If it be true, as true it assuredly is, that all art worth the name must be based upon tradition, it follows that it is needful, for the due appreciation of an artist's work, to ascertain from what sources in the past he derives his inspiration, and to what extent.

Mr. Reginald Frampton began his artistic career as a designer of painted glass windows, but though work of this kind as well as mural decorations still forms a considerable part of his practice, the present purpose is to treat only of his panel paintings, by which perhaps he is better known. Notwithstanding his very strong feeling for form and line, he has never taken up black-and-white work. His decided preference is for colour. At the outset he devoted himself to a great extent to landscape painting, but was led to aim higher than the reproduction of mere inanimate nature after a lengthy stay in France and Italy, and after seeing the magnificent exhibition of the collected works of Sir Edward Burne-Jones. That wonderful display struck Reginald Frampton with the force of a very revelation, opening his eyes to the supreme possibilities of the human form in decoration; and from thenceforward, though some of his most recent work comprises decorative landscape (in which branch indeed he excels), all his larger and more important compositions have been figure subjects.

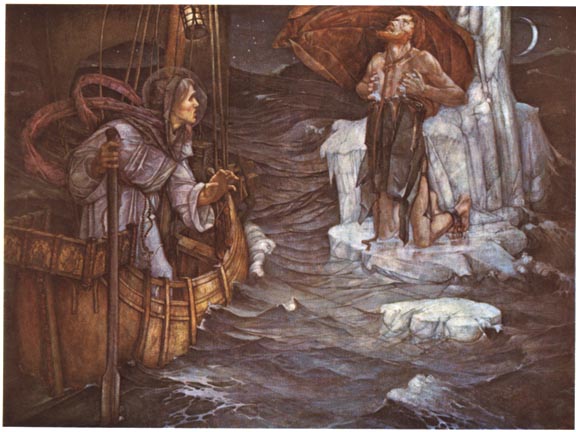

Mr. Frampton considers himself to have been influenced both by primitive Italian painting nd the English Pre-Raphaelite School, and also by the productions of Puvis de Chavannes. But there is, happily, no trace in his work of the sexless wraiths of Angelico on the one hand, nor of the coarse physical type with its thick wrists and ankles, ponderous feet and hands, affected by de Chavannes, the very “French Burne-Jones," on the other. A notable feature of much of the artist's painting is the almost total absence of high lights and cast shadows. Such a mode of treatment, in the hands of a less capable draughtsman, might well produce a painful impression of feebleness or lack of definition. Not so, however, in the case of Mr. Frampton. With him, indeed, this diffused illumination is a matter of deliberate purpose. He adopts a subdued tone from a sense of decorative fitness, his aim being to ensure the flat effect and the subordination proper to mural backgrounds, as distinct from the meretricious illusion of prominent relief and receding distances, which disqualifies the average easel picture from a place in any broad architectonic scheme. Mr. Frampton's compositions, on the contrary, are instinct with a restful and dignified serenity, no less satisfying than transcendental. As typical of this phase of his work may be mentioned a large panel depicting a scene from the legend of St. Brendan. The incident is one with which all readers of Matthew Arnold's poems must be familiar—to wit, St. Brendan encountering Judas Iscariot on the iceberg. The quality of this, picture recalls a forgotten chef-d’oeuvre of Spencer Stanhope's, viz. The Waters of Lethe. The twilight atmosphere is the same in both cases, but there is this difference, that Mr. Frampton surpasses the deceased artist in technical mastery of line and drawing. Mr. Frampton's St. Brendan was exhibited at the final exhibition of the New Gallery, and was awarded mention honorable at the Paris Salon; and might have been acquired permanently for the Dublin Gallery had not those in the position of authority to select unfortunately ignored its very existence. Another work of the artist's, slightly more brilliant in colour-scheme than the last-named, portrays the Holy Grail being conveyed overseas to Smyrna by Sir Galahad and his companions in a boat. This, too, was exhibited at the Paris Salon.

Left: St. Brendan. Right: The Childhood of Perseus. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

With the Voyage of the Holy Grail may be compared another sea subject, in which the infant Perseus, in the lap of his mother, Danae, is depicted afloat in the coffer. Behind Danaé’s head is a wind-blown cloak of red, while the coffer itself is half hidden by mauve draperies. The rest of the composition is in soft tertiary tones.

One of the special features of these and other subjects in which the sea is introduced is Mr. Frampton's characteristic handling of waves — a handling all his own. His nature studies have led him to take a peculiar delight in the sea, and particularly in emphasizing the crisp crest and the curled volute forms of waves in rough weather, as contrasted with the treacherous oily swell of sea-water in comparative calm.

An allegorical work, Navigation, a female figure with ships, orrery in hand, seated on a billow-beaten rock, is a very charming rendering of the subject, and one which exemplifies the above-described treatment of wave-forms.

Left: Our Lady of Promise. Right: L’Enfance de Jeanne d’Arc.. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Our Lady of Promise is a variant of an earlier work entitled Our Lady of the Gothic Tower. In both paintings the Madonna, with her Child, is seated in front of a lofty belfry-tower. The broken classic columns hard by are meant to symbolize the decay and ruin of the old paganism, and the flourishing character of Christianity and its aspiring architecture. A slender tree beside the tower conveys the same message of vigorous growth. The tower in the earlier work is an original combination of Gothic details devised and arranged by the artist himself. In the case of the later work, Our Lady of Promise, here illustrated, the tower is a fairly literal rendering of the south-west tower of Rouen Cathedral, universally known as the Tour de Beurre. The popular explanation of this title, as given, for instance, by Baedeker, is that the beautiful and ornate tower was “erected with the money paid for indulgences to eat butter during Lent." Another account, however, is that the tower was built with the proceeds of market dues on the sale of butter. If this be so, it finds a parallel in the case of a yet more famous building, the Cathedral of Reims. An accidental fire, on July 24, 1481, consumed the outer or span roof of the church over the vaulting, together with the five towers with spires then standing. The flames, spreading to the interior, damaged the building so much that the Archbishop and Chapter were obliged to appeal for funds to the country at large. The then reigning sovereign, Louis XI, helped only with unfulfilled promises. But his successor, C harles VIII, having seen for himself, when he went to Reims to be crowned, how sorely the great church was in need, as his own contribution towards the requisite repairs made over for a teim of years a portion of the royal revenue levied on the sale of salt throughout his dominion. Dues on salt and dues on butter, then, have proved equally serviceable in providing the wherewithal for building purposes. In allusion to the above the artist, indulging his fancy, has placed garlands of buttercups in the hands of the putti who hover overhead.

Another inspiring theme is the childhood of Jeanne d'Arc, Mr. Frampton's version of which has been exhibited in turn at the New Gallery, at Brussels, and at the Paris Salon. One small point, however, seems to have been overlooked by him, viz., that, as Andrew Lang has shown from historical evidence, Jeanne had dark hair.

In the Isabella, the idea which the artist intends to convey is that Isabella, having exalted her devotion to her murdered Lorenzo into a very religion, does not hesitate to set the pot of basil, containing his head, in the most sacred of all places, the very midst of the altar.

Left: Isabella. Right: Johneen. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

The portrait of Mr. John Noble's little boy, Johneen, is not only delightful in itself but is also perhaps less what one might call derivative than anything that Mr. Frampton has produced. Its genesis was as follows. It happened that Mr. and Mrs. Noble, being on a diplomatic visit to Japan and China, bought this costume in the latter country, and finding on their return to England that it exactly fitted their small boy, decided that he should be painted in it. This costume suggested to the artist the idea of carrying out the whole scheme in the same spirit, both in design and colour. "Johneen" is seated on the floor in front of a dark greenish screen on which is “powdered ” the Chinese emblem of Longevity and Happiness. On either side, forming the wings of the screen, are embroidered panels, showing a Chinese landscape with children at play. The artist also designed, and had carved, a special frame for this portrait, Chinese in character, and showing the same emblem. Mrs. Frampton was responsible for the gilding and colour decoration thereon.

In conclusion, a word must be said as to Mr. Frampton’s present technique, elaborated through years of experiment. In picture panels he occasionally uses a tempera background, though he does not actually employ an egg medium. Neither again does he use tube pigments with oil, but powder colours with beeswax, with a spirit vehicle, preferably of petroleum, with copal or shellac. His method is to paint the whole composition in monochrome to begin with, the ultimate colours being applied but lightly, and more in the nature of glazes than anything else. Moreover, he prefers to employ his pigments unblended and not in any continuous expanse, but rather in a series of minute strokes, say of blue, for example, with pure rose-pink touches inserted between the blue when a mauve effect is desired——a process barely distinguishable from that of the ultra-modern Pointillistes. Thus strangely do extremes meet, and the old order, changing, gives place to the new.

Bibliography

Vallance, Aymer. “The Paintings of Reginald Frampton, R.O.I.” International Studio. 66 (1919): 66-76. Hathi Digital Library Trust internet version of a copy in the Cornell University Library. Web. 12 October 2017.

Last modified 12 October 2017