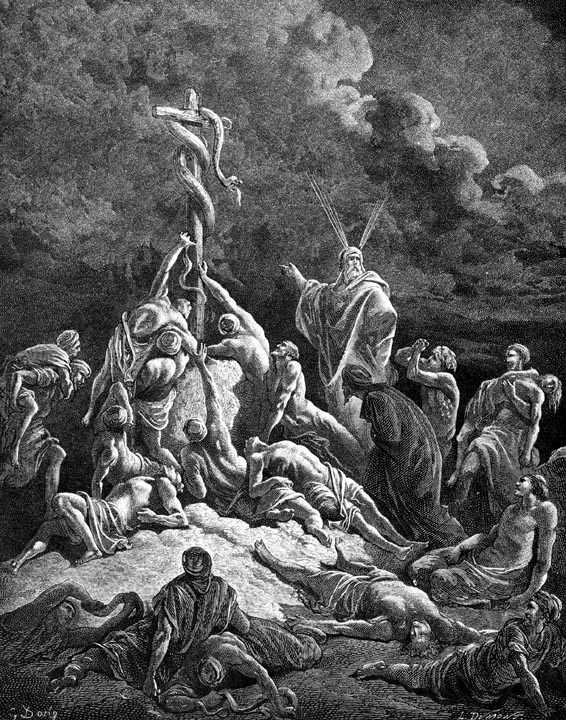

The Brazen Serpent

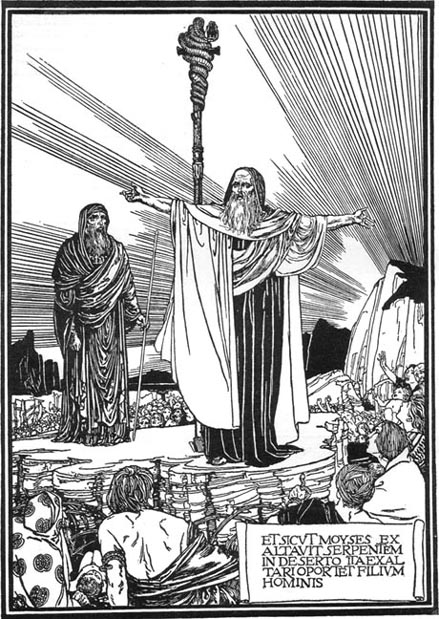

Two depictions of the brazen serpent, that on the left by Gustave Doré and the one on the right by William Butterfield. Click on the images to enlarge them.

At the center Hunt has placed the commonplace type of the brazen serpent, which comments upon the action taking place beneath. During the Exodus poisonous snakes were sent among the Jews, and Moses was commanded to make a brazen serpent and set it upon a pole before the eyes of his followers, instructing them that if they contemplated this image with faith, God would heal them. Because the T-shaped pole resembles a cross, this episode from Exodus was understood to prefigure the Crucifixion, for Christ's sacrifice of himself upon the Cross saves men from the serpent Satan — if they contemplate it with the eves of faith.

Left: The Brazen Serpent by Robert Anning Bell. 1919. Right: The Brazen Serpent by P. Ball. From “Royal Academy Prize Designs,” Illustrated London News 48 (January 1848): 28.

Some Victorian exegetes, like W. H. Lyttelton, also held that, since men were instructed to contemplate this image in the midst of extreme suffering, it had an additional meaning as well, for it was "simply a call to face God's terrible dispensation in faith and submission" (188). Such an interpretation of the brazen serpent is appropriate to the scene of Melchizedek and Abram, which followed a period of great trial for their peoples.

Another commonplace type, taken as a prefiguration of Christ's sustaining grace, appears in water pouring out of a cloven rock . When the Jews of the Exodus suffered from extreme thirst, God commanded Moses to strike a rock in Horeb, from which immediately flowed a fountain of life-giving water. Like the brazen serpent from Numbers 21:4-9, the stricken rock in Exodus 17:3-6 provides a type of Christ which comments upon the central action in the design, for both concern the nature of prayer as well as the saving power of Christ. The type of Moses striking the rock, which appears in the earliest Christian art, was interpreted in various ways. It was understood to demonstrate that the Old Law of Moses would have to strike — crucify — Christ for his grace to flow forth; it was taken as a literal prefiguration of the water and blood which flowed from Christ's side at the Crucifixion; it was interpreted as a symbol of baptism and as a parallel to the manna, which was a type of the Eucharistic bread; and it was read as an indication of the way that Christ's grace wrung repentant emotion from the worshipper's stony heart. Traditionally the rock in the absence of Moses signifies the way Christ physically and spiritually sustains the believer — an echo of Melchizedek succoring Abram.

Two examples of the stricken rock. Left to right: (a) The Israelites drink from the water that flowed from the rock by Gustave Doré (note Moses in the background). (b) Moses striking the rock by Joseph Durham.

The five panels containing angels and bushels presumably are images of the manna from Exodus 16, which provides a parallel type of that of the stricken rock. In contrast, the relatively large panel representing the Ark of the Covenant, like those with the sun and moon, comments differently upon the relation of old and new. Whereas all the typological emblems we have thus far examined in Melchizedek emphasize the continuity from Judaic to Christian dispensations, this panel introduces the element of opposition between them. In the main part of the window Abram and the just king perform their sacrifices and worship God, each in accordance with his role. The image of the Ark echoes this notion of religious sacrifice in the presence of God, but the paired animals — the Old Testament sacrificial goat and the New Testament Lamb of God — contrast physical and spiritual, literal and symbolical, partial and complete. To retain the presence of the Lord the ancient Jews had to live as best they could according to the moral law, and when they failed to meet its standards, they sacrificed animals to receive mercy. Christ's greater sacrifice, which is symbolized by the three nails and the panel containing "INRI," replaces this Old Law, for his blood obviates the need for such inferior sacrifices.

More then any of his other works, this stained-glass design resembles an emblem by Ripa or one of the other participants in this emblematic iconographical tradition. The ancillary types do not interact "realistically". They do not arise as naturally occurring details of the main scene, and Hunt does not even attempt to place them in the same "space" as the encounter between Abram and Melchizedek.

Whereas these Old Testament figures meet against a decorative background, the prefigurative emblems appear in the clear panels above, making it clear that they exist in some other realm. His little known design for stained-glass is particularly instructive to the student of Hunt's iconography, because it shows how closely related to the medium of oil-painting was his usual application of typology to sacred history. In stained-glass, which prevents the creation of a more naturalistic image, he employed by necessity an essentially heraldic design. Still wishing to produce a meditative image, he depended almost entirely on the juxtaposition of explicit symbols rather than their incorporation into a realistically conceived event. This kind of schematic juxtaposition of symbolic elements may always have been potential in Hunt's work, but his oil-painting restricts such schematic iconography to the frame.

Created December 2001; last modified 29 October 2020