This article appeared in the Art-Journal of March 1863 (see bibliography for more details). It has been transcribed, formatted and linked for the Victorian Web by Jacqueline Banerjee, with the illustrations as close as possible to their original locations. Note that the initial at the beginning, and the three illustrations, are all from the original piece. Click on the latter for more information, and to see larger versions of them. Page numbers are given in square brackets.

EATED on one of the benches provided by the Royal Academy for the temporary rest of weary visitors, the thought has not unfrequently induced us to ask ourselves, after passing round the rooms, and ruminating on the contents of the exhibition — and more especially on the pictures occupying that enviable position, the line, chiefly filled with the works of Royal Academicians and Associates — "where are the men who are rising up to occupy the places of their elders, of those still sustaining the reputation of the British school?" Some of them have almost ceased from toil already, and others, though yet energetic and laborious in their advanced years, and whom we hope to greet once and again in the future, cannot reasonably be expected to continue very long as the active, living exponents of the pictorial Art of England. Of landscape-painters we never need despair; this branch of Art is certain to maintain a high position among us, and yet we cannot point to any one on whom the respective mantles of Stanfield, Roberts, and Creswick — for these artists must be classed under the same head, though differing so widely from each other — might appropriately fall. Who, moreover, is coming forward worthily to fill the positions so long held by Mulready, and still sustained by Webster? Will Sir Edwin Landseer's animals die with him or will some other "master of the hounds" take the field, or another head keeper of equal skill assume the management of the kennels? Will the next generation see the Maclise of its day revelling in scenes of the ages of chivalry, or produce its contemporary Frith, Ward, Dyce, and Herbert? These are queries which, as was just said, we occasionally put to ourselves, and, looking round on the promises for the future, find some difficulty in answering.

Historical painting, in its highest character, seems to be almost ignored by the younger artists of our day; or, if practised, is followed under such conditions as render it far from acceptable, unless to a few whose tastes are more in harmony with that prevailing in medieval times than our own. The best Art, whatever form it takes, is not that which is the work of the hand, but of the intellect; and, therefore, a picture which has little else to recommend it than the subtlety, finish, and elaboration of details, ought never to be regarded as a great work: as the mind makes the man, so also the mind expressed in a picture constitutes its true and real value.

Next to landscape-painting, pictures technically known as genre, or, as they are commonly termed, domestic subjects, seem to promise well for the future; certainly they are much in favour with those artists who aspire to be figure-painters, and are unquestionably most popular with the public. The reason they are so is obvious enough. We are emphatically a domestic people; other nations may equal us in their love of country, but they have not the same for their homes. An Englishman, as a rule, feels pride in his home household, whether he be wealthy or in humble circumstances; his sympathies are in unison with everything which speaks of home-affections, home-influences, home-pursuits. Art, which touches the slightest chord that harmonises with these feelings, he therefore welcomes; and because it does this, its spirit is intelligible to him, though he be unable rightly to criticise the aesthetic qualities of the work, or to give any other reason for the interest he takes in it than that it pleases him.

The Return of the Runaway.

But in discussing, even thus briefly, the probable future condition of the British school of painting, we must not lose sight of our immediate purpose, which is to say a few words respecting the works of a young artist who promises well as a genre-painter. There are, indeed, none of his standing from whom, by careful study and discriminating observation, more may reasonably be expected.

Joseph Clark was born on the 4th of July, 1834, in the small town of Cerne Abbas, about eight miles from Dorchester. He was educated in the latter town, at the school conducted by the Rev. W. Barnes, known as the "Dorsetshire Poet," from whom he received his first instructions in drawing. At the age of eighteen he came up to London, end commenced his studies in the gallery of the late Mr. J. M. Leigh, in Newman Street, where he continued two years, at the expiration of which he obtained admission into the schools of the Royal Academy, and passed through the usual course of study. His first exhibited picture, the "Dead Rabbit," seen at the British Institution in 1857, evidenced at once the class of subject he had determined to adopt, while the excellent manner in which it was treated showed no less forcibly his careful training. Two young rustics have entered an outhouse to feed the rabbit; for one has a large bunch of "green meat" under his arm; but they find the animal dead. The elder of the two holds it up, and both examine it with sad and amazed expression, for it is clear they cannot understand the cause of death. There is, how-[49/50]ever, a vixenish, wiry-haired terrier skulking under the hutch, that looks very like one whom, from circumstantial evidence, a jury would convict of wilful murder.

In the same year he sent to the Royal Academy "The Sick Child," one of those subjects which, however cleverly represented — and this is undoubtedly a really clever picture — can never give unmixed pleasure. In truth, the more merit such a work exhibits in treatment, the less enjoyment does it offer to the spectator, and the artist producing it thereby limits, to a considerable extent, his chances of finding a purchaser. It is clear, nevertheless, that this reasoning had no weight with Mr Clark, who, we presume, disposed of his work; for in the following year he contributed another picture of a similar description, entitled "The Doctor’s Visit." Here, as in the former composition, we have a "sick child," a little boy sitting on a large old-fashioned chair, and propped up by pillows, his face pale and thin, and his whole appearance indicative of the ravages of disease; at his side is the medical attendant earnestly regarding the invalid, while an elderly woman, who may be the nurse, or, perhaps, is the boy's grandmother, waits anxiously to hear the doctor's opinion of the patient. When the picture hung at the Academy, it was so completely overshadowed and overpowered by larger and more brilliantly coloured works surrounding it, as considerably to lessen its attractiveness: yet, notwithstanding these depreciating influences, whoever took the pains to give a little careful examination to the composition, could not fail to admire the vigour with which the figures are presented, their truthful individuality, and the skilful arrangement of light and shade.

The Wanderer.

Out of the sick-room, with all its doleful concomitants, into the open air, the bright sunshine, and everything betokening health and gladness, is an agreeable change even in a picture; and therefore we welcomed Mr. Clark at the British Institution, in 1859, with his "Cottage Door." The tenants of the dwelling are grouped at the entrance, the principals being the mother, who holds an infant in her arms. and the father, who is enjoying his evening's pipe, but has taken it from his mouth for a moment to tickle the child's face with it. The artist has not caricatured his subject, it is most ably rendered in general treatment, and is faithful in expression. In the same year the artist exhibited at the Academy "The Draught Players," a picture which for humour Webster, and for finish Meissonnier might have painted. The following lines were attached to the title in the catalogue: they describe the subject:—

To teach his grandson draughts then

His leisure he'd employ

Until, at last, the old man

Was beaten by the boy.

The scene lies in a cottage: the chief persons introduced are the "players," the old man and the "boy," both seated at a small deal table, the former looking much astonished at his defeat, and the latter, an ill-clad young urchin, whose feet dangle from the rickety chair on which he sits, chuckling heartily over his victory, for he has swept the board of nearly the whole of his antagonist’s pieces, and has "punded" the remainder. The respective characters are capitally delineated — not only those with whom the interest of the subject mainly rests, but all the others as well.

From a game of draughts in a rustic cottage to a game of chess in a well-furnished sitting-room, appears to be a very natural transposition; accordingly, we find Mr. Clark exhibiting at the Academy, in 1860, "The Chess Players," who are a young lady and an elderly gentleman, probably her father; but there is a younger man standing by the lady, with whom she seems in consultation about the next move, as she towards him with one finger on a piece. Her antagonist has, evidently, the game in his own hands; at least, he thinks so, for he looks on with a self-satisfied [50/51] air, his feet crossed, and his pocket-handkerchief carelessly displayed. What we have to remark in this picture as a commendable point in the treatment, is the entire absence of any false sentimentality; there is no attempt at painting up to "exhibition pitch." The young lady and her lover — for there cannot be a question as to the relation in which they stand to each other — are not the creations of some other world than our own, but are people moving in a good class of society, such as one ordinarily meets with. A subject of a very different class to any of the preceding was exhibited with "The Chess Players"; this was "Hagar and Ishmael," which forms one of our engravings on steel this month, and is referred to on the following page.

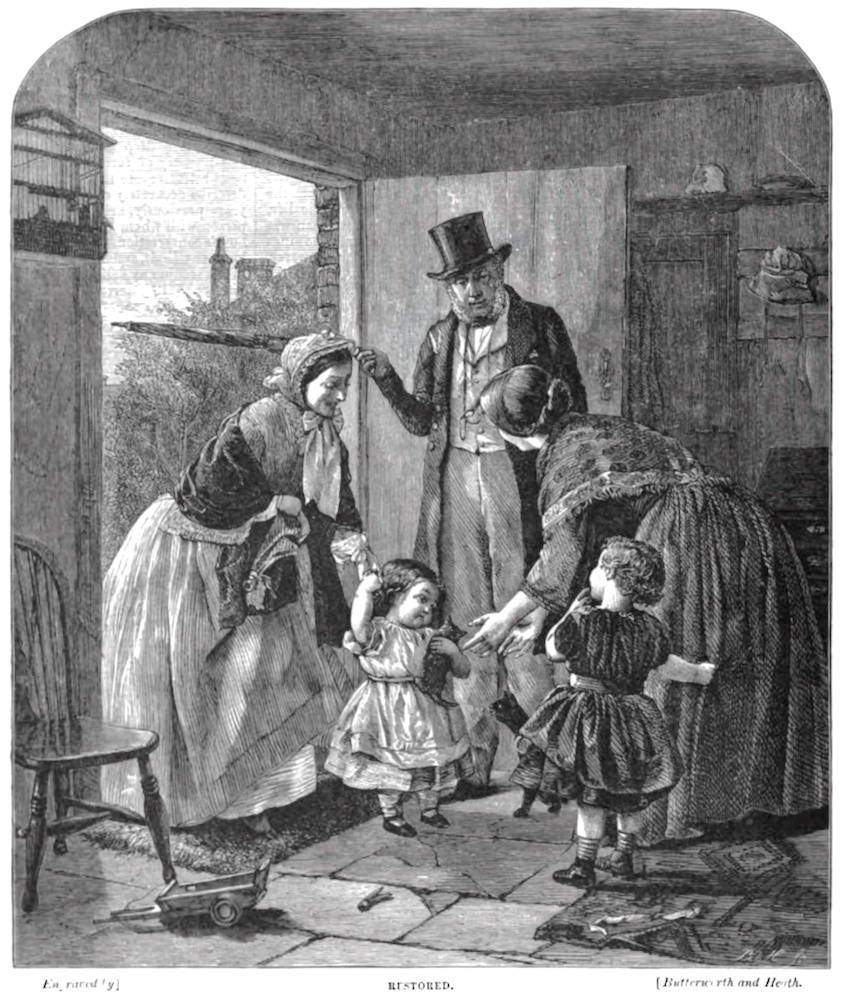

In the year 1861 he sent to the Academy the two pictures engraved on this and the preceding page, respectively entitled "THE WANDERER" and "RESTORED." Both relate to one incident. A little child has strayed away from home, or, as she would probably say, if old enough to talk, she has "taken the kitten out for a walk," and has seated herself at the outskirts of a wood, tempted to enter it by the ripe blackberries on which she has been feasting. There she is discovered by a gentleman and his daughter, the latter of whom stoops down to ask the child some question: this is the subject of the first picture. In the second, the wanderer is restored to its home, the mother welcoming her child, and the old cat her abducted kitten; the gentleman points with his umbrella to the spot where the truant was found. Nothing in the way of Art could be more unaffected and natural than these compositions; both are excellent, but if we have a preference it is for the former, in which the attitude and expression of the three figures, that of the child especially, are truth itself, while the "tree-work" is quite as good in its own way. We hold this to be a perfect specimen of genuine art — as perfect of its kind as could be placed on canvas.

Restored.

"THE RETURN OF THE RUNAWAY," engraved on p. 49 [above], was exhibited at the British Institution last year. Some years have passed since that stalwart sailor went adrift from his father’s home; but he had an inkling for the sea when a boy, for there is a rudely-built ship on the mantel-piece, doubtless his handiwork, and a tattered print of a launch, which probably belonged to him, hangs on the wall. But he has been absent so long his parents cannot recognise him, though the keen, scrutinising look of the mother, aided, perhaps, by his voice, seems as if it more than half detected in the stranger the person of her son: a few minutes more and the discovery will made. Here, again, we have one of those unpretentious subjects, treated with consummate skill and tact, which makes its own appeal to our acknowledgment of truth of Art.

The only other picture exhibited by this artist is "Preparing for Sunday," in the Academy last year. This is also a cottage scene, whose title declares itself; all which our space permits us to say concerning it is, that though not superior to his previous works, it is certainly not below them. Mr. Clark, in point of years, has scarcely got beyond the threshold of his profession, and yet is one whom picture-buyers and the public "look after." He has, if life be granted him, a long and honourable career before him, if he does not rest satisfied with laurels already won. Hitherto he has devoted himself, with a single exception, to one particular class of subject, and presented it only on a small scale. With the qualities he has shown in these minor productions — minor only in size — it is only right to expect from him more important works, even if he limits his practice to domestic compositions. We should, however, like to see him take higher ground, and should have no fear for the result; but whether or not he pleases to do so, and without advocating an obtrusive style of colouring, his pictures would gain immeasurably by a richer display of the pigments he employs: it is only in colour he shows any timidity.

Bibliography

Dafforne, James. "British Artists: Their Style and Character, No. LXIII: Joseph Clark." The Art-Journal Vol. 2, issue 15 (March 1863): 49-51. Internet Archive. Web. 20 November 2024.

Created 20 November 2024