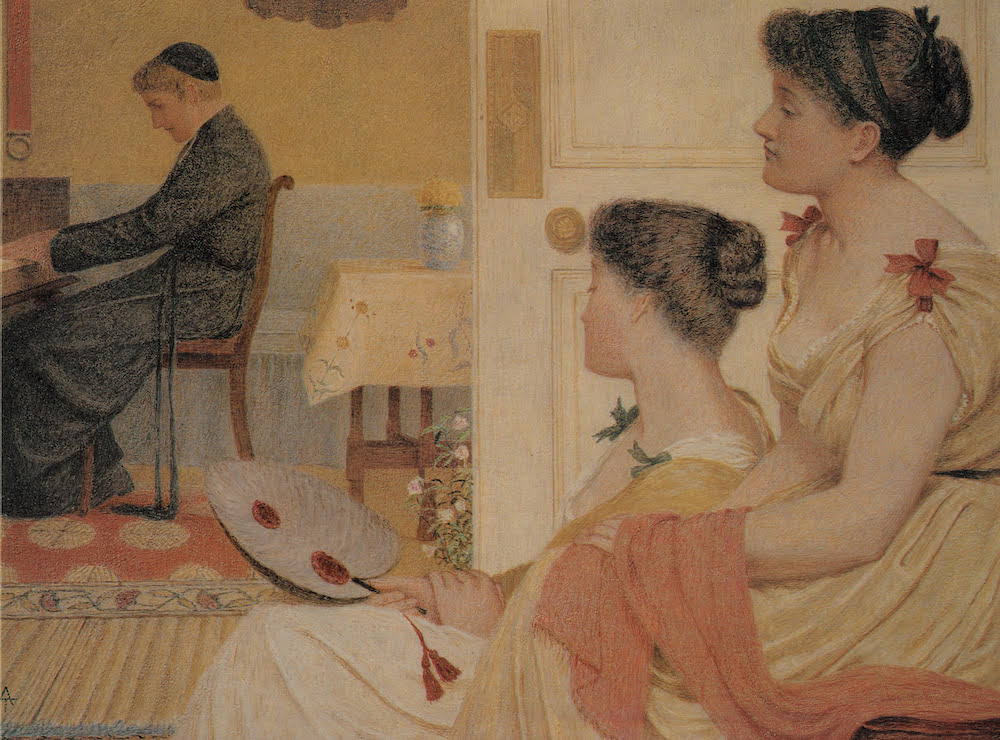

A Music Piece [The Drawing Room], 1871 Pastels and oils on paper; 8¾ x 12¼ inches (22.1 x 31.2 cm). Collection of the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, accession no. WA1963.89.5.

A Music Piece was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1871, no. 544. Sidney Colvin praised this picture, commenting that besides a very charming picture of a winter scene: "A second, and from the artistic point of view, perhaps still more satisfactory piece of this year, is an interior composition, full of delicate adjustments and very pleasant in color, with two girls in easy chairs seated in profile in the foreground, and listening to the music of a priest who sits at his instrument in an inner room" (67).

While this painting was widely reviewed when it was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1871, it generally failed to find favour with the critics. The Architect lumped Armstrong's submissions in with those by members of the Poetry Without Grammar School:

It must not be thought that the Praeraphaelite School has by any means died out; it is fairly represented in the present Exhibition. But there are no longer any signs of the ability and originality which marked the works of those who started the movement. To certain men Praeraphaelitism has been a perfect godsend. Artists who have no genius of their own, and are desirous of attracting attention, gain their object by affecting singularity. They succeed in their object by puzzling the ignorant, and being noticed by those who devote attention to art matters. There is something supremely ridiculous in many of the things that one sees here. Eccentricity, when accompanied by originality, is piquant, but commonplace combined with eccentricity is simply laughable… Mr. T. Armstrong is also an affected artist. His Winter is a most ungraceful and repellent work. There is more feeling in A Music Piece, which is, nevertheless, a flat production" (286).

The reviewer for The Art Journal also found the progressive work of a certain group of young artists to be eccentric:

The room, however, next to it in succession, is the most provocative of criticism in the Academy. Certainly a large part of the pictures in Gallery VII would have been simply excluded from any exhibition in London ten or twenty years ago. And yet these eccentric works are not of a nature to pass under the term Pre-Raphaelite. In fact, since Pre-Raphaelitism has gone out of fashion a new, select, and also small school has been formed by few choice spirits. This anomalous phase is not very easy to define. Perhaps the school, if school it has a right to be called, can be best appreciated by examples which we owe to the talents of Mr. Moore, Mr. Maclaren, Mr. Armstrong, Mr. W. B. Morris, Mr. Barclay, and others… T. Armstrong, in Winter (577), and 'A Music-piece' (544), adapts the principles of the school to northern climes and domestic themes. The Music-piece is not without melody, the lines flow in rhythm. The picture combines that grace in awkwardness, that beauty in ugliness, which the school, ever and anon, affects. [176]

F. G. Stephens in The Athenaeum, however, found the composition elegant and graceful: "A Music Piece (544), by Mr. T. Armstrong, exhibits two ladies listening to a young priest, who plays on a piano-forte: their faces are admirably drawn and expressive; the composition is elegant; and although it is hard to account for the torso of the younger lady, few would complain of such a difficulty in studying a picture which displays so much that is fine in grace, colour, and tone. It is a little painty. Having equally fine sentiment, this smaller work is far better executed than Hay-time, with which Mr. Armstrong, in more ways than one, astonished us the year before last" (693). The reviewer of The Spectator, however, did not care for the surface qualities of Armstrong's paintings: "On the other hand, the pale chalky tints affected by Mr. Moore (and by certain others, as, Mr. Barclay and Mr. Armstrong, who have little of his taste for beauty of line), guiltless, as they are, of any depth or brilliance of color, and strangers to the dignity and tenderness of well-informed chiaroscuro, force upon us a question, can this be that same art of oil-painting, which was practised by Rubens, Velasquez, and Titian?" (704).

This work appears to bear resemblance to the work of three of his friends. As usual the influence of Albert Moore can be seen both in Armstrong's palette and the figures of the two women. The overall composition seems to have been influenced by Simeon Solomon's A Prelude to Bach of 1868 and E. R. Hughes' Evensong that was exhibited at the Dudley Gallery in 1871, the same year as Armstrong's painting. In the other two compositions, however, it is a woman who plays the piano while others listen to the music.

Bibliography

Colvin, Sidney. "English Painters of the Present Day. XXIII – Thomas Armstrong." The Portfolio II (1871): 65-67.

Lamont, L. M. Thomas Armstrong, C.B. A Memoir. London: Martin Secker, 1912.

"The Royal Academy." The Architect V (June 3, 1871): 286.

"The Royal Academy." The Art Journal New Series X (July 1, 1871): 173-80.

"The Royal Academy." The Spectator (June 10, 1871): 704-05.

Stephens, Frederic George. "Fine Arts. The Royal Academy." The Athenaeum No. 2275 (June 3, 1871): 691-93.

Created 19 March 2023