This essay first appeared as the author's journal entry for 24 June 2020 on Wordpress. Many thanks to Caroline Murray for letting us reprint it here. The illustrations all come from the original entry, except for two, which we already had on our own website. Click on the images to enlarge them, and usually to find out more about them. Unless otherwise indicated in the caption, you may use them without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer or source and (2) link your document to the original essay, or to this URL, or cite it in a print one. — Jacqueline Banerjee

Left to right: (a) The attractively bound edition of Ruskin Relics. (b) The inscription by Miss Hutchinson. (c) The bookplate for Alexandra Hall in English and Welsh ("Neuwadd" meaning Hall in Welsh). [Click on all the images to enlarge them and usually for more information about them.]

came across a reference to this 1903 book last week, and was fortunate enough to find a copy (on Abebooks), which arrived a few days ago. It was presented by "Miss Hutchinson" to Alexandra Hall in 1905. Alexandra Hall (of which the bookplate is in English and Welsh) was the first hall of residence for female students at the University College of Aberystwyth, and was founded in 1896; by 1911, it housed 168 students. Many pages of the book, and all the plates, are stamped as a sign of possession: what worries me slightly is that there is no de-accession mark. Leaving the issue of possible malfeasance on one side, the book is well produced (by Isbister and Co., 15 & 16 Tavistock Street, Covent Garden), with attractive gold blocking on the front, and Isbister’s colophon blind-blocked on the back board.

came across a reference to this 1903 book last week, and was fortunate enough to find a copy (on Abebooks), which arrived a few days ago. It was presented by "Miss Hutchinson" to Alexandra Hall in 1905. Alexandra Hall (of which the bookplate is in English and Welsh) was the first hall of residence for female students at the University College of Aberystwyth, and was founded in 1896; by 1911, it housed 168 students. Many pages of the book, and all the plates, are stamped as a sign of possession: what worries me slightly is that there is no de-accession mark. Leaving the issue of possible malfeasance on one side, the book is well produced (by Isbister and Co., 15 & 16 Tavistock Street, Covent Garden), with attractive gold blocking on the front, and Isbister’s colophon blind-blocked on the back board.

The author, W.G. Collingwood (attributed), Self Portrait (Sea Captain). Credit: The Abbot Hall Art Gallery, Kendal, Cumbria.

It was written by William Gershom Collingwood (1854–1932), the son of two watercolour artists, who as a boy travelled with his father in the Alps. He also spent holidays on the shores of Lake Windermere, so hindsight would tell us that it is hardly surprising that when he went up to University College, Oxford (where he obtained a first in Greats) in 1872, he met, and had his life transformed by, John Ruskin.

For the next thirty years, most of his life was dedicated to the Master, so much so that he moved first to Gillhead on Windermere and then to Lanehead on Coniston, to be close to him. (By an odd quirk of literary history, his friend Arthur Ransome visited him there, and went out sailing with Collingwoood’s children on a boat called the Swallow ... all four children had very interesting afterlives; the son, Robin, grew up to become R.G. Collingwood, philosopher and historian of Roman Britain.)

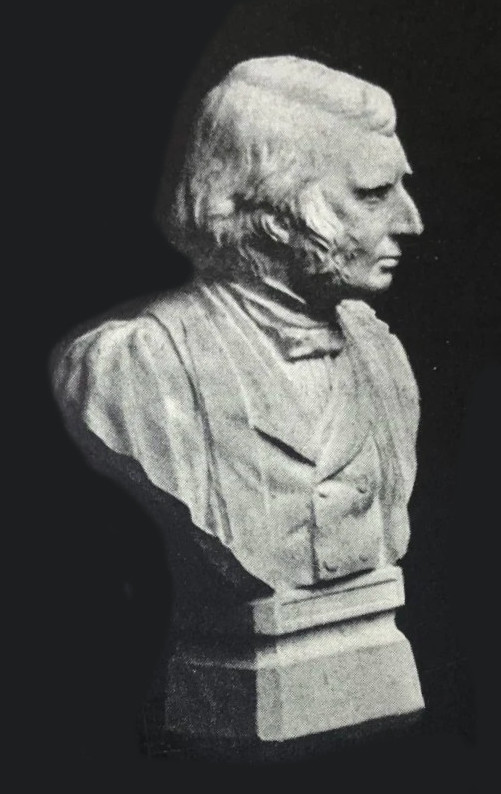

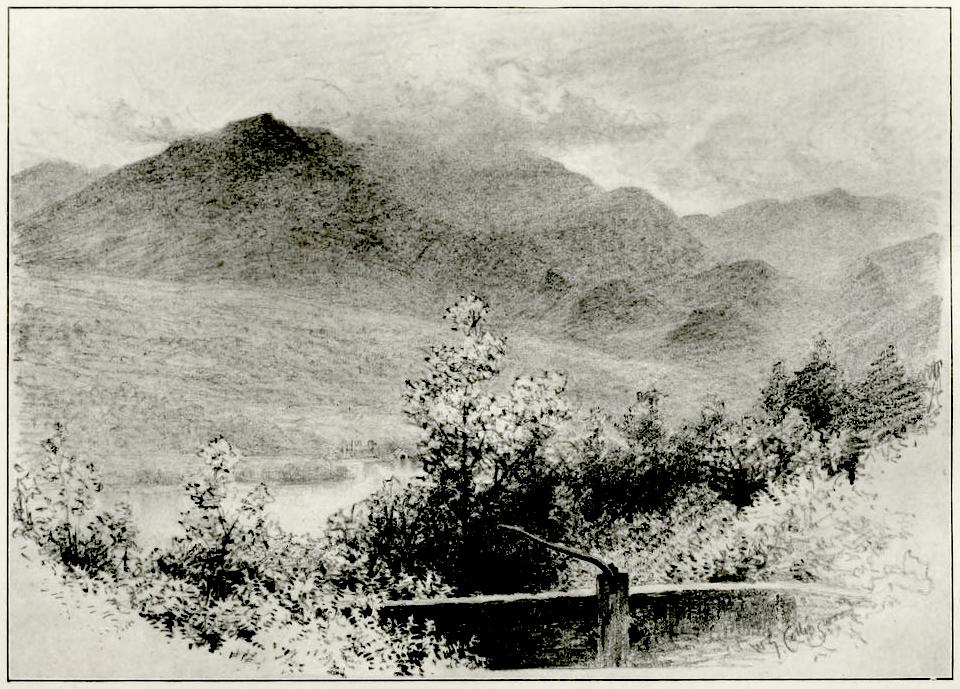

Left: Photograph of Benjamin Creswick's bust of Ruskin in the 1870s, taken by Miss Hargreaves, from Collingwood's book. Right: Brantwood, John Ruskin’s home overlooking Coniston Water, where he lived from 1872 until his death. © VisitCumbria, reproduced with permission.

W.G. Collingwood acted as secretary, editor, translator, travelling companion and draughtsman – to say nothing of road-builder at Hinksey and harbour-constructor at Coniston. Ruskin encouraged him to study at the Slade School of Art after he graduated from Oxford, and among the ‘Relics’ in the book are some very funny descriptions of a group of students trying to copy Turner water-colours or medieval illuminated manuscripts under Ruskin’s supervision.

Collingwood wrote a biography of the Master in 1893, and re-wrote it in 1900 after Ruskin’s death, but it was rather superseded by E.T. Cook’s two-volume work of 1911. Having read in the ODNB "that Collingwood declined to edit the Ruskin Library Edition because he saw it as a mere money-making venture by Ruskin’s executors," I wonder how much love was lost between him and that rival keeper of the flame, Edward Tyas Cook, eventual editor (with Alexander Wedderburn) of the Works of John Ruskin in 39 monumental volumes (1903–12).

[Contents] page of Ruskin Relics.

Ruskin Relics is in fact a cut-and-paste job, consisting of fourteen chapters, twelve of which are disarmingly described as "reprinted, with some editions, from Good Words, the long-running monthly periodical published in Edinburgh, of which the purpose was to provide matter which "the devout should be able to read on Sundays without sin"; a chapter on Ruskin’s drawings, from the prefatory notes to Collingwood’s catalogue of a Ruskin exhibition in 1901; and the first chapter, "Ruskin’s Chair" (shades of Charles Dickens’s well known "Empty Chair"?), "newly written for this book." Most of the illustrations are by Collingwood himself, though a few are reproductions of Ruskin’s own works, and there are some photographs.

Left: Photo of the study at Brantwood, taken by Miss Brickhill, showing some of Ruskin’s chairs. Right: Part of the garden at Brantwood, by W.G. Collingwood. (Brantwood these days grows a lot of highly colourful azaleas and rhododendrons – would the Master have approved?)

I enjoyed "Ruskin’s Gardening," which (unsurprisingly) describes him as an artist of landscape, tweaking Nature here and there for aesthetic effect, rather than a bedder-out of pelargoniums (which, I think he wrote somewhere, are simply too red).

"Ruskin’s Old Road" describes a journey they took together in 1882 through France to Switzerland, and down into Italy (following the route familiar to Ruskin since his travels in the 1840s), with the Master "very much broken down in health, despairing of himself and his mission." At Calais, he began to cheer up, especially when the old chef at the hotel "who was still in the flesh, and remembered former visits ... sent up a capital dinner." (It’s remarkable how many times Ruskin, having been shown to his room, immediately goes down to the kitchen for negotiations.)

W.G. Collingwood, An Old house at Laon (1882). © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford.

So they went on to Laon, Reims (where he described the cathedral as "confectioner’s Gothic" and despised the champagne), Troyes, Sens and Avallon – at each place the mornings were spent drawing, the afternoons walking in the countryside, always with an eye to geology. From Dijon, Ruskin made an excursion to Cîteaux, where he was horrified to discover that the monks had been replaced by "an industrial school of the ugliest," but he was then cheered by a visit to the birthplace of St Bernard at Fontaine-lès-Dijon, before starting to ascend into the Jura mountains.

Ruskin’s former house at Mornex (photo from vol. 17 of the Works of John Ruskin).

The chapter ends at Mornex (south-east of Geneva, but back in France, due to the vagaries of the border), where Ruskin found that the house where he had lived in the 1860s was now a restaurant: "He was, though he did he did not say so, rather cast down by the change ...; but brightened when the landlord guessed who he might be, and quite cheered up – with that last infirmity of noble minds – on hearing that the English sometimes came to see Ruskin’s house."

He wrote a letter home from Mornex, and apologised to the recipient for beginning it on the wrong side of the paper (presumably the "front" was embellished with the hotel’s address), because "he had taken a glass too much Burgundy." When this letter was later published it seems to have "pained and alarmed" some of his friends – the great aesthetician not only a gourmet but a wine-bibber too?

My favourite chapter is "Ruskin’s Ilaria" – not least because I am still cast down at not having gone to Lucca as planned on 18 March. Continuing the 1882 journey, on 22 September they arrived in Turin ("Filthy city""), and later Genoa fared little better – "a day of disgust at all things." They caught the train to Pisa (Ruskin, in spite of his abominating the railways in principle, wasn’t above using them in practice), but even that failed to charm – the noise of the railway, "diabolical" trams and too many smoking chimneys since his last visit. So "at noon, he ordered the carriage for Lucca."

Henry Roderick Newman (one of Ruskin’s artist assistants) painted this watercolour of the façade of the Duomo di San Martino, Lucca, in 1885. Collection of the Guild of St George, Museums Sheffield.

Signor Ruskino was expected at the Hotel Royal of the Universe, and having greeted the owner and staff, and had a consultation with the cook, he went to see Ilaria del Carretto.

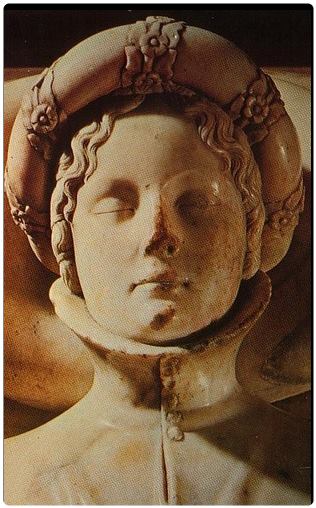

She lies now as she did then, with her little dog (a symbol of fidelity) at her feet, in a side-chapel of the Duomo di San Martino, dead in childbed at the age of twenty-six in 1405. The sculptor, Jacopo della Quercia (c. 1374–1438), was commissioned to make the memorial by her husband, Paolo Guinigi (c. 1372–1432), a member of the ruling family of Lucca who had risen to the top (as so often in Italy) through internecine murders plus the plague. He was not exactly a good egg, but he did improve the commercial status of his city, not least by the trade of Carrara marble and by encouraging silk-weaving. But in the wider world, it is the funerary monument of his wife for which he is remembered.

Watercolour by John Ruskin of the tomb of Ilaria del Carretto (c. 1874). Collection: © Ruskin Foundation,Lancaster University.

According to Collingwood, Ruskin fell in love with Ilaria in 1845, while "for the first time wandering free and working out his own thoughts among the Old Masters … he “went up the Three Steps and in at the Door” of the chapel. As he himself wrote, "It is forty years since I first saw it, and I have never found its like."

Left: The head of the statue. Right: Ilaria and her dog. (Wikimedia Commons)

I did not know, until I read the book, that the memorial (recent study has revealed that Ilaria was not in fact buried there, but in the church of Santa Lucia, along with other members of the Guinigi family) was broken down by Paolo’s enemies after he had been driven from Lucca, but the effigy survived, apart from slight damage to the nose, and the monument was later restored.

Jacopo della Quercia cannot have known what Ilaria looked like (he was summoned to Lucca a year after her death), and perhaps likeness is not the point. As Ruskin says of the features of her face, "there is that about them which forbids breath; something which is not sleep and not death, but the pure image of both." I very much look forward to going up the three steps and in at the door to visit her again.

Bibliography

"Brantwood – Home of John Ruskin." VisitCumbria. Web. 3 July 2020.

Collingwood, W. G. Ruskin Relics. London: Isbister and Co., 1903.

Hewison, Robert. "Ruskin, John (1819–1900), art critic and social critic." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Online ed. 3 July 2020.

Ruskin, John. The Works of John Ruskin. Eds. E. T. Cook and A. Wedderburn. 39 vols. London: George Allen, 1903-12.

Last modified 5 July 2020