lizabeth Siddall (1829–62) is well-known to admirers of the Pre-Raphaelites and is often viewed as an important player in their turbulent history. Her fame is largely based on her face: she modelled for J. E. Millais’s Ophelia of 1852 (Tate Britain, London), famously posing in a tub with the water heated by candles, and she reappears in intimate drawings by her companion Dante Gabriel Rossetti, whom she married, in final recognition of their long-standing relationship, in 1860. ‘The Sid’, as Rossetti and his colleagues liked to call her, was the original ‘stunner’, the Pre-Raphaelite ‘Supermodel’ above all others whose looks define ‘the Pre-Raphaelite Beauty’. For Rossetti she was always the quintessential object of devotion, the woman who represented his soul, the animus to his anima, a mirror of himself, a Beatrice for his Dante.

Ophelia by John Everett Millais. Click on image to enlarge it.

Absorbed in their relationship, their love only turned sour when they married; supposedly suffering from consumption or from some other, unidentified illness, and always of ‘a nervous disposition’, the fragile Mrs Rossetti became addicted to laudanum. Following a still-birth she suffered post-natal depression and (apparently) took her own life with an overdose. The final part of the story is grotesque, a Gothic horror. In an act of melodramatic excess, Rossetti symbolized the death of his muse by placing his manuscript poems in her coffin; several years later when he decided he wanted to publish them, he exhumed her body and retrieved the papers – though not personally. Commentators noted with relish how the notebook was wormy, had to be disinfected, but still stank of the grave. It was the ultimate story of exploitation, and one which for which Siddall has acquired the status of a feminist martyr, a working-class woman condemned to be the object of male desire, a face without a personality, a objectified commodity to be abused. These are the argument lines of biographies by Jan Marsh (1989) and Lucinda Hawksley (2004).

Beauty, object, corpse: Siddall seems to exist on the periphery of her own life, and when we do see her, in contemporary memoirs such as William Allingham’s diary, the writers only give us the smallest of glimpses. She rarely spoke, rarely expressed an opinion, and what she did say was reported, usually in patronising terms, by others. But there was more to Siddall, or ‘Siddal’ as she became on Rossetti’s advice, than the mythologized narrative suggests. Like her husband, she was a poet and artist. Serena Trowbridge has published an edition of her verse and others have tried to rehabilitate her work as worthy of investigation in its own right.

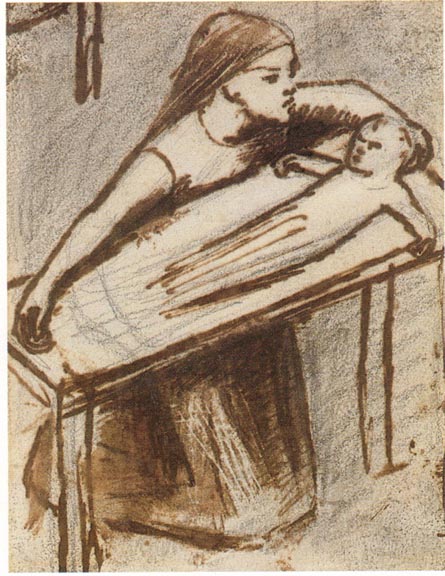

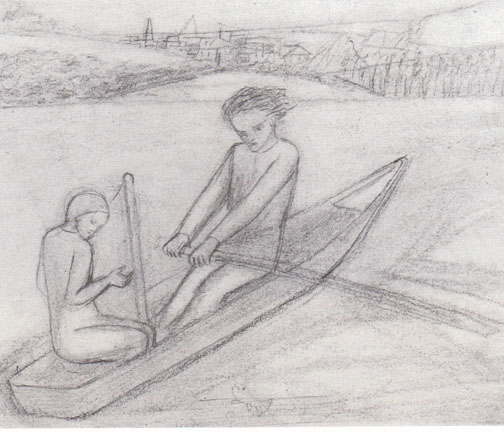

‘Beyond Ophelia – a Celebration of Lizzie Siddal, Artist and Poet’, Wightwick Manor, Wolverhampton (1 March – 24 December 2018), is a small exhibition which sets out to contribute to this process of rediscovery. Transcripts of her poems are shown but the main emphasis is on the art-work, most of which is taken from Wighwick’s own collection and formerly in the possession of Lady Mander, the art-historian who wrote a biography of Rossetti. The exhibition presents a handful of small-scale drawings in the form of rough sketches and studies, a couple of paintings in gouache, and finished designs in pen and ink. Her subjects, predictably, are Pre-Raphaelite themes: Lovers Listening to Music (1854) shows an embracing couple – recognizably figures of Rossetti and The Sid – attended by angels; and others include two versions of The Nativity, a drawing of the Madonna and Child, and the gloomy gouache, Haunted Wood.

The main focus, however, is on preparatory work for book illustration. Sister Helen depicts a scene from one of her husband’s poems, but most interesting is a small group intended for the Alfred Tennyson’s Poems, known as the ‘Moxon Tennyson’ (1857). This famous book contains designs by Rossetti, Holman Hunt and Millais, and at one point it looked as if Siddall might have become a contributor; Rossetti wanted her to work on the tome, and so did Emily Tennyson, the poet’s wife. The exhibition presents her illustrations for ‘The Palace of Art’ (Saint Cecilia), Sir Galahad, and The Eve of St Agnes. Praised by John Ruskin, who offered to purchase all that she produced, she must have felt that her illustrations would appear. None, however, was published; the first two subjects were designed by Rossetti and the last by Millais.

Four of Siddal’s works illustrated on our site: Left: Study for a Nativity. Middle left: The Rowing Boat Middle: The Lady of Shalott. Right: Clerk Saunders. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

None of the drawings proceeds to a final stage of engraving on wood and the reason for their non-appearance brings us – whatever Ruskin’s judgement – to a bald truth: Siddall’s designs are generally crude, and can only be viewed as the work of an amateur. Completely untrained, she can barely be expected to have done any better, and, whatever the claims that might have been made for her status as an artist in her own right, her skills are extremely limited. She only has a rudimentary grasp of modelling, space, proportion and the drawing of facial expressions, and her figures are contorted. Pre-Raphaelitism drew inspiration from the so-called Italian ‘Primitives’ of the Quattrocento, but Siddall is the genuine article: a primitive who is best described as a folk-artist.

This is not to say that her work is without interest. It is not impossible, for example, that her drawings for the Moxon Tennyson had some impact on her husband’s treatments. The swooning St Cecilia, her head drawn back in gawky rapture as the angel looks at her, may well have influenced Rossetti’s interpretation of the verse in which the angel not only looks at the saint but bites her forehead. The Haunted Wood, though practically illegible, could also have been an influence on Rossetti’s How They Met Themselves, in which two lovers meet their dopplegangers. Lizzie’s rough designs echo in the lines of her husband’s art, and in this respect, at least, she can be viewed as contributor to the development of Pre-Raphaelite imagery. Her work is otherwise deeply imbued with the visual tropes derived from her husband’s medievalist watercolours of the 1850s. The angular figures, claustrophobic space, emblematic detail and dreamy atmosphere are all borrowings from Rossetti’s gem-like paintings of the period. If he took ideas from her, the borrowing was asymmetrical, with most of her designs originating in her husband’s art.

So does Lizzie Siddall go ‘Beyond Ophelia’? Was she more than a model and muse? The exhibition suggests that she was, transforming her into an important creator and an artist of note. In my view this is an inflated estimation, a misreading that privileges the legend and not the facts. But she does occupy a small but interesting place in the history of Pre-Raphaelite illustration, offering alternative ways of visualizing Tennyson and nudging her husband in the direction of his final compositions. Her art as it stands is too weak to make any greater claim and can only be viewed as a small chip off the main block of Pre-Raphaelitism. Feminist critics would say that this judgement is unsympathetic, stealing her reputation just as Rossetti stole from Lizzie’s grave. Siddall is indeed a tragic figure, a practitioner dominated by greater talents as she struggled to find an artistic identity, borne down by suffering. Had she lived longer it is not impossible that she would have found her own way forward. Nonetheless, given the number of really talented, proficient Victorian women artist and designers — painters as different as Helen Allingham, Anna Blunden, Barbara Bodichon, Eleanor Fortescue Brickdale, Evelyn de Morgan, Rebecca Solomon, and Elizabeth Thompson (Lady Butler) come to mind — it seems rather unfair to British women artists to make Siddal(l) the center of attention.

Works Cited

Hawksley, Lucinda. Lizzie Siddal: The Tragedy of a Pre-Raphaelite Supermodel. London: Deutsch, 2004.

Marsh, Jan. The Legend of Lizzie Siddal. London: Quartet, 1989.

Trowbridge, Serena, Ed. My Ladys Soul: The Poems of Elizabeth Eleanor Siddall. London: Victorian Secrets, 2018.

Created 18 September 2018

Last modified 28 November 2018