Left: Andromeda. 1872. Oil on canvas, 501/2 x 21 inches (128.3 x 53 cm). Private collection.Right: Andromeda. c. 1872. Oil on paper laid down on panel, 491/2 x 201/8 inches (125.7 x 51.3 cm).[Click on images to enlarge them.]

he story of Perseus and Andromeda comes from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Book 4, although Stanhope would also have known the story from William Morris’s poem “The Doom of King Acrisius” from The Earthly Paradise. Andromeda was the daughter of King Cepheus of Aethiopia. Her mother Queen Cassiopeia angered the god Poseidon by claiming that Andromeda was more beautiful than the Nereids. Poseidon therefore sent a sea monster to devastate Cepheus’s kingdom. In order to appease the sea god Andromeda was condemned to be chained to rocks on the seashore and left as a sacrifice to the sea-monster. Perseus, the son of Jupiter by Danaë, saw her predicament when he happened to be flying overhead on the winged horse Pegasus. Perseus turned the fearsome sea creature to stone using the magic of the severed head of the Gorgon Medusa. Perseus was granted Andromeda’s hand in marriage as a reward for saving her.

Stanhope painted an additional version of this work in addition to the one he exhibited at the Dudley Gallery in 1872. The second version was virtually the same size but the background features are quite different. The second composition features the sea only to the left with Andromeda standing on a more enclosed and rocky promontory and bound by cords rather than being chained to a post with open sky above her. More red, pink, and white roses are strewn at her feet in the second version. It was not uncommon for Stanhope to paint two versions of the same subject, possibly creating one on commission and another to retain for himself or as a second commission.

Left: Sandro Botticelli. Pallas and the Centaur. c.1480-85. Tempera on canvas. 81 ½ x 58 ¼ inches Right: Sandro Botticelli. The Birth of Venus. c.1485. Tempera on canvas, 68 x 1095/8 inches (172.5 x 278.5 cm). Collection of Uffizi Gallery, Florence, inventory no. 1890 n.878. click on image to enlarge it. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Andromeda owes a debt to the work of Sandro Botticelli, with the pose of her figure, the flowing hair, and the position of the arms all influenced by Venus in The Birth of Venus. The rocky architecture of the second version of Andromeda draws heavily on that seen in Botticelli’s Pallas and the Centaur. Both of Botticelli’s pictures were in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence so Stanhope would have been very familiar with them.

Other Victorian Paintings of Perseus and Andromeda

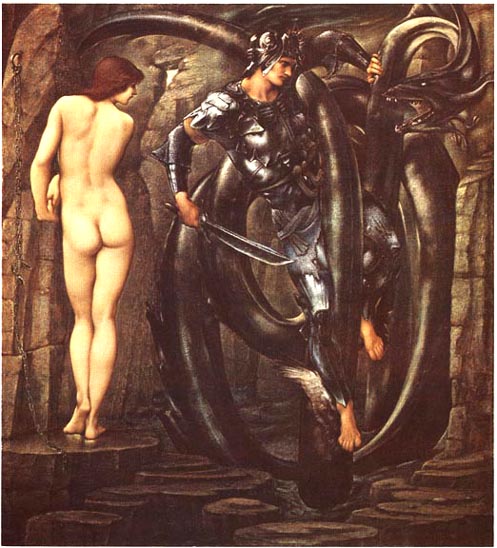

The subject of Perseus and Andromeda was a popular one in Victorian art. Stanhope's mentor G. F. Watts, as well as his friends Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones, designed ambitious paintings depicting Andromeda. In the 1860s Rossetti made many drawings for his composition Aspecta Medusa, but a finished painting never materialized. Burne-Jones painted an ambitious series of pictures depicting the story of Perseus and Andromeda, which portrayed Andromeda bound to the rocks in two of these pictures, The Rock of Doom and The Doom Fulfilled, now both in the Staatsgalerie in Stuttgart.

Left: Aspecta Medusa. Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882). Signed with a monogram and dated and dated 1867 at the upper right. Coloured Chalks; the sheet was extended at the lower edge. 22 x 20 ½ inches. Middle: The Rock of Doom. Right: The Doom Fulfilled. Both Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones, Bt ARA (1833-1898). Oil on canvas. Staatsgallerie Stuttgart [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Andromeda. Sir Edward John Poynter, PRA RWS 1869. Oil on canvas, 152.4 x 114.2 cm. Pérez Simón Collection, Mexico. Photograph © Studio Sébert reproduced here by kind permission of the Leighton House Museum.

Frederic Leighton painted Andromeda about to be rescued by Perseus in his Perseus and Andromeda of 1891 at the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool. Edward Poynter included this subject as one of the decorations he painted for Lord Wharncliffe's billiard room at Wortley Hall in Yorkshire. Poynter also painted a single-figure composition of Andromeda in 1869 that he exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1870 and subsequently showed his painting of Perseus and Andromeda at the Royal Academy in 1872.

In 1872 Stanhope showed a small sculptural relief of Andromeda at the Royal Academy, the only sculpture he ever exhibited. The reviewer for The Saturday Review felt the sculpture showed “real grace and beauty” (20). This myth also influenced the New Sculpture movement with statuettes of Perseus by both Alfred Gilbert and F. W. Pomeroy proving popular. According to Poë the model for Andromeda in Stanhope’s paintings was once again Maria Zambaco. Poë contrasts her with the ethereal beauty of the model chosen by Burne-Jones for his Andromeda whereas Stanhope’s “model for the figure of Andromeda exhibits none of the perfection of form boasted by Burne-Jones’s…She has rather small breasts and quite heavy legs, but there is something rather engaging about her imperfections. She is almost homely and quite unintimidating” (79).

The Painting’s Reception

F. G. Stephens in The Athenaeum for once praised not only Stanhope’s colour but also his draughtsmanship:

Mr. J. R. S. Stanhope’s Andromeda (283) has many noble qualities, with the comparatively rare characteristic of combining intense realism with an antique subject. Andromeda, waiting the coming of the monster, is standing, naked and quiescent, chained to the rock. The picture is remarkable for the delicacy and elaboration of its drawing and modelling; the effect and colour are those of ‘indoors,’ – the colour of itself, is admirable. We do not understand the nature of the dark-brown shadow which accompanies the outline of Andromeda’s left hip. [569]

The critic for The Saturday Review felt this painting lacked passion and for once a reviewer failed to praise Stanhope’s colour: “Very different is the plight of ‘Andromeda’ (283), immobile as a statue, colourless as a marble. Titian was certainly not at the elbow of Mr. Stanhope when this sublime negation was modelled.” Nonetheless, this reviewer thought ”this cold study from the nude inspires respect, though scarcely admiration. A Venetian painter, had he been present in the studio, might have suggested some indirect appeal to passion; but Mr. Stanhope, being left to his own purer promptings, has made his work perfectly passionless; the appeal is the dry intellect. This artist seldom indeed permits himself the enjoyment of beauty – not even the ‘intellectual beauty’ of Shelley. And yet he treads in high paths, and labours as if a duty were laid upon him to carry art into regions of ideal thought’ (600).

Bibliography

Poë, Simon: “Roddy, Maria, and Ned (And Georgie, Topsy, Janey, and Gabriel): An Entanglement.” The Journal of Pre-Raphaelite Studies New Series 9 (Fall 2000) 69-87.

“Sculpture in the Academy.” The Saturday Review 34 (July 6, 1872): 19-20.

Stephens, Frederic George. “The Winter Exhibition of Cabinet Pictures in Oil, Dudley Gallery.” The Athenaeum No. 2349 (November 2, 1872): 568-69.

Trippi, Peter B. “John Roddam Spencer-Stanhope. The Early Years of a Second Generation Pre-Raphaelite 1858-73.” M.A. Thesis. Courtauld Institute of Art, University of London, 1993.

“Winter Exhibitions. Dudley Gallery.” The Saturday Review 34 (November 9, 1872): 600-01.

Last modified 8 May 2022