"If you think we're wax-works," he said, "you ought to pay, you know. Wax-works weren't made to be looked at for nothing, Nohow!" — Tweedledum and Tweedledee" in Through the Looking Glass (1871).

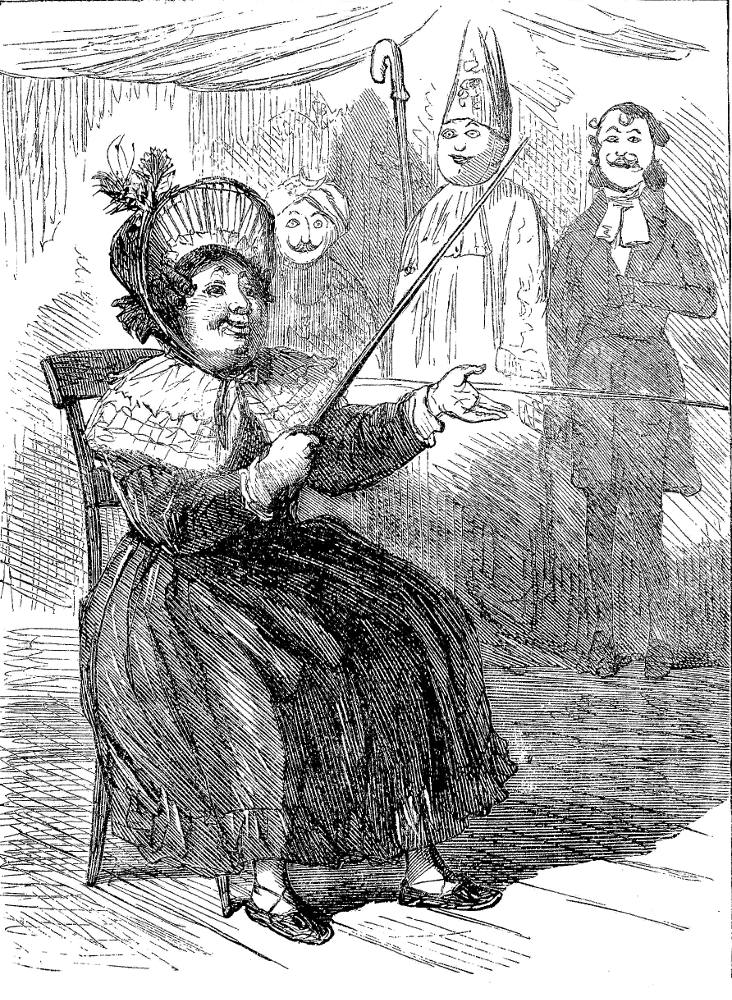

Right: George Cruikshank's description of the dance pavilion at the annual Greenwich Fair Greenwich Fair (8 Feb. 1836).

In 1802, as soon as she could conveniently get out of revolutionary France, effigy-maker Madame Tussaud (1760-1850) arrived in London and began touring with her waxworks exhibit of over one hundred effigies (1808-34). "When she eventually settled in London, her showroom in Baker Street, Portman Square, was a short walk from Dickens's home, from 1839 to 1853, in Devonshire Terrace" (Schlicke, 585). Such travelling exhibitions had been common as educational entertainments at fairs such as Greenwich Fair (which Dickens in Sketches by Boz mentions as having such exhibits) ever since the eighteenth century. Some exhibit halls such London's Lyceum Theatre (1765) were purpose-built for waxworks. David Copperfield, for example, takes Dan'l Peggotty to such an exhibit run by Mrs. Salmon in Fleet Street in Chapter 33. Thus, although today the most famous, Madame Tussaud's mammoth exhibition was hardly Great Britain's first such entertainment. Owners billed their exhibits as educational, featuring the famous and infamous: life-size (and life-like) effigies of statesmen and leading politicians, royalty and revolutionaries, musical composers and playwrights — indeed, any sort of celebrity. In 1867 the cost of admission to see over three hundred effigies at Madame Taussaud's, Baker Street, was six-pence. The 1866 catalogue contains a full description of the Biographical and Descriptive Sketches of the Distinguished Characters which Compose the Unrivalled Exhibition and Historical Gallery of Madame Tussaud and Son, which would have included what Punch Magazine dubbed her "Chamber of Horrors," full of effigies (sometimes depicted in violent and lurid acts) of noted Victorian criminals including the body-snatchers Burke and Hare, apprehended in 1829 and still a byword in 1840.

Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s description of the Lady of the Caravan, Mrs. Jarley (1867).

In the first half of the nineteenth century, travelling shows were generally circuses

or menageries (like George Wombwell's Travelling Circus); panoramic or lantern-slide

shows; waxworks (like Mrs. Jarley's in Dickens's

The Old Curiosity

Shop); or freak shows — some of which became more popular than ever in the

course of the century. At Greenwich Fair in Chapter 12 of

Above: In the 1840-41 serialisation in Master Humphrey's Clock, Phiz depicts Mrs. Jarley's waxworks exhibition, with Nell trying to learn the patter in Mrs. Jarley's Waxworks (Chapter 28, 22 August 1840).

In a late novel, Great Expectations, Dickens's narrator, Pip, compares the cadaverous Miss Havisham to an effigy of a dead notable he had seen exhibited at a fair: "Once, I had been taken to see some ghastly waxwork at the Fair, representing I know not what impossible personage lying in state" (Chapter 8). However, Dickens foregrounds the travelling waxworks entertainment in just one novel, The Old Curiosity Shop, in which a waxworks proprietor, Mrs. Jarley, offers the heroine, Nell Trent, temporary employment as a docent.

Above: In the 1876 Household Edition, Green revisits the waxworks scenes in the 1840-41 serialised novel to rework several of the orginal Phiz illustrations of Mrs. Jarley's caravan and her waxworks exhibition, only spuriously "educational": "That, Ladies and Gentlemen," said Mrs. Jarley, "is Jasper Packlemerton of atrocious memory" (1876). Dickens "almost certainly thought of Madame Tussaud creating Mrs. Jarley, the 'delight of the Nobility and Gentry'" (Schlicke, 587) in the chapters in which he satirizes Victorian popular entertainments such as Codlin and Short's travelling Punch-and-Judy show, and Gerry's performing troupe of dogs.

Dickens in the second number of All the Year Round (1860) in "Our Eye-Witness in Great Company" hailed Madame Tusaud's at her new headquarters in the Marleybone Road as one of London's most popular entertainments. He had referred to her exhibit fifteen years earlier in Pictures from Italy (Chapter 3).

In the cool of the evening: or rather in the faded heat of the day: we went to see the Cathedral, where divers old women, and a few dogs, were engaged in contemplation. There was no difference, in point of cleanliness, between its stone pavement and that of the streets; and there was a wax saint, in a little box like a berth aboard ship, with a glass front to it, whom Madame Tussaud would have nothing to say to, on any terms, and which even Westminster Abbey might be ashamed of. If you would know all about the architecture of this church, or any other, its dates, dimensions, endowments, and history, is it not written in Mr. Murray’s Guide-Book, and may you not read it there, with thanks to him, as I did! [Chapter 3, "Lyons, the Rhone, and the Goblin of Avignon," 13]

Dickens is apparently alluding to the custom of cathedrals to exhibit life-sized, wax effigies of saints interred therein; at Westminster Abbey, this practice extended to the figures of the English kings and queens whose tombs are located in the Abbey. These effigies – made of wax and wood, and lavishly dressed in robes and jewels – were often carried during funeral processions from the fourteenth century onward. The unsurpassed collection of these remarkable but now unknown treasures will be displayed a new museum that the Abbey hopes to inaugurate shortly.

Related Material

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. American Notes and Pictures from Italy. The Works of Charles Dickens in thirty volumes. New York: P. F. Collier, n. d. XX.

_______. "Greenwich Fair." Chapter 12 in Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Chapman and Hall, 1839.

_______. The Old Curiosity Shop. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz"), George Cattermole, Samuel Williams, and Daniel Maclise. London: Chapman and Hall, 1841. Rpt., 1900 in The Authentic Edition.

_____. The Old Curiosity Shop. Illustrated by Charles Green. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1876.

"Greenwich Fair." The Greenwich Phantom — An Intimate Guide to Life in Greenwich.Accessed 13 April 2017. http://www.thegreenwichphantom.co.uk/2008/05/greenwich-fair/.

Schlicke, Paul, ed. "Waxworks." Oxford Readers' Companion to Dickens. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1999. 585-87.

Created 20 May 2020