Catalogues raissonées and monographs have obvious importance in our understanding of individual artists and their contexts. But in many if not most cases, those catalogues and monographs would never have been written were it not for pioneering exhibitions that permit us to see many of one artist's works in the same place. Even exhibitions accompanied by poor or inadequate catalogues turn out to have had great importance, while those with excellent catalogues like that edited and partly written by Bills promise to change our understandings of an artist and his age.

This catalogue opens with two valuable contributions by Mark Bills: a detailed chronology of the artist's life and works and “‘Death and absence differ but in name’: The Subject Paintings of Frank Holl.” His essay introduces us to the one of the two main genres in which this artist excelled, the other being portraiture, as Bills takes us through his early life, education, and experiences that contributed to his works of social realism set in both city and fishing village, such as The Lord gave and the Lord hath taken away, Her Firstborn, and Newgate, Committed for Trial. Holl had a meteoric career, easily achieving early artistic fame and financial success, dying young at the height of his career, and then being quickly forgotten as his urban realism fell out of fashion, so much so that his daughter, writing decades after his death, scorned some of his finest canvases.

Left to right: (a) The Lord Gave and the Lord Hath Taketh Away, Blessed Be the Name of the Lord. (b) Newgate, Committed for Trial. [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

Since Holl increasingly turned away from the work that had made him famous to paint portraits of the rich and famous, critics (including some in this catalogue) too quickly assume he had done so either because he needed money to pay for his lavish homes or because critics attacked his supposedly old-fashioned work. Bills, however, reminds us that

Holl's move to portraiture appears to be driven by more than one factor, and even though portraits were extremely lucrative and his prolific work rate had an effect in his health, it cannot be seen as a purely financial decision. It should be remembered that his subject pictures also continued to command a value. Leaving Home was based on a 30-guinea commission from The Graphic, “At a Railway station — a Study” (10 February 1872). and became an oil on canvas sold to Henry Hill in 1873 fr 220 guineas. . . . Although he stopped sending subject paintings to the Royal Academy, they were still shown at dealers' exhibitions. [31]

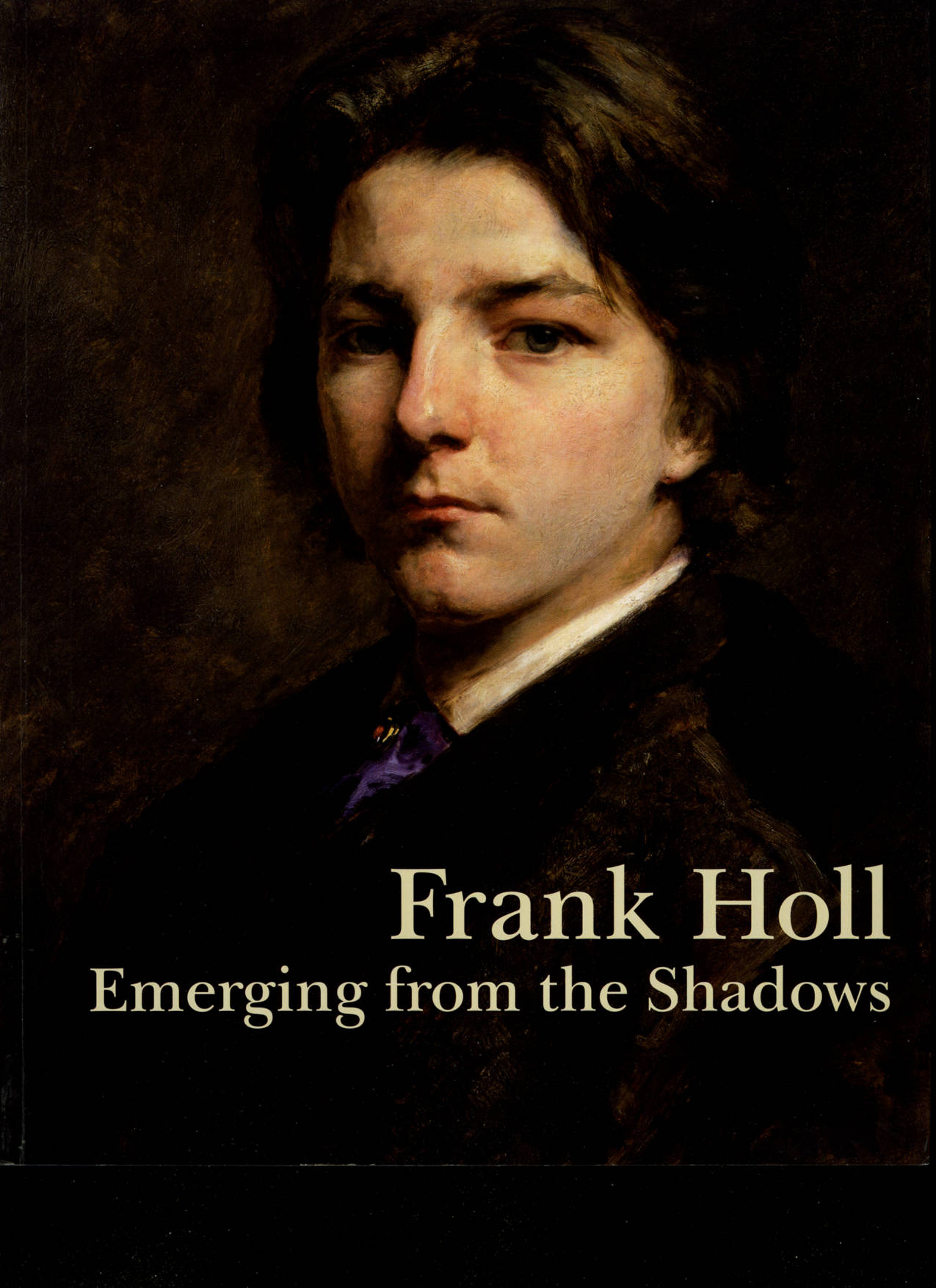

Left to right: (a) Self-portrait. (b) Sir John Tenniel. (c) Sir William Schwenck Gilbert. [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

Peter Funnell's “Frank Holl: Portraits and the ‘Modern Englishman’” which discusses the socio-political implications of Victorian portraiture, also has some interesting remarks about what he terms “Teutonism and its relation to Victorian ideas of manliness.” Since Holl painted comparatively so few portraits of women, one might assume that he was ill suited to painting them — until, that is, one looks at his many successful paintings, not always portraits, of beautiful women and girls. True, Jane Sellars quotes his daughter's recollection of Holl remarking, “Well you know if anything goes wrong, I can't fling my brush at my sitter's head, nor indulge in any bit of strong language to ease my mind a bit!” (83) But of course he couldn't do so either with Gladstone or wealthy clients on whom he depended to pay for his two homes. Since Holl claimed that the hard work of conversation with his client subjects played an important role in each portrait, he either found himself most comfortable with older men or most interested by them. Funnell ranks him with G. F. Watts and John Everett Millais as one of the greatest Victorian portraitists. I can't say that I agree, but then one wants Holl to have a strong advocate like Funnell.

Barbara Bryant's welcome essay relates Holl's career to the two buildings that Norman Shaw designed for him — his lavish London home and studio and his retreat in Surrey — and provides one reason Holl turned increasingly to portraits while it also reminds us of the enormous financial success enjoyed by many Victorian and Edwardian painters. Sophie Gilmartin's “Frank Holl and The Graphic: Sketching London's Labour in Light and Dark” places his major graphic works, such as At a Railway Station and The Foundling in various contexts provided by George Cruikshank , Gustave Doré , and Phiz .

In “A Daughter's Story: Frank Holl and Women,” Jane Sellars argues that

Women play a significant part in the art of Frank Holl. They are the central figures in his subject pictures, which deal almost exclusively with aspects of women's suffering in Victorian society. Furthermore, it is to a women writer [his daughter Ava] that we turn for the most important source of information about his life. [75]

She follows these assertions with interesting observations about Holl's painting in which women and girls appear and equally interesting information about a devoted, if conflicted, daughter who despised Victorian narrative painting and some of her father's best work. Sellars fittingly closes her essay with the following words from Ada: “My love from him was deep and intense, with an admiration which was almost an obsession, but which curiously enough took the form of making me intensely reserved and shy of him, so that neither he not I ever rightly understood the other” (88).

Bibliography

Bills, Mark, et al. Frank Holl: Emerging from the Shadows. Exhibition catalogue. London: Philip Wilson in association with the Watts Gallery, 2013.

Last modified 6 August 2013