The Ashmolean has a major collection of Pre-Raphaelite drawings and watercolours. There is only one snag: because these precious items need to be protected from strong light, they are seldom displayed. Now, however, we have a chance to see a hand-picked selection of them in the idyllic setting of the Watts Gallery, Compton, in the Surrey Hills. And here, where they will stay for just a few months, in rooms kept suitably dimmed, they really do shine like treasures.

Significantly placed by the entrance to the exhibition is John Everett Millais's Ruskin (Sketch for a Portrait). With a few quick strokes of the pencil, here is the very conception from which the striking full-length portrait of John Ruskin would emerge, the one that shows the Pre-Raphaelites' patron, critic and fellow-artist, standing by a waterfall in a craggy Scottish valley. You see the composition as it sprang from Millais's mind, translated for the frst time into artistic form. Nearby is Ruskin's own delicate Fleur-de-lys, a timeless example for art students in its fine detail and heraldic presence. Another gem, at the centre of the main wall of this room, is Sir Edward Burne-Jones's Hope, making an interesting contrast with G. F. Watts's oil-painting Hope in the main gallery. Millais doubtless knew of Watts's canvas; Watts was a friend of the Pre-Raphaelites if not actually a member of the Brotherhood (and several of his drawings do appear in the exhibition). But Millais approached the subject in his own way. Rather than clinging blindly to the last shred of hope, Millais's figure rises, eyes open wide and arms reaching upwards, from the depths of the tomb. The chance to see these two works in close proximity is rare indeed.

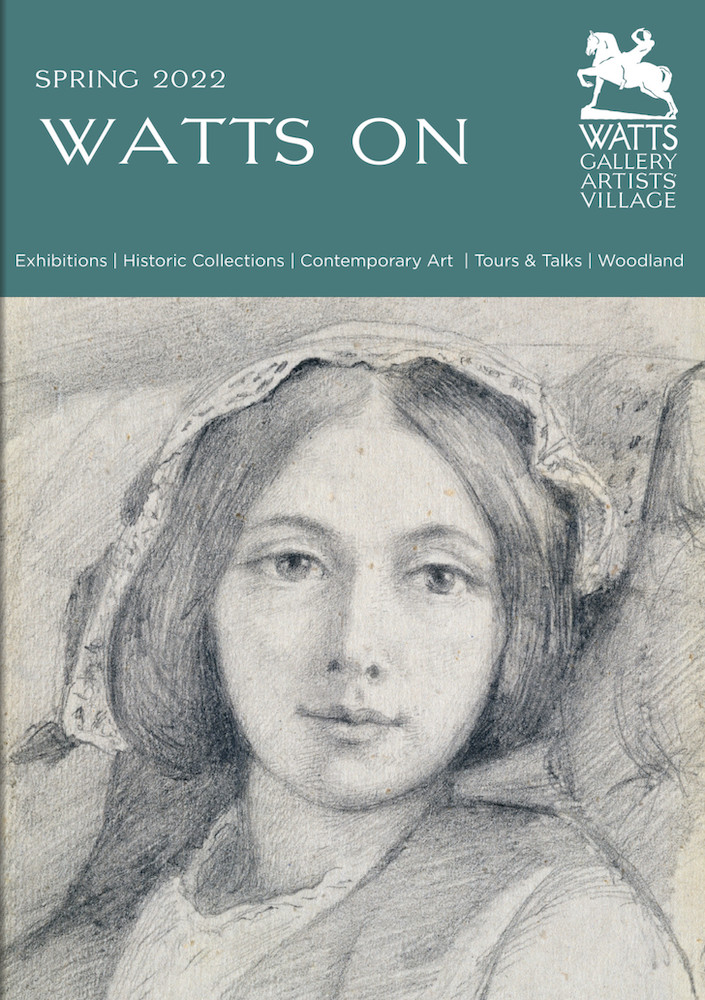

Left: Millais's Mariana. Right: Marie Spartali Stillman's Cloister Lilies.

Two of the other highlights of the Ashmolean collection catch the eye in this first room. One is Henry Wallis's tiny portrait, almost a miniature (just 11.9 x 9.1 cm), of George Meredith's first wife, Mary Ellen. Wallis fell in love with her, and her adoring gaze suggests that the feeling was reciprocated. That gaze makes her the perfect poster girl for the exhibition. The other highlight, just at the top of the short flight of stairs down to the main exhibition gallery, is the set of illustrations of the Moxon Tennyson — Mariana, for instance, positively wrapped up in her own despair: "My life is dreary,/ He cometh not." Here again is proof of Millais's ability to evoke mood not only from expression, but from posture and background; proof too that illustrative work could be also be great art. These small-scale pen and ink drawings, in all their subtle details, as well as their compositional skills, opened the way for a golden age of book illustration.

So far, women artists have been represented only by Elizabeth Siddal's rough sketch, Two Men in a Boat and a Woman Punting. But the lower gallery presents two very accomplished watercolours by women: Elizabeth Fortescue Brickdale's tender depiction of The Childhood of our Lord, and Marie Spartali Stillman's Cloister Lilies. The former focuses on the mother's face and hands as she holds her son close, cupping his chin protectively; but the child, while resting one hand on her lap, looks straight ahead. His lips are slightly parted, his expression hovering between wonder and sorrow, as if he is conscious of the great task before him. Cloister Lilies also captures a moment of spiritual reflection, as a beautiful young woman ponders a future set apart from the general experience of human life. More work by women artists would have been welcome, but these were excellent choices.

Left to right: (a) Ruskin's Velvet Crab (as shown sideways on our own website). (b) Edward Burne-Jones's Study of a Woman's Head, turned to the Left. (c) Burne-Jones's design for the frontispiece of The Golden Legend.

The Pre-Raphaelites liked to experiment with different materials to gain their effects. White paper, the trusty pencil, pen-and-ink, and run-of-the-mill watercolours, were not the only options. Ruskin banished drabness from the grey-blue paper of Study of a Velvet Crab with a range of varied tints, helping to impart to it, as well as to the crab's carapace, an almost plush mother-of-pearl effect. On the other hand, the buff card background of Study of the Plumage of a Partridge> is entirely plain, save for the merest shading by the lifeless bird's head and legs. Nothing was to detract from the fine patterning of the feathers here. The shimmering effect of Burne-Jones's Study of a Woman's Head, turned to the Left, comes from his use of red and black chalks on paper with a pronounced texture, producing a soft, stippled effect — the wonder is that he still managed to convey outlines of the woman's shoulder and profile quite sharply. He enhanced Hope by a different method, using metallic gold paint.

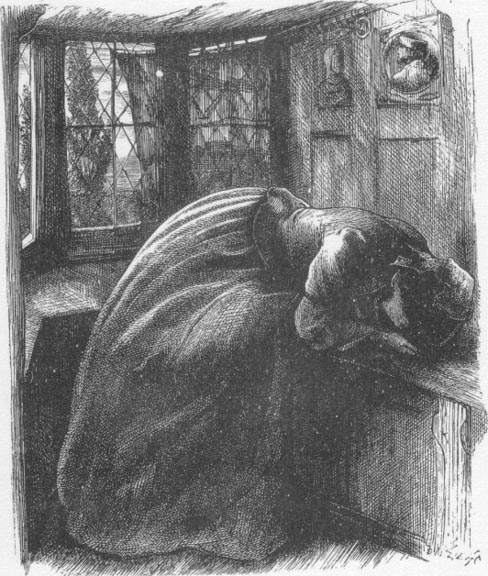

Not only do materials differ from one work to another, but the intended use: in the main exhibition hall are designs for lunettes (by Millais again, for his first commission); cartoons for stained glass (Burne-Jones's musician angels for Lyndhurst church, one playing a portative organ, the other a small harp); and, safe in a glass case and not to be missed, next to Watts's Studies from a Story by Boccaccio, an album of drawings by Burne-Jones, open at his design for the frontispiece of The Golden Legend. This was one of the productions of William Morris's famous Kelmscott Press. Few will want to pass up the opportunity to see a whole page of Burne-Jones's angels.

Left to right: (a) Simeon Solomon's Two Acolytes Censing. (b) John Inchbold's Wooded Slope with Four Figures. (c) Rossetti's portait of Jame Morris in !celandic Costume.

Every facet of the Pre-Raphaelite movement is celebrated here. A knight and his lady appear in Dante Gabriel Rossetti's St George Slaying the Dragon, the knight, it seems, only just preempting his hungry adversary. The medieval strain is married with keen attention to the natural world in Arthur Hughes's The Knight of the Sun, in which the dying man is carried by his faithful followers to see one last sunset. Landscape itself is well represented by works like John William Inchbold's Wooded Slope with Four Figures: look closely to see the fourth figure here, just emerging over the brow of the slope. It is good to see more attention being paid to this artist. Among the religious subjects are two memorable ones, Simeon Solomon's Censing Acolytes and William Holman Hunt's Study for the Lantern in The Light of the World. As for portraits, besides those already mentioned, two stand out. One is Millais's portrait of Ford Madox Brown as a young man, looking away while reading, with an expression that perhaps hints at his ambivalence towards the Brotherhood at this stage; the other is Rossetti's, of Jane Morris dressed up in an elaborate Icelandic costume, after one of William Morris's visits to Iceland.

This selection of the Ashmolean's "treasures" is so inspiring. As an introduction to the Pre-Raphaelites, their interactions and individual achievements, it could hardly be bettered (except perhaps by the inclusion of more women artists). They were not as much a group apart as it might seem: in bringing home to us their willingness to experiment with different materials, mediums and subjects, the exhibition shows them to be as relevant today as ever. Best of all, perhaps, it sends us off to see how certain studies and sketches informed the finished paintings — and, of course, to explore the many other works that make these artists so popular today.

Further reading

Payne, Christiana, with essays by Fiona Mann and Robert Wilkes. Pre-Raphaelite Drawings & Watercolours. Oxford: Ashmolean Museum, 2021. [An indispensable guide to the subject.]

Created 24 March 2022