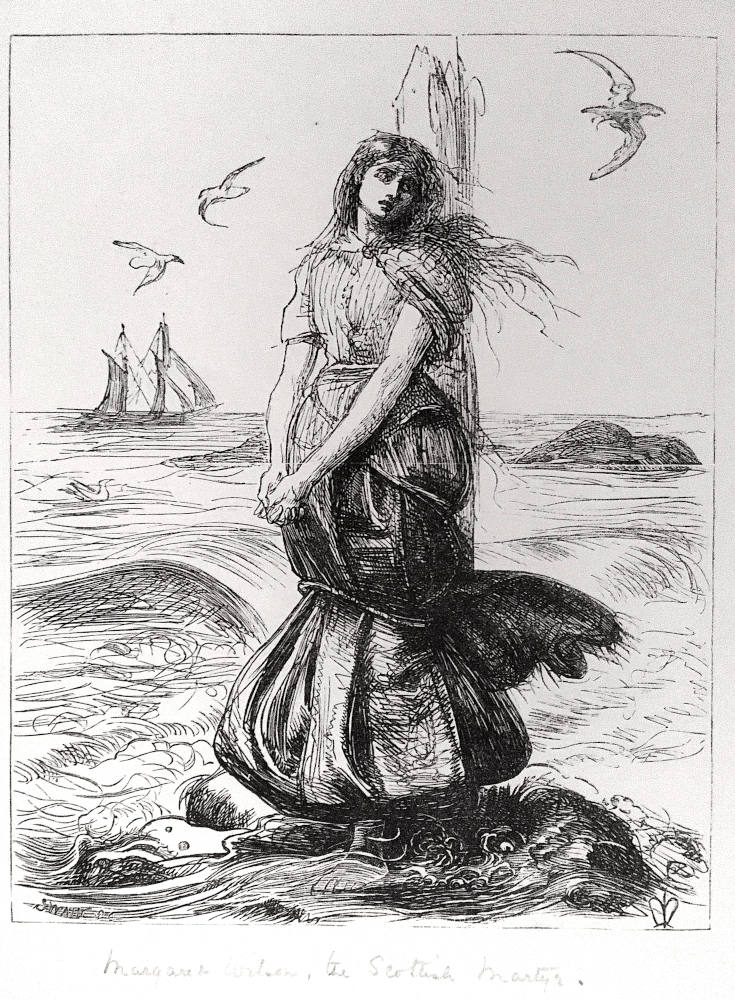

Study for Margaret, Scottish Martyr by J. W. Waterhouse, c.1875. Watercolour on paper, 107/8 x 93/8 inches (27.5 x 23.9 cm) – image size. Private collection. Click on image to enlarge it.

This watercolour is a study for an early work entitled Margaret, Scottish Martyr that Waterhouse exhibited at the Dudley Gallery , Winter Exhibition in 1875, no. 62. Margaret Wilson (c.1667-1685) was a teenaged Scottish Covenanter from Wigtown in Scotland who, along with Margaret McLachlan, was executed by drowning because they refused to swear an oath declaring James VII of Scotland (James II of England) as head of the church. The two became known as the Wigtown Martyrs but Wilson became the more famous of the two because of her young age at the time of her death. On May 11, 1685 the two women were chained to stakes on the Solway Firth and allowed to drown as the tide rose, despite having been given a reprieve by the Privy Council of Scotland.

John Everett Millais most famously treated this subject, initially in a wood engraving published in Once A Week, Volume VII, on July 5, 1862, page 42. In 1871 Millais did an oil painting of this subject entitled The Martyr of Solway that is now in the collection of the Manchester Art Gallery. Waterhouse was obviously inspired to paint this subject based on Millais’ examples, but was more influenced by the early print than the later painting.

Left: Margaret Wilson. 1862. Wood engraving, 5 1/16 x 4 inches (12.8 x 10.2 cm). Private collection. Right: The Martyr of the Solway. Oil on canvas, Source: The Life and Letters of John Everett Millais II, 14.[Click on images to enlarge them.]

The subject is an interesting choice by Waterhouse since by the mid-1870s he was already primarily painting classical subjects. It reflects Waterhouse’s life-long interest in the connection of women with water. The landscape background of this painting is very similar to that seen in Miranda that Waterhouse exhibited at the Royal Academy in the same year 1875. Margaret, Scottish Martyr predates St. Eulalia of 1885, his most famous rendition of martyrdom in his oeuvre. This watercolour is interesting as well in that it is a very rare survivor of drawings from this early period of Waterhouse’s career. Most of Waterhouse’s drawings that have appeared on the market are late, after 1900, and derive from his wife’s sale of his drawings held at Christie's, London, on July 23, 1926. When Waterhouse moved from his Primrose Hill Studios to St. John’s Wood in 1900 many early drawings were likely either discarded or destroyed at that time. In later years Waterhouse came more and more to depend on working up his designs from preliminary small rough sketches, through a large-scale oil sketch, to the finished painting. Here, however, his preliminary idea for the picture has been carried out in a small watercolour sketch. This sketch is likely close to the finished oil painting although contemporary reviews suggest that in the final version Margaret is gazing heavenward with her hair blowing in the wind rather than looking downward with her hair trapped by her crossed arms. This sketch should allow the final oil version to be easily recognized, however, should it subsequently appear on the market, assuming it has not been destroyed.

When the oil version was exhibited at the Dudley Gallery the painting was extensively reviewed and the reviews were generally favourable. A. W. Rapier, the critic for London Society, commented on the work: “Mr. J. W. Waterhouse’s picture of ‘Margaret, Scottish Martyr’ (No. 62), bound to a stake on the seashore to be drowned by the approaching tide, has much sentiment and refinement, and is certainly not devoid of power. More expression, and that of a more clearly-defined character, might have been thrown into the face; but this is almost the sole objection to be found. The waves break on the shore, not angrily, almost merrily, for the sea is fair and blue, though there is some wind and a little surf, and probably, as night draws on, it will be rough; and Margaret stands, her hair blown by the fresh salt breeze, her face gazing heavenwards. There is no shadow of that theatrical exaggeration which an inferior artist would inevitably have given to such a scene” (560). Not every critic agreed with Rapier, however, about Waterhouse’s handling of the martyr’s face. The reviewer for The Art Journal, for instance, commented that “the artist has given a very sweet rendering of the face of Margaret Wilson” (46). W. M. Rossetti writing in The Academy stated: “Waterhouse, Margaret, Scottish Martyr. This uncommon-looking subject has been painted before; the Scotch girl who, for Cameronianism or some other religious obliquity, was judicially sentenced to be drowned by the flood-tide, and was left, bound to a stake, to perish as the sea rose. Mr. Waterhouse gives us the moment when the tide is just beginning to turn: the waters have ceased to recede, have ceased the brief respite between ebb and flow, and are now laving the heretic maiden’s feet, with lulling, murmuring, terrible caress. The painting is not a strong one, yet pathetic in this its faintest foreshadowing of the hours of slow-growing agony and unevadable death” (486).

Bibliography

“The Dudley Winter Exhibition.” The Art Journal. 15 (1876): 45-46.

Lanigan, Dennis T. “J. W. Waterhouse’s Margaret, Scottish Martyr – A Rediscovery.” The Review of the Pre-Raphaelite Society 28 (Summer 2020): 14-15.

Millais, John Guile. The Life and Letters of John Everett Millais, President of the Royal Academy. 2 vols. New York: Frederick A. Stokes, 1899

Rapier, Alfred Watson: “How the World Wags.” London Society 28 (1875): 559-562.

Rossetti, William Michael. “The Dudley Gallery. (Second Notice).” The Academy 8 (November 6th, 1875): 486-487.

You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.

Created 16 September 2021