Unless otherwise noted, illustrations come from the exhibition press pack or online image sheet kindly provided by Tate Britain. Special thanks to Daniel Crouch Rare Books for sending in a large image of Walter Crane's Imperial Federation map, and to Leeds Museums and Galleries (Leeds Art Gallery) for their image of Edward Armitage's Retribution. [Click on the images to enlarge them, and sometimes for more information about them.]

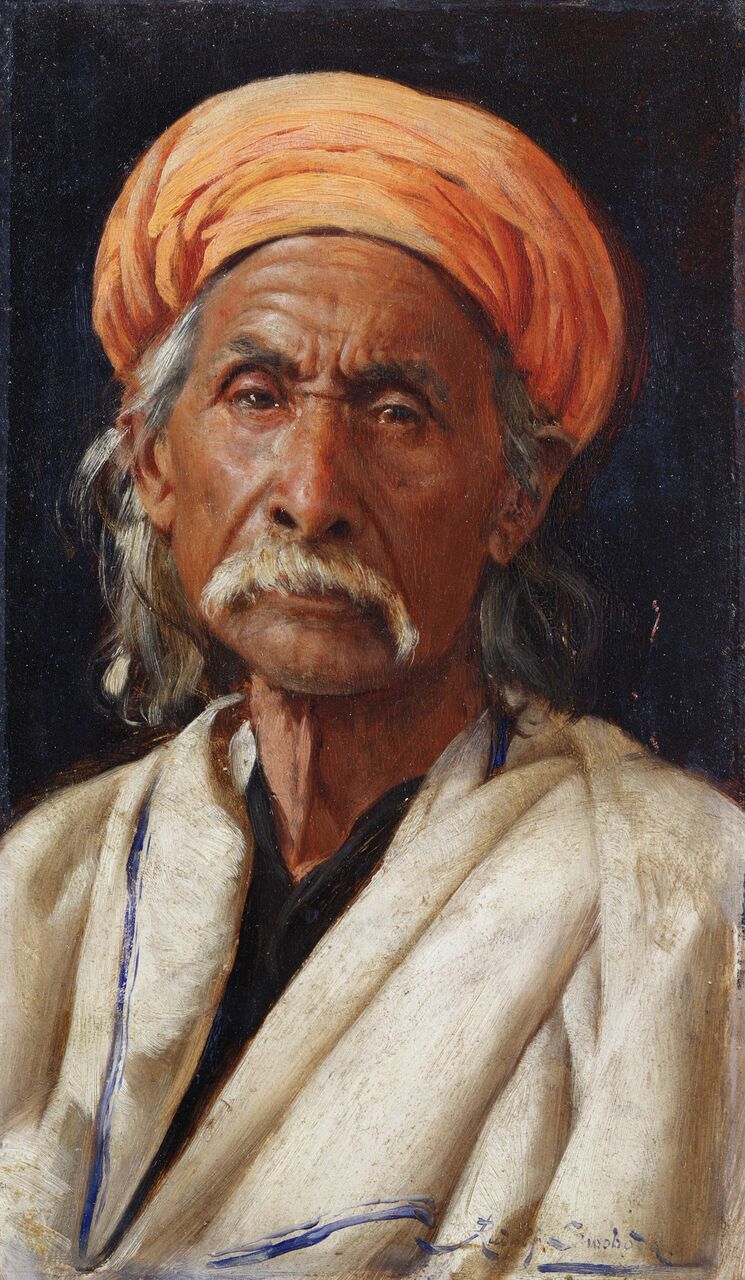

Left: Rudolf Swoboda's Bakshiram, 1886, oil paint on panel, 260 x 159 mm. © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, 2015. Right: Cover of the book accompanying the exhibition — Artist and Empire: Facing Britain's Imperial Past, edited by Alison Smith, David Blayney Brown and Carol Jacobi.

Rudolf Swoboda's Bakshiram (1886) is hardly the most spectacular work on display at Tate Britain's current exhibition (25 November 2015-10 April 2016). In fact it is rather lost in the "Trophies of Empire" room, where it has to jostle for attention with striking canvases like George Stubbs's A Cheetah and a Stag with Two Indian Attendants (c.1764) and Benjamin West's full-length portrait of Sir Joseph Banks (1771), which shows the naturalist amid (and wearing) items brought back from his South Sea expeditions. But the small oil-on-panel close-up of Bakshiram, an elderly Indian in common garb, was a brilliant choice for advertising the exhibition, and for fronting the little visitor's guide.

Bakshiram was, and was not, a trophy of Empire. He was a potter, reputed to be over 102 years old, and so skilful that the Queen bought one of his vases. As David Blayney Brown explains in the book, he was one of a group brought over from the Central Jail in Agra, where they had been taught their skills, to demonstrate Indian crafts at the Colonial and Indian Exhibition of 1886 (43). So his portrait does belong with other depictions of "trophies." But the Viennese artist Swoboda (1859-1914), who painted him and several of the others for the Queen while they were here, has caught an innate dignity, a stillness, in him. His portrait speaks not of acquisition or subjection, but of an ancient culture fundamentally untouched by the vicissitudes of time, over which the British had ultimately no hold. The hauntingly direct gaze turns our own eyes inward, raising discomfiting questions about the whole imperial enterprise. In short, Swoboda, while participating in a thoroughly imperialistic project, has managed to rise above it, and make the object of our curiosity a vehicle of interrogation.

"Mapping and Marking"

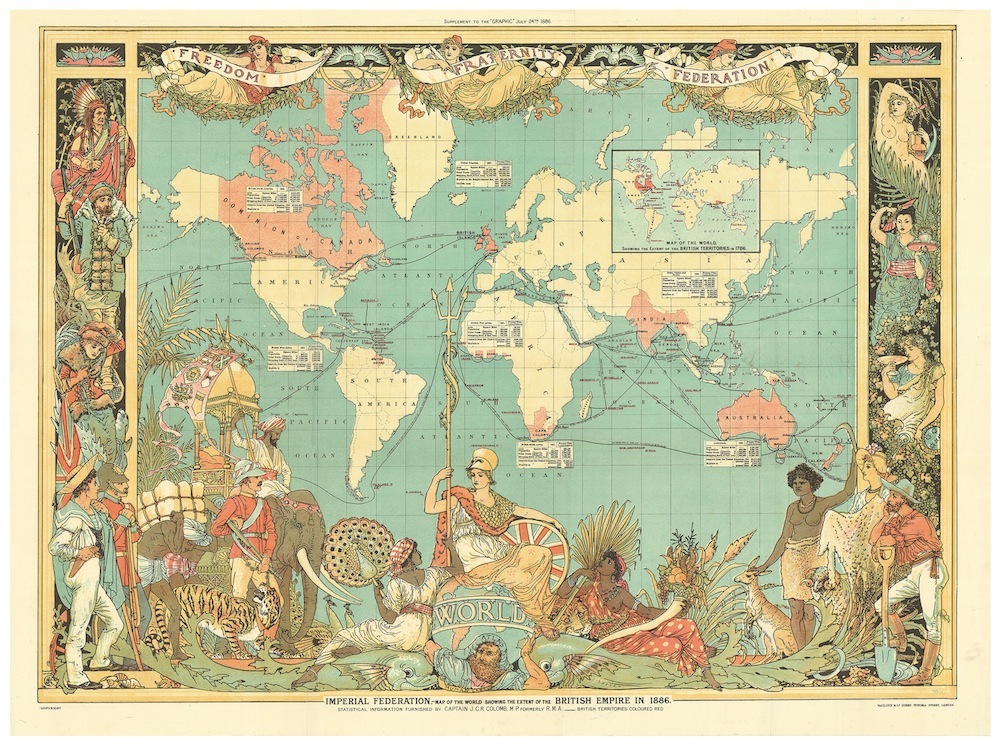

Walter Crane's Imperial Federation: Map Showing the Extent of the British Empire in 1886, published by Maclure & Co. as a Supplement to The Graphic, 24 July 1886. Credit: Daniel Crouch Rare Books.

That, of course, is the whole point of Smith's present project as lead curator of the exhibition; and the extent to which this is facilitated by the artists themselves is of huge interest. The probing starts in the first room, on the theme of "Mapping and Marking," which surprises the visitor with some unusual exhibits for an art gallery. The flags hanging overhead bear Union Jacks, but are far from jingoist. These artefacts, cotton appliqué works by the Fantes on the old Gold Coast, in a style still employed in Ghana today, were made for military companies supporting the British. But they expressed so much that was distinctively native that they were considered nationalistic, and banned. The maps displayed in this room are just as problematic in a different way. Cartography was vital for development — for defence purposes, too — but instead of just representing what was there, these maps often served as a statement of ownership, giving new names to territories and their features, and revealing ambitions as well as asserting claims. However, here there was scope for more subtle intervention on the British part. As a socialist himself, converted to the cause by William Morris, the artist and designer Walter Crane designed the map showing the "Imperial Federation" with figures in the border suggestive of exploitation. In the lower left-hand corner, for example, sandwiched between smartly uniformed representatives of the Empire, a poor man in a loincloth is bent double under a heavy bale.

Close-up of the left-hand corner of Crane's map.

Discussing this map, Alison Smith sees Crane as asserting "the role of socialism within an imperial framework" (34); but does that go far enough? Crane could also be seen as questioning empire itself. Recalling his own visit to India in 1906, Crane wrote:

it is not a comfortable thought for an Englishman, loving freedom, and accustomed to the principles of popular and representative government at home, to realise that this vast empire is held under the strictest autocratic system; and that the national aspirations that are now beginning to make themselves heard and felt should be entirely ignored, and the voice of native feeling sternly suppressed. [ix]

Interestingly, the map was published to mark the Indian and Colonial Exhibition mentioned above (34). Crane, like Swoboda, was having his own say on it.

However, probably the best known and certainly the most arresting artwork in this room is John Everett Millais's The North-West Passage: "It might be done, and England should do it" (1874), in which a young woman reads to (it would seem) her elderly weather-beaten father from his log book, with a map lying spread on the table beside him. Supported by this feminine element, the man is the very epitome of heroic determination to open up the world to Britain at any cost. Such juxtapositions make this a vital, thought-provoking and thoroughly absorbing exhibition.

"Trophies of Empire"

Marianne North's Entrance to the Cave of Karlee (Karli), Maharashtra, 1878. Credit: The Board of Trustees of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

Large, stirring canvases by famous artists are always the crowd-grabbers, and the Stubbs and West paintings mentioned above perform that function in the second room, which is dedicated to collecting. In the Artist and Empire book, Brown mentions the debate about whether collecting was a "by-product of Empire" or "contributed to its making" (41). Probably it was both. At any rate, the result was the same, the swelling of domestic "cabinets of curiosities" into collections that needed houses and then dedicated museums to house them. The Horniman Museum comes to mind, though, in the book, it is only mentioned in connection with some Sierra Leonean exhibits at the very end of the section. Unfortunately, many of the smaller works here, including Swoboda's, do tend to be overshadowed by the large ones. Archival items do not come off very well in these contexts, especially single items. For example, there is just one painting by Marianne North, from the Herbarium, Art and Archives collections at Kew. It is of the entrance to the Cave of Karlee in Maharashtra, preferred to an earlier engraving by the prolific architectural historian of India, James Fergusson, for its greater animation (specifically, the figure of the man on the left, performing a ritual with red paint). It is a pity not to see Fergusson himself represented here, but good, on the other hand, to have a woman artist represented for a change, and also to have a spot of life in the rather dauntingly alien scene.

Similarly, it was disappointing to see (East India) Company painting sparsely represented; but at least this important instance of "cross-cultural assimilation" (65) does not pass unnoticed, and there are a couple of closely detailed architectural drawings by unnamed Indian artists, one in European perspective. Again, it is a matter of balance. Choosing pieces for this section must have been extraordinarily difficult: the range is from a pre-Victorian Maori gable ornament to a Victorian-era Haida tobacco pipe sporting a carving of a paddle-steamer. Photographs are also included, alongside other work in a variety of media, such as watercolour, ink and wash, sepia wash, and gouache. Getting the most out of such different exhibits requires more attention to wall labels than usual — and makes the book an absolute must for a full understanding.

"Imperial Heroics" and "Power Dressing"

Edward Armitage's Retribution, 1858. Credit: Leeds Museums and Galleries (Leeds Art Gallery).

Inevitably, the two rooms on the themes of "Imperial Heroics" and "Power Dressing" display the most dramatically pro-empire works, those hardest to digest in the present age. This was how the empire saw itself — striding across the world, mighty in conquest, valiant in defence of conquest, heroic even in defeat, and led by inspirational figures who sometimes reflected back the exotic cultures in which they played such prominent roles. Here then are some of the great moments of imperial history: Sir William Young Conducting a Treaty with the Black Caribs on the Island of St Vincent, for instance, painted by his accompanying artist Agostino Brunias in about 1773. Brunias shows Young seated at ease in his pristine white uniform with scarlet jacket, extending a gracious hand to the almost naked Caribbeans, while the watchful dog beside him bares his teeth. Every picture here tells a story, and, again, the book provides helpful commentaries, drawing attention to details that are easily missed when going round a popular exhibition. The double-page spread of this painting in the book is particularly useful. Edward Armitage's Retribution of 1858 is another striking historical painting with a background that now needs elucidating. It shows the British revenge for the massacre of women and children at Kanpur during the Indian struggle for independence. There is no sly subversion on the part of the artist here. Rather, the dreadful (if reciprocal) atrocities of the enraged British are dressed up as righteous punishment, with the Bengal tiger standing in for the Indian victims, including those who had remained loyal to the British. How ironic it is, in view of such a painting, that everything was justified in the name of spreading a civilising influence! But here too is Thomas Jones Barker's The Secret of England's Greatness (c. 1863), the famous painting of a young and earnest Queen Victoria, watched gravely by her husband, handing a bible to an African prince. Not that such an episode actually occurred, as Smith explains; and even at the time, some demurred: apparently the painting was lampooned in Australia "for promoting religious rather than economic exploitation as the real source of Britain's power and wealth" (109). It is even more impossible to take the painting at face value now.

Though touchingly solemn in Barker's version of her, the Queen herself cannot be exonerated. Rather lost among the more fantastically costumed and often overbearing figures in the paintings of the "Power Dressing" room are two busts by Carlo Marochetti, of Princess Gouramma of Coorg and the Maharajah Duleep Singh. These two scions of noble Indian families (daughter of the deposed Raja of Corg, and the youngest son of Ranjit Singh, founder of the Sikh Empire, respectively) were both brought to England, where the Queen made much of them. But they gaze sadly away from us from their tinted marble. Did Marochetti, an exile himself, recognise the falseness of their positions? It is possible, because he was certainly a man of feeling. Instead of marrying each other, as the Queen had hoped, these two young people took their own ways, the Princess marrying a colonel thirty years her senior and dying of consumption at the age of twenty-three; and Duleep Singh, tired of playing at being an English aristocrat, turning back to Sikhism and eventually dying in France — still in exile — in 1893.

Elizabeth Butler (Lady Butler), The Remnants of an Army, 1879. Credit: Tate.

But Elizabeth Butler's The Remnants of an Army: Jellalabad, January 13th 1842 goes furthest here in demonstrating the human cost of empire. Inspired by a debacle of 1839, it shows the sole survivor of a huge caravan of soldiers — a caravan made up of Indian sepoys and attendants, as well as British and European soldiers – struggling towards the British fort. Wounded, clinging to the saddle of his beaten horse, Dr William Brydon, an assistant surgeon in the Bengal Army, is valiant only in endurance, and he is almost past that. Smith is very measured in her commentary on this painting, suggesting that Butler's evident sympathy does not represent an "unequivocally anti-imperialist" stance (110). But in showing what war does even to those who survive, this memorable work calls into question the whole idea of glorious conquest, in the service of any cause.

"Face to Face" and "Out of Empire"

After striking works in the previous room by masters like Van Dyck, Reynolds, John Singer Sargent and Augustus John, the last two rooms might be expected to seem anti-climactic. But they do not. As the themes "Face to Face" and "Out of Empire" suggest, they are more confrontational, though still not blatantly so. The Tate's own paintings by Johan Zoffany in Room 5 exemplify this admirably. In both, the artist appears to depict close Anglo-Indian relationships, but there are disturbing nuances, especially in Colonel Blair with his Family and an Indian Girl (1786). Domestic scenes hardly feature in the exhibition, and this one presents such a pleasant family group that it is easy to overlook discordant elements. One is the triptych on the wall featuring Indian rituals of widow-burning and self-mutilation. The Blairs have turned away from it themselves. What is more, their children's Indian companion can only be a lowly servant girl, not a playmate. Such things considered, the family's parti-coloured pets may well make an ironic comment on their owners' show of being happily at home in India. Zoffany, who spent six years there himself, has raised a quizzical eyebrow – as this artist was apt to do.

The theme of "Face to Face" allows for a host of such curious, jolting encounters. Amongst these are portraits of "some of the very first known individuals of the Eora Nation" of Sydney aboriginals (168), with their startling body-painting; Thomas Rowlandson's etching of super-voluptuous Rachel Pringle of Barbados; and Thomas Hickey's Three Princesses of Mysore, one of whom is unexpectedly and shyly showing where she has been vaccinated against smallpox. Included also are evocative wooden figures by Nigerian wood-carvers which turn the gaze back on the Victorians themselves. As well as endearing figures of members of our own royal family, here are the explorer Mary Kingsley, shown with a long thin pointed nose, piercing eyes and a very local take on her prim high collar; and a District Commissioner by the name of W. Ross-Brown, who sports a neat little moustache and a checked, peaked, off-duty cap. Whether they "went native" or not, how curious they must all have seemed, these westerners with their strange ways! And yet, to the dismay of the more confident or antagonistic, many not only accepted but aped them. In My Love of My Own Country is as Big as I am of about 1917, Gaganendranath Tagore (whose uncle, the more famous Rabindranath Tagore, and brother Abanindranath, are both represented in the final section) portrays an overweight Bengali incongruously flaunting his patriotic feelings along with his waistcoated paunch. The influence of Beardsley and other European graphic artists is clear for all to see.

Sonia Boyce's Lay Back, Keep Quiet and Think of What Made Britain so Great, 1986. Arts Council Collection. South Bank Centre, London © Sonia Boyce.

Even with hostility, such cross-fertilisations were bound to occur, and the last thematic category in both exhibition and book indicates ways in which contact with other cultures inspired subsequent art movements. With artists in or from the newly independent nations using a variety of avant-garde art forms to interrogate the imperial past, we are looking here at the emergence of what Carol Jacobi calls "trans-national modern art" (207). To take just two examples, Sonia Boyce's four-panelled Lay Back, Keep Quiet and Think What Made Britain so Great references different countries' colonial pasts and relationships with Britain, re-arranging and undercutting these references on a subtly changing wallpaper pattern. Similarly, Donald Locke's Trophies of Empire presents a new take on the cabinet of curiosities, with partitioned wooden shelves displaying resonant cylindrical forms, suggestive of everything from sugar-cane plantations and slave manacles to parlour knick-knacks — and, in the process, cross-referencing the implications of these disparate objects as well. These two works, by artists of West Indian parentage and British Guyanese background respectively, must stand in here for many others which call for close attention. Incidentally, the latter, with its use of wallpaper design, reminds us of something else that is not included here — the influence of Indian design in the late Victorian period, for instance on the textile magnate Thomas Wardle, who, like Crane, travelled to India and was deeply sympathetic to the workers in the silk industry there.

As always in a exhibition on such a scale, some individual works are bound to stand out for any given visitor, and make a powerful and lasting impact. But there is no single impression to be taken away from the Tate's latest offering — except perhaps that as empire gave way to Commonwealth, something was salvaged from it on both sides. This is not a project that showcases one artist, school or age, or even the taste of one particular collector. Rather, as Nicholas Serota, the Tate's director, says in his foreword to the book, it is "complex and multi-faceted" and encompasses "complicated stories embodied in a wide range of objects" (6). In that sense, it is an altogether scholarly undertaking. It makes a bid to re-contextualise the colonial experience from different points of view, and calls for the readjustment of perspectives, for reassessments, and for wider debates on matters both of history and art. This makes it challenging and valuable in equal parts — and for this reason, as well as on their own merits, both the exhibition and the accompanying book are highly recommended.

Related Material

Bibliography

Crane, Walter. India Impressions, with some notes of Ceylon during a winter tour, 1906-7. London: Methuen, 1907. Internet Archive.

[Book under review] Smith, Alison, David Blayney Brown, and Carol Jacobi, eds. Artist and Empire: Facing Britain's Imperial Past. London: Tate Publishing, 2015. 256 pp. ISBN 978-1-84976-359-2. Pbk. £29.99. (Available at all good bookstores and online here.)

Last modified 10 April 2016