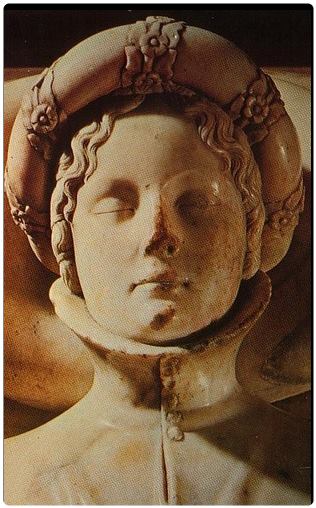

Tomb of Ilaria del Caretto, Lucca Cathedral by John Ruskin. c.1874. Pencil, watercolor and bodycolour. Collection: Ruskin Foundation, Ruskin Library, Lancaster University. ©Ruskin Foundation. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Photographs of the figure of Ilaria from Wikimedia Commons, by (r) Alessandro Vecchi, and (l) Xenxax, on the Creative Commons Licence.

Throughout his writings Ruskin expressed delight in such impressions of peace and repose. John D. Rosenberg has therefore suggested that

in art as in life he was most moved by the kind of beauty which possesses the unchanging . . . remoteness of death. . . Peace, youth, and death were always associated with Ruskin's moments of profoundest feeling: with the 'marble-like' beauty of the girl at Turin, who lay motionless on the sand, 'Like a dead Niobid'; with the girls at Winnington, immobile and innocent, as they listened to music; with the perfect repose of Della Quercia's figure of the sleeping Ilaria di Caretto, which he loved above all other statues. [The Darkening Glass, 205]

Ruskin's praise of della Quercia's sepulchral monument for Ilaria di Caretto, his careful attention to tomb sculpture in The Stones of Venice, and his strong approval of Wallis's Death of Chatterton and Millais's Ophelia all argue for Rosenberg's view. At the same time, Ruskin's love of the intense and infinitely various hues of nature (and of her prophet Turner) does not permit one to accept the idea that such beauty most moved him: one remembers that his vision of the Alps, like Turner's art, mixed tumult and calm, change and permanence, conflict and peace.

Related Material

- Cathedral of San Martino, Lucca, c.1874

- Pillar in the Porch of San Martino, Lucca, c.1874

- Detail of façade, San Martino, Lucca, 1874

- 1846 daguerrotype of Façade of Lucca Cathedral

- 1846 daguerrotype of the Tomb of Ilaria del Caretto

- 1846 daguerrotype of the Tomb of Ilaria del Caretto (version in Works, 4.122.

- Ruskin Relics (essay by Caroline Murray)

Bibliography

Wildman, Stephen. John Ruskin: Photographer & Draughtsman. Compton, Surrey: Watts Gallery, 2014. p. 29

Ruskin, John. Works, "The Library Edition." eds. E. T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn. 39 vols. London: George Allen, 1903-1912.

Last modified 4 March 2014