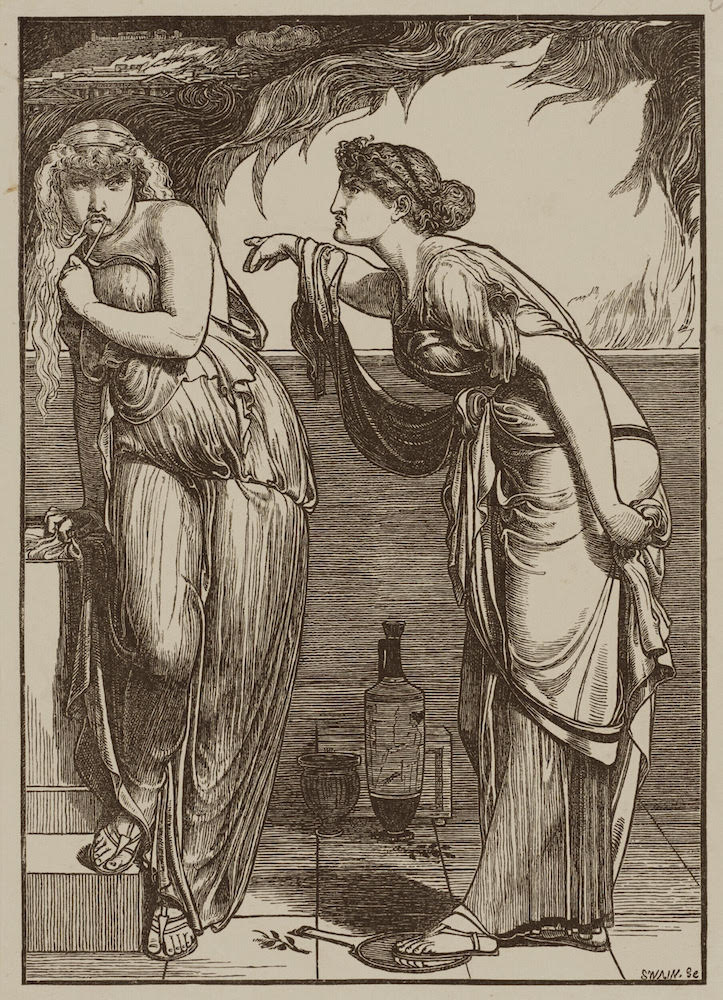

Helen of Troy (Helena) by Frederick Sandys (1829-1904). c.1867. Oil on panel. 15 ½ x 12 inches (64.3 x 56.2 cm). Collection of the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, accession no. WAG2633. Image courtesy of Walker Art Gallery under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial licence (CC BY-NC). Right: Helen and Cassandra. 1866. Wood engraving after F. Sandys by Joseph Swain. 6 7/8 x 4 7/8 inches (17.4 x 12.4 cm) – image size. Collection of the author. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Helen of Troy, or Helena as it was initially titled, was not exhibited in London at the time it was painted but was later shown at the Art Treasures Exhibition in Manchester in 1878, no. 239. Betty Elzea has described the painting: "Bust of a young woman with head and shoulders facing the spectator, but the eyes, beneath frowning brows, look upwards to the right. The top of the head is seen as if it were tilted forward, but the necessary foreshortening is not conveyed satisfactory. Helen's body appears to be nude, and she wears two necklaces in classical revival style (fashionable at the time). Her long wavy, coiling, minutely observed and depicted hair is an important feature of the picture. A rose is tucked into it, above her right shoulder. In the background is a vine-like plant with blue flowers" (191). Mary Bennett has described these flowers as "blue bell-flower sprays of bougainvillea type" (184). Helen is again modelled from Mary Emma Jones.

The depiction of Helen is derived from Sandys's earlier illustration of Helen and Cassandra published in Once a Week, Volume I, on 28 April 1866, facing page 454 to accompany a poem written by Alfred B. Richards. Both images portray Helen with her same sinister sideways glance. Helen's image in the painting differs from the illustration in the hair being arranged differently, she is not biting on a lock of her hair, and she is wearing a rose in her hair. Helen is not pouting like a petulant child as much either as compared to the illustration. Helen wears her expensive necklaces only in the painting. The background of flowers differs from the flames with Troy on fire in the distance as seen in the print.

Virginie Thomas has shown how Sandys has portrayed Helen as one of his characteristic femme fatales:

The image is clearly characterised by her disdainful pout and her dark gaze – in spite of her blue eyes – underlined by her frowning in the tradition of the faces painted by Caravaggio but also typical of Sandys's Femmes Fatales. Helen's reddish hair creates whirlpools from the movements of her curls. The choice of red hair was almost certainly deliberate because, according to Michel Pastoureau, it is the colour of demons, of hypocrisy, of lying and of betrayal. Helen may be considered as Aphrodite's victim but she is also guilty of betraying Menelaus – leaving him for Paris – and, in so doing, occasioning the Trojan War. Helen's deadly identity finds an echo in the red colour of her lips, of her coral necklace whose beads evoke blood drops, and of the rose that she wears in her hair. In Antiquity roses had a deadly connotation, since the Feast of Roses was part of the ceremonies linked to the celebration of the dead. Helen displays a carnal beauty, as we can judge from the presence of her naked plump body in the foreground; but nonetheless a nefarious beauty. However, the viewer is once again protected from her bewitching power and from possible objectification by the diversion of her threatening gaze; while Helen herself becomes an object of representation and contemplation. Nevertheless, even though the viewer manages to escape Helen's gaze, he is not spared the "gaze of the painting. [282]

Thomas may be incorrect, however, that Sandys deliberately used Helen's red hair for symbolic purposes since Mary Emma Jones's natural hair colour was red.

Contemporary Views of Sandys's Painting

When the painting came up for sale at Ernest Gambart's sale at Christie's in March 1871 it was noticed by William Michael Rossetti who wrote disparagingly of it in his diary dated 29 March 1871: "Sandys's Helena which was cited in connection with the dissention between him and Gabriel is not, I see, founded upon Gabriel's treatment of the same subject: it is a very bad picture, about the worst thing Sandys ever produced" (Bornand 52).

In a letter of 5 May 1907 from the artist Anna Lea Merritt to the prominent American collector Samuel Bancroft, Merritt mentions having seen Sandys's picture and discusses both its virtues and inadequacies: "One of my friends has a beautiful Helen of Troy by Sandys. Nothing could be more beautiful than her hair and the brilliancy of flesh tints. The surface is exquisite and the expression cruelly heartless which Helen must have been. Alas somehow it is spoiled by want of structure, you can't guess where her bones are!" (qtd. in Elzea, 191).

Victorian Paintings of Helen of Troy

Helen of Troy was a favourite subject of Victorian artists. Full-length versions of the classical heroine exist. The one by Frederic Leighton, Helen on the Walls of Troy, of 1865 is in a private collection. Evelyn De Morgan's Helen of Troy of 1898 is in the collection of the De Morgan Foundation. A half-length frontal portrait of Helen of Troy by Edward Poynter of 1881 is in the Art Gallery of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia. Dante Gabriel Rossetti's bust-length version of Helen of Troy of 1863 is in the Kunsthalle Hamburg. Sandys's version of Helen of Troy was one of three subjects that led to a falling out between him and Rossetti, and a temporary termination of their friendship. In a letter of 1 June 1869, Rossetti had accused Sandys of plagiarizing his ideas, at least in general approach if not in specific details.

Bibliography

Anderson, Gail-Nina, and Joanne Wright. Heaven on Earth. The Religion of Beauty in Late Victorian Art. London: Lund Humphries/Djanogly Art Gallery, Nottingham, 1994, cat. 57, 108.

Bennett, Mary. Artists of the Pre-Raphaelite Circle. The First Generation. London: Lund Humphries, 1988, cat.2633, 184-85.

Bornand, Odette. The Diary of W. M. Rossetti 1870-1873. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1977.

Elzea, Betty. Frederick Sandys 1829-1904. A Catalogue Raisonné. Woodbridge, Suffolk: The Antique Collectors' Club Ltd., 2001, cat. 2.A.103, 191.

Helen of Troy. Art UK. Web. 16 July 2025.

Helen of Troy. National Museums Liverpool. Web. 16 July 2025.

Newall, Christopher. The Pre-Raphaelites. Stockholm: Nationalmuseum, 2009, cat. 147, 215.

Thomas, Virginie. "The Female Body in Frederick Sandys's Paintings, or the Sublimation of Desire." Sensational Visual Pleasures in Cinema, Literature and Visual Culture. The Phallic Eye. Eds. G. Padva and N. Buchweitz. London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2014. 277-288. HAL Open Science. Web. 16 July 2025. https://hal.science/hal-04180530v1/document

Wildman, Stephen. Visions of Love and Life. Pre-Raphaelite Art from the Birmingham Collection, England. Alexandria, Virginia: Art Services International, 1995, cat.85, 256-57.

Created 16 July 2025