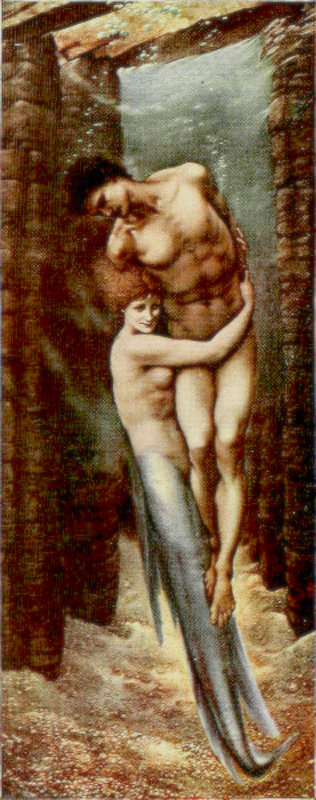

The Depths of the Sea, by Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones (1833-1898). 1881-1898. Oil on canvas. Plate I (frontispiece) in Baldry.

In the text preceding the reproduction, Alfred Lys Baldry writes,

Apart from its technical beauty and its charm of design, this picture has a special interest as the only contribution which the artist ever made to the exhibitions of the Royal Academy. It was shown at Burlington House in 1886, and was painted purposely, during the months that intervened between his election as an Associate in the summer of 1885 and the opening of the 1886 exhibition. In the treatment of the subject there is a touch of slightly grim humour, unusual in the art of Burne-Jones, a humour which finds expression particularly in the face of the mermaid, who drags a human being to her cave at the bottom of the sea without thinking or caring that her sport means death to him. [np]

It is, as always, possible to read the painting in several different ways. The mermaid can indeed be seen as acting cruelly, selfishly or at least thoughtlessly. Violet Hunt had long ago detected in the mermaid's face a "divine sneer" (vii). Looking at Fiona MacCarthy's description of Maria Zambaco's "faintly baleful eyes, well-sculpted nose, neat pointed chin" (208) it is possible to see something in the mermaid's face of the model whom Burne-Jones had found quite irresistible — although MacCarthy also suggests that the artist is commenting here on the kind of society hostesses he was meeting now, who were, in effect, flirting with him, "temptingly fluttering around him, beckoning and flattering, luring him towards a not uncongenial doom" (315). On the other hand, it might seem that the smiling mermaid acts not so much cruelly, selfishly or even thoughtlessly, as ignorantly, without being able to foresee the effect of achieving her prize. That Burne-Jones himself saw it in this way is borne out by the text he supplied for the exhibition catalogue, from Book IV of Virgil's Aeneid "Habes tota quod mente petisti, Infelix," which means something very like the familiar catch-phrase, "Be careful what you wish for."

This is exactly how Edith Nesbit interprets the mermaid's deed in her poem about the painting:

Attained at last — the lifelong longing’s prize!

Raped from the world of air where warm loves glow

She bears him through her water-world below;

Yet in those strange, glad, fair, mysterious eyes

The shadow of the after-sorrow lies,

And of the coming hour, when she shall know

What she has lost in having gained him so,

And whether death life’s longing satisfies.

She shall find out the meaning of despair,

And know the anguish of a granted prayer,

And how, all ended, all is yet undone.

The mermaid will not know what she has done until "the coming hour." A recent critic, too, sees this as a "fatal misunderstanding" on the mermaid's part (Pettit 19).

Perhaps the "grim" element that Baldry detects here comes not from imagining an unpleasant sense of triumph over prey, but from one of the circumstances of the composition. Georgiana Burne-Jones tells us that during this time, both she and her husband lost a dear young friend. Laura Lyttleton, née Tennant (1862-1886), the daughter of the Burne-Jones's friend Sir Charles Tennant. They had greatly enjoyed her company, and had nicknamed her "The Siren" (see Burne-Jones 147), but she died just after the birth of her first child. The mermaid's face, writes the artist's wife, "had some likeness to her strange charm of expression. It was this that Edward meant when, soon after beginning the picture, he said: 'I am painting a scene in Laura’s previous existence.... It is the sorrowfullest ending,' he wrote, 'poor, bright, sweet little thing. I dread knowing any more of people, or watching in a stupid unhelpful way the calamities that rain upon them'” (166). The blighting of this young life, of hope, love and the promise of the future all snuffed out in this untimely way, had clearly been hard to bear, and some of that feeling may well be sensed in the painting. As both art historian and biographer MacCarthy says, people at the time did identify the mermaid with her (see p. 315).

Looking at the completed work, for the realistically watery effects of which he had used a large water-tank borrowed from fellow-artist Henry Holiday, Burne-Jones was doubtful about showing it: "it will be lost entirely in the Academy," he wrote to a friend, adding, "but here it looks like a dream well enough.” For his part, Frederic Leighton liked the painting, although he recalled that Burne-Jones had once "intended to put fishes along the upper edge of the water," but had changed his mind (165). Now, at the last minute, Leighton persuaded him to add them: "I like the idea of the fish up there hugely — they would emphasize the fanciful character which is the charm of the picture, and would bring home to the vulgar eye (a dull orb and a multitudinous) the underwateriness which you have indicated by those delightful green swirls in the background" (165). Burne-Jones duly complied; so Leighton too played a part in the final composition.

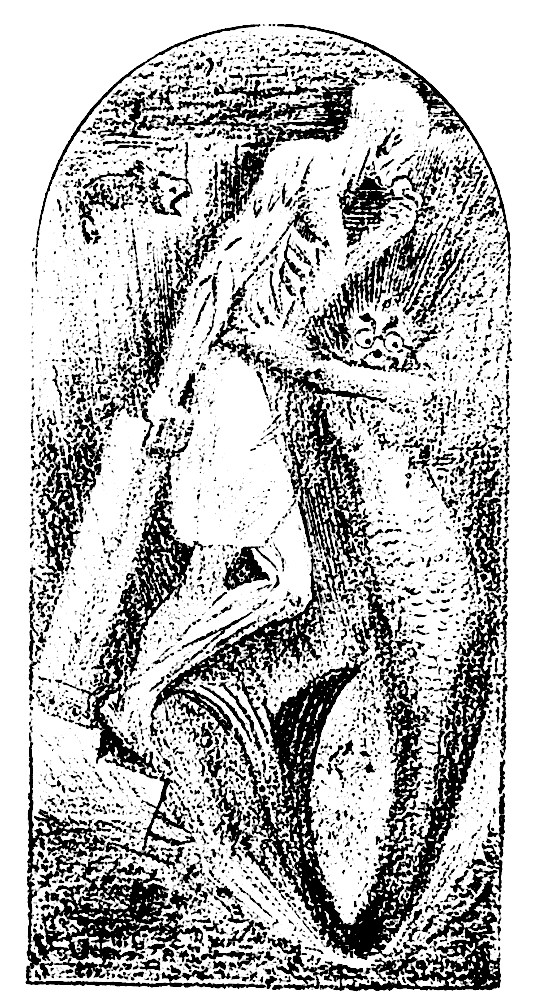

Harry Furniss's comic take on the painting (Furniss 6).

In fact, said Malcolm Bell in 1899, "the delicate tones of this lithe mermaiden swiftly dropping into the abyss with the hapless mariner clasped in her arms were not seen to advantage in the glare and confusion of the Academy walls" (63), and the cartoonist Harry Furniss made fun of it, so that this was the last as well as the first of the artist's submissions to the Academy. Nevertheless, the painting was admired, too: In The Athenaeum's "Fine Art Gossip" column, which would have been written by F. G. Stephens, it was recognised as "a picture of importance, representing a new and difficult subject. It possesses noble and subtle charms of colour, it is finished with extraordinary care." Stephens gets just the right balance in talking about the mermaid: yes, she is an "elvish, mischievous creature," but she "smiles over her victory, and does not know it is in vain" (561). Burne-Jones must have been encouraged. He painted a replica of the oil painting in gouache on wove paper, completed in 1887, and mounted on a panel. This is now in the Fogg Art Museum at Harvard University.

Link to Related Material

Bibliography

Baldry, Alfred Lys. Burne-Jones 1833-1898. "Masterpieces in Colour" Series. London: T. C. & E. C. Jack / New York: Frederick A. Stokes, 1909. Internet Archive, from a copy in the Dorothy H. Hoover Library, Ontario College of Art & Design. Web. 11 March 2025.

Bell, Malcolm. Sir Edward Burne-Jones: A Record and Review. 4th ed. London: George Bell & Sons, 1899. Google Books. Web. 12 March 2025.

Burne-Jones, Georgiana. Memorials of Edward Burne-Jones, Vol. II. London: Macmillan, 1904. Internet Archive. Contributed by Brigham Young University. Web. 12 March 2025.

Furniss, Harry. Harry Furniss's Royal Academy. London: Gainsborough Gallery, 1887. Internet Archive, from a copy in the University of Minnesota Library. Web. 12 March 2025.

Hunt, Violet. The Wife of Rossetti: Her Life and Death. Dutton 1932. Internet Archive. Web. 12 March 2025.

MacCarthy, Fiona. The Last Pre-Raphaelite: Edward Burne-Jones and the Victorian Imagination. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2012..

Stephens, F.G. "Fine-Art Gossip" Athenaeum. 24 April 1886: 561-62. Internet Archive. Web. 12 March 2025.

Created 16 March 2025

Last modified 15 July 2025