Much of the following information has been gathered from Frederick and Lise-Lone Marker's in "A Guide to London Theatres, 1750-1880" in The Revels History of Drama in English, Vol. VI: 1750-1880 (1975). They, in turn, consulted H. Barton Baker's History of the London Stage (London, 1904), Allardyce Nicoll's A History of English Drama 1660-1900 (Cambridge, 1966), E. B. Watson's Sheridan to Robertson (Cambridge, Mass., 1926), and The London Stage (Carbondale, Ill., 1962-68). Phyllis Hartnoll's Concise Oxford Companion to the Theatre offers more detailed information about many of these nineteenth-century theatres. Additional images and links added by George P. Landow. For supplementary texts, consult the "Reference List" below.

Adelphi (Strand)

Built in 1806 opposite Adam Street by merchant John Scott (who had

made his fortune from a washing-blue) as the Sans Pareil to

showcase his daughter's theatrical talents, the theatre was given a new

facade and redecorated in 1814. It re-opened on 18 October 1819 as the

Adelphi, named after the imposing complex of West London streets built

by the brothers Robert (1728-92) and James (1730-94) Adam from 1768.

The name "Adelphi" in Greek simply means "the brothers." Among the

celebrated actors who appeared on its stage was the comedian Charles

Matthews (1776-1835), whose work was so admired by young Charles

Dickens. It had more "tone" than the other minor theatres because its

patrons in the main were the salaried clerks of barristers and

solicitors. The Adelphi was also noted for melodramas ("Adelphi

Screamers") and dramatic adaptations, for example, Pierce Egan's Tom

and Jerry, or Life in London, adapted by dramatist T. W. Moncrieff.

Its first notable manager was Frederick Yates (1825-42), and its

longest-tenured manager Ben Webster (1847-71). The well-known Anglo-

Irish dramatist and actor Dion Boucicault performed on its stage in

1860, 1861, 1875, and 1880, while his second wife, Agnes Robertson,

appeared on the stage of the Adelphi in 1861, 1875, and 1893. Noted

adaptor and Dickensian "pirate" Edward Stirling was acting manager in

1838, and stage director in 1839.

Built in 1806 opposite Adam Street by merchant John Scott (who had

made his fortune from a washing-blue) as the Sans Pareil to

showcase his daughter's theatrical talents, the theatre was given a new

facade and redecorated in 1814. It re-opened on 18 October 1819 as the

Adelphi, named after the imposing complex of West London streets built

by the brothers Robert (1728-92) and James (1730-94) Adam from 1768.

The name "Adelphi" in Greek simply means "the brothers." Among the

celebrated actors who appeared on its stage was the comedian Charles

Matthews (1776-1835), whose work was so admired by young Charles

Dickens. It had more "tone" than the other minor theatres because its

patrons in the main were the salaried clerks of barristers and

solicitors. The Adelphi was also noted for melodramas ("Adelphi

Screamers") and dramatic adaptations, for example, Pierce Egan's Tom

and Jerry, or Life in London, adapted by dramatist T. W. Moncrieff.

Its first notable manager was Frederick Yates (1825-42), and its

longest-tenured manager Ben Webster (1847-71). The well-known Anglo-

Irish dramatist and actor Dion Boucicault performed on its stage in

1860, 1861, 1875, and 1880, while his second wife, Agnes Robertson,

appeared on the stage of the Adelphi in 1861, 1875, and 1893. Noted

adaptor and Dickensian "pirate" Edward Stirling was acting manager in

1838, and stage director in 1839.

The Adelphi has the distinction, according to the research of Philip Bolton, of being the first house to stage an adaptation a work by Charles Dickens, the piece being J. B. Buckstone's "The Christening," a comic burletta (farce) which opened on 13 October 1834, based on "The Bloomsbury Christening," which would eventually be published in the first volume of Sketches by Boz. Indeed, many of Dickens's early works were adapted for the stage of the Adelphi, including The Pickwick Papers as W. L. Rede's The Peregrinations of Pickwick; or, Boz-i-a-na, a three-act burletta first performed on 3 April 1837, Yates's production of Nicholas Nickleby; or, Doings at Do-The-Boys Hall in November-December 1838, and Edward Stirling's two-act burletta The Old Curiosity Shop; or, One Hour from Humphrey's Clock (November-December 1840, January 1841).

In 1840, a fresh façade was added, and in 1844 it came under the management of Madame Céleste and comedian Ben Webster, with John Baldwin Buckstone (1802-79) as its principal dramatist. On 28 January 1844, the theatre's lessee, Gladstane, wrote to John M. Kemble, Examiner of Plays in the Lord Chamberlain's offices, for permission to play Edward Stirling's "official" adaptation of Dickens's A Christmas Carol; or, Past, Present, and Future, which opened 5 February. Here, too, on 19 December 1844 Lemon and à Beckett's "official" adaptation of Dickens's The Chimes: A Goblin Story of Some Bells that rang an Old Year out and a New One In opened. In total, à Beckett staged six of his plays at the Adelphi between 1844 and 1853. Still manager in 1848, Ben Webster made application on 12 December to the Lord Chamberlain's office for the licensing of Mark Lemon's adaptation of Dickens's The Haunted Man, to open on 19 December. Ten years later, the old building was demolished to make way for a larger theatre.

In the new building, Dion Boucicault staged The Colleen Bawn (Feb., 1860) and The Octoroon (Nov., 1861), and five other plays between 1853 and 1862: Genevieve; or, The Reign of Terror (June, 1853), Janet Pride (Feb., 1855), George Darville June, 1857), The Life of an Actress (March, 1862), and the immensely popular adaptation of Dickens's The Cricket on the Hearth which Boucicault entitled Dot (which opened on 14 April 1862). Here, too, he produced The Willow Copse five times between 1849 and 1868, Giralda; or, The Miller's Wife (1850-1), O'Flannigan and the Fairies; or, A Midsummer Night's Dream Not Shakespeare's (1850), Pierre the Foundling (1854), She Would Be An Actress (1860), The Lily of Killarney (1877), a revival of London Assurance (1878), Forbidden Fruit (1879), Rescued; or, A Girl's Romance (1879), Kerry; or, Night and Morning (1880), Boucicault staged more plays at the Adelphi than in any other London theatre, the Princess's coming second. In contrast, prolific adapter C. Z. Barnett produced only one play at the Adelphi, Marie (1843), while William B. Bernard produced twenty-two between 1833 and 1863, Samuel Beazley ten between 1829 and 1842, and Thomas H. Bayly eight between 1838 and 1863.

The Adelphi was modernized and redecorated in 1875, and enlarged again in 1887. Its rollicking past was the subject of dramatist E. L. Blanchard's "History of the Adelphi Theatre" in The Era Almanack for 1877; Blanchard himself produced seven plays there between 1874 and 1877. The present building is actually the fourth on that site, and therefore is different from the building described by Charles Dickens in Ch. 31 of The Pickwick Papers (1836).

[Royal] Albert Saloon (Shepherdess Walk, Britannia Fields, Hoxton)

Dating from the 1840s, this theatre was distinguished by having two stages built at right angles to each other, one facing an outdoor auditorium, the other a closed theatre. It specialized in lighter entertainment such as burlesque and vaudeville, but also offered concerts and ballets.

Albery Theatre

Architect: W. G. R. Sprague. 1903.

Alhambra (Leicester Square)

The Central London music hall in one of the City's great entertainment spots began life as the Panopticon of Science and Art in 1854. Destroyed by fire in 1882, the theatre was noted for its Moorish architecture and its equestrian ballet from 1871, when it obtained a licence. Rebuilt, it became a music hall and variety theatre until its demise in 1936. After its demolition, an Odeon cinema was constructed on this valuable Leicester Square property.

Apollo Theatre

Architect: Lewin Sharp. 1901 Shaftesbury Avenue, W1

Astley's Amphitheatre (Westminster Bridge Road)

When retired cavalry officer Philip Astley's old circus ring (built on the site in 1784) burned down in 1794, he replaced it with another, which burned down in 1803. Next, he built a new hippodrome, which staged spectacular dramas under the successful management of Andrew Ducrow. In 1862, Boucicault's dramatisation of an incident in the Sepoy Rebellion, The Relief of Lucknow, was produced here. In 1863, Boucicault renamed the building The Theatre Royal, Westminister, but met with no success. E. T. Smith, succeeding as manager, gave the theatre its old name and scored public acclaim with his equestrian adaptation of Byron's poem Mazeppa. In 1872, George Sanger renamed it Sanger's Grand National, which in 1893 was declared an unsafe structure and subsequently demolished.

The Britannia (High Street, Hoxton)

This working class theatre built on the site of the Pimlico, an Elizabethan tavern, was originally attached to the Britannia Saloon. Sam Lane opened the establishment as an entertainment house which in 1843, after the abolition of the patent monopoly, became home to a permanent acting company managed by the Lane family until 1899. The resident dramatist of this colourful East End theatre was the capable C. H. Hazlewood, noted for his adaptation of Lady Audley's Secret (1863). Famous for its Christmas pantomimes and melodramatic spectacles, it was converted to a movie house in 1913.

The City of London (Norton Folgate)

The City of London Theatre in Bishopsgate, built by architect Samuel Beazley in 1837, "specialized in domestic and temperance melodrama. It was closed in 1868" (p. li). Here Edward Stirling's adaptation of The Pickwick Papers ran through March and April of 1837, and here George Dibdin Pitt's Nicholas Nickleby; or, The Schoolmaster Abroad ran from 19 November through 17 December 1838.

City Pantheon (Milton Street, formerly Grub Street)

Also known as "The New City Theatre" and "The City Chapel," The City

Pantheon began life in an abandoned chapel in 1829.

[Royal] Coburg (Waterloo Road)

The original theatre, built by Dunn and Jones, opened on 11 May 1818, and quickly acquired the nickname "The Blood Tub" by virtue of the sensational melodramas it featured. In 1833, it was renamed "The Royal Victoria Theatre," and is today the home of the Old Vic.

Designed by Rudolph Cabanal of Aachen, 1816-18. Brick and other materials, some of which came from the old Savoy Palace which was pulled down to open the way to Waterloo Bridge. Waterloo Road, London SE1. Until 1833, the theatre was named in honour of Prince Leopold and Princess Charlotte, its original patrons. It opened with a programme including "a melodrama, an Asiatic ballet and a harlequinade" (Weinreb 602), and from 1845 had a 4d. gallery which would be filled with young costermongers and ther like, even including sweeps and dustmen, all taking rowdy part in the performances (see Mayhew 25). But it was also a venue for the more discriminating: "For over a century most of our great actors have appeared within these plain but dignified walls," wrote Arthur Mee in 1937 (654). — Jacqueline Banerjee

Colosseum Saloon (Albany Street, Regent's Park)

Originally opened as a variety theatre in 1837, the Colosseum Saloon was occasionally the venue for plays.

Comedy Theatre

Panton Street (at the corner of Oxendon Street), SW1.

Covent Garden (Bow Street)

Covent Garden has been since the Restoration one of England's chief playhouses. Under its founder and first manager, John Rich, it opened with Congreve's The Way of the World on 7 December 1732, and under the 1737 Licensing Act held the patent monopoly jointly with The Drury Lane for legitimate drama. Although its 1782 alteration increased the auditorium's capacity to 2,500, its sight-lines remained poor until Thomas Harris's rebuilding of 1792. In the 19th c. under the management of the great actor-manager William Charles Macready (1793-1873), it became a leading house in the Shakespeare Revival. When Covent Garden was destroyed by fore ion 20 September 1808, a Neoclassical theatre designed by Robert Smirke Jr. was built at a cost of £ 150,000 in 1809. In 1823, James Robinson Planché developed a series of historically authentic costumes and sets for Charles Kemble's staging of Shakespeare little-played King John, establishing a trend in production design for Shakespeare plays in the 19th c. Planché worked well with the management team of Madame Vestris and Charles Mathews when they came over to Covent Garden from the the Olympic (1839), and continued to work with them here (1839-1842). Under Macready's tenure as manager (1837-39) came the introduction of lime-light long before it was ion regular use elsewhere. Here, too, on 4 March 1841 Dion Boucicault scored his first great theatrical triumph with London Assurance, his script being revised by Charles Mathews (who played Dazzle) and Madame Vestris, the managers at the time. He staged two further plays here: The Irish Heiress (1842) and Woman (1843). After the departure of Madame Vestris in 1842 and the dissolving of the patent monopoly by the 1843 Theatre Regulation Act, the theatre rapidly declined and closed, re-opening on 6 April 1847 as the Royal Italian Opera House, whereupon it ceased to be a home for legitimate drama. After a Bal Masqué on 5 March 1856, the building was again burnt to the ground. On the site of old Covent Garden stands the present-day theatre, dating from 15 May 1858 and designed by Sir Edward M. Barry.

Criterion Theatre

Architect: Thomas Verity. 1874. Piccadilly Circus, W1. According to the theater's own website, "In 1870 following the acquisition of the White Bear Inn site, and adjoining properties between Jermyn Street and Piccadilly Circus, caterers Spiers and Pond commissioned Thomas Verity to design a new development consisting of a large restaurant, dining rooms, ballroom, and galleried concert hall. Having commenced building work it was decided to alter the proposed concert hall (though retaining the composers names, which still line the tiled staircases to this day), to a theatre. . . . The Criterion retains an almost perfectly preserved Victorian auditorium."

The Eygptian Hall, Piccadilly

Architect: P. J. Robinson. 1811-12. Photograph 1895. The Hall, which was torn down in 1905, was at 170/171 Piccadilly.

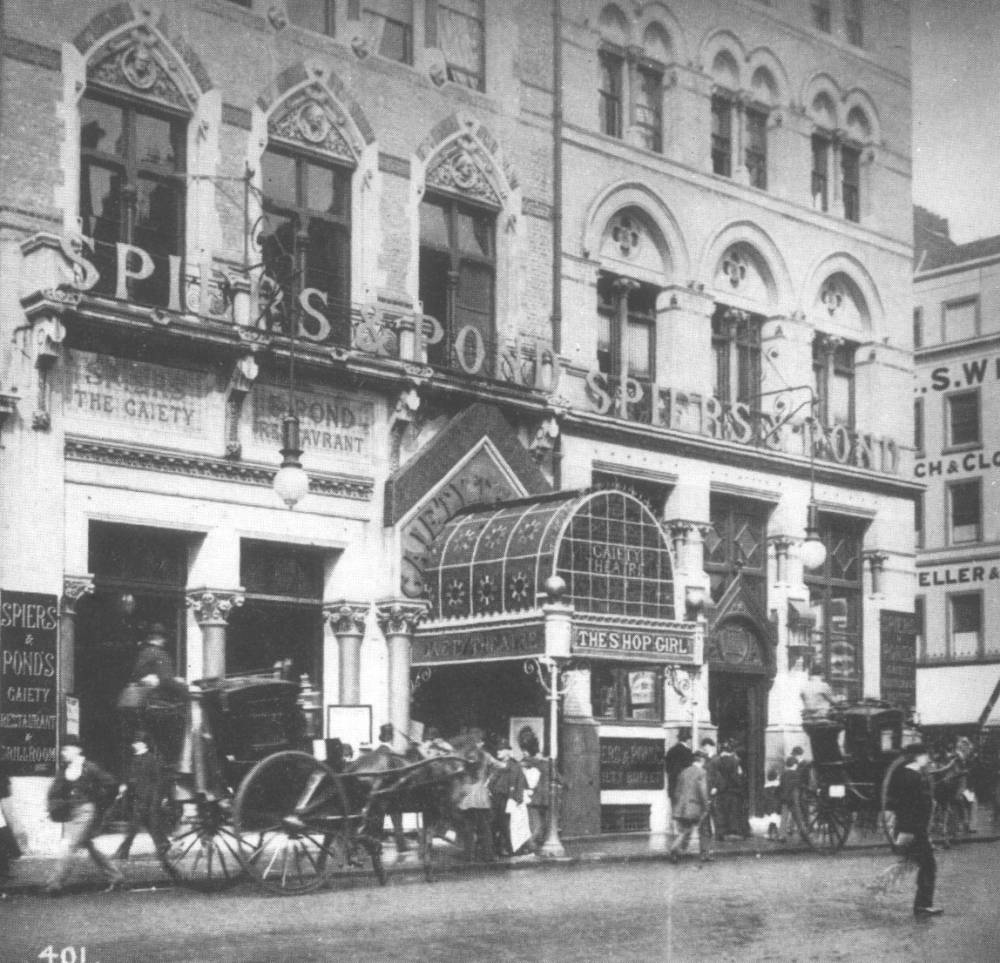

The Gaiety Theatre (The Strand)

This playhouse should not be confused with the New Gaiety Theatre, built for George Edwardes at the corner of Aldwych and The Strand in 1903.

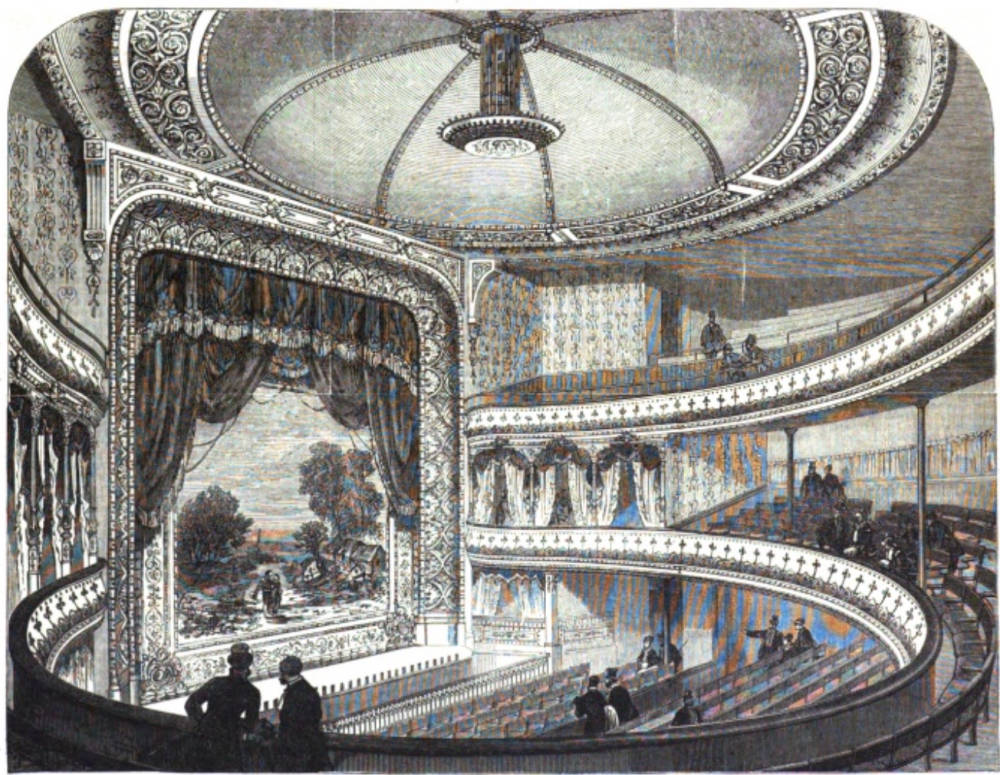

The first Gaiety Theatre, built in The Strand in 1868, was first managed by John Hollingshead with a mixed bill that included W. S. Gilbert's burlesque of the opera Robert le Diable. A distinguished cast including Alfred Wigan and Nellie Farren and outstanding scenery designed by William Grieve won good houses. Here in 1869 Charles Dickens, who prided himself on his knowledge of nineteenth-century London theatre productions, saw his last play before his death in 1870 at age 58, namely H. J. Byron's Uncle Dick's Darling, starring future theatre-great Henry Irving. Here appeared the first Gilbert and Sullivan collaboration, Thespis; or, the Gods Grown Old (December 1871). Dion Boucicault had two plays produced here in the early 1870s, Night and Morning and Led Astray. H. J. Byron's Little Don Caesar de Bazan, starring Edward Terry, Kate Vaughan, E. W. Royce, and Nellie Farren, was undoubtedly a send up of Boucicault's Don Caesar de Bazan. In December 1892 George Edwards transferred here from the Prince of Wales's, bringing with him a new type of show, In Town, the first modern musical comedy, which established the vogue for "Gaiety Girl" productions (so called because they tended to feature the word "Girl" in their titles and always offered choruses full of attractive young women). The theatre's last production was The Toreador (1901), which introduced Gertie Miller to London audiences. On 4 July 1903 the theatre was closed and subsequently demolished. Thus ended the memorable history of a playhouse whose stage had seen such nineteenth-century London theatre notables as Hayden Coffin, Henry Irving, Madge Robertson, Fred Lesley, Charles Danby, John Laurence Toole.

Garrick's Subscription (Leman Street, East)

This theatre dating from 1831 acquired its name from its proximity to the theatre in Goodman's Fields where David Garrick made his London début. In 1846, it burned down and was rebuilt, and in 1851 renamed "The Albert and Garrick Royal Amphitheatre ". Even among East End theatres it was generally hold in low esteem, and from actor- manager J. B. Howe's bankruptcy in 1875 remained empty until 1879. After the success of actress-manageress May Bulmer in the light opera A Cruise to China, the theatre was demolished to make way for a police station.

Garrick Theatre (Charing Cross Road)

Architect: Walter Emden and C. J. Phipps 1899. This late 19th c. theatre was financed by W. S. Gilbert, opening on 24 April 1889 with Arthur Wing Pinero's The Profligate Here Sydney Grundy scored a triumph with the long-running French-style comedy A Pair of Spectacles in February, 1890. Mrs. Patrick Campbell caused a sensation five years later as the lead in Pinero's The Notorious Mrs. Ebbsmith. Afterwards, the theatre suffered a period of decline until 1900 when leased by Arthur Bourchier, whose wife, Violet Vanbrugh, starred in a series of successful productions ranging from straight farce to Shakespeare.

The Globe (Newcastle Street, Strand)

This Victorian Theatre with the Elizabethan name opened in Newcastle Street, The Strand, in 1868. Management changed hands many times as the theatre struggled. Several successful plays transferred here from other theatres helped bring in the audiences: Charles Hawtrey's The Private Secretary from The Prince of Wales's in 1884, and Brandon Thomas's Charley's Aunt from The Royalty in 1892. Badly built, The Globe and the Opera Comique on which it backed were derisively styled "The Rickety Twins." It closed without mishap in 1902. [[Illustrated London News article when it opened]

The Grecian (in the grounds of the Eagle Saloon, Shepherdess Walk, City Road, Shoreditch)

Thomas "Brayvo" Rouse opened this Hoxton playhouse in 1832 as a venue for light opera, legitimate theatre being a Drury Lane-Covent Garden monopoly. In 1844, the stage of the Grecian introduced London audiences to Frederick Robson [the theatrical name of Thomas Robson Brownhill], the actor and ballad-singer who would become the mainstay of the Olympic after 1850. Benjamin Conquest's attempts as manager (1851-79) to stage Shakespeare here proved a failure, but lavish Christmas pantomimes by his son George compensated. In 1872, George Conquest inherited the theatre which his father had rebuilt in 1858, but sold it to Clark in 1879, having spend largely on its refurbishing in 1876. It was sold to the Salvation Army in 1882, and (needless to say) ceased to be a theatre.

The Hackney Empire

Designed by Frank Matcham. Foyer decoration by J. M. Boekbinder; auditorium decoration by De Jong (see Walker 168). Built, like the Coliseum, for Oswald Stoll. Opened December 1901; restored 2001-04. Located at 291 Mare Street, London E8 1EJ. This is one of the finest of the 95 or so new theatres designed by Matcham. Like the almost contemporaneous Richmond Theatre, it was built on a prominent site "with no earlier theatrical associations and no reusable old fabric" (Earl 49) — in the latter respect, it contrasts with the more than 50 additional theatres rebuilt and transformed by the prolific Matcham

The interior of the Hackney Empire, which could hold as many as 1,900 people in its three-tier auditorium (Walker 168; sources vary), boasted state-of-the-art technology for its age. It had electric lights from the beginning, a central heating system, a projection-box that was built in, and even (as at Matcham's Victoria Palace Theatre) provision for sliding open part of the auditorium roof for ventilation. The splendid foyer with its ornate ceiling and windows has a double staircase with marble finishing. Inside the auditorium, there are elegant boxes at the back of the Dress Circle, as well as at each side of the auditorium. As one commentator has suggested, the decor would do justice to a major opera house, let alone a variety theatre (see "The Hackney Empire, 291 Mare Street"). It is hard to make out the subjects of the larger paintings because of the lighting arrangements, though they are clearly, as the listing text says, "of rococo feeling." One smaller panel at the side shows a cherub happily banging a drum. It is all very impressive. — Jacqueline Banerjee

Haymarket, Theatre Royal

The Little Theatre in The Haymarket, built by John Potter in 1720, is the second-oldest London playhouse still in use. The indefatigable Samuel Foot acquired The lease in 1747, and in 1766 gained a royal patent to play legitimate drama in The summer months. Here a number of prominent actors débuted: John Henderson (1747-1785), Robert William Elliston (1774-1831), Charles Matthews Sr. (1776-1835), and John Liston (1776-1846). Demolished in 1820, it was replaced in July 1821 by The current building. Under Webster's management (1837-53) and his successor, John Buckstone, as a great comedy house it hosted most of the great actors of the period. In 1880, The Bancrofts succeeded as lessees.

Her Majesty's Theatre, Haymarket

Her Majesty's Theatre, Haymarket was originally built as the Queen's Theatre by the theatrical impresario, architect, and playwright Sir John Vanbrugh, opening on 9 April 1705. Under the management of Shakespearean- revivalist David Garrick, it underwent no real changes; however, after its destruction by fire in 1789, it was re-built and used extensively for opera. Upon the accession of Queen Victoria in 1837, manager Ben Webster re-named it "Her Majesty's." In the summer of 1837, Samuel Phelps made his London debut here, playing a number of Shakespearean roles, including Hamlet, Richard II, Othello, and Shylock. Over the course of the 1840s, Dion Boucicault had five plays produced here: The Bastile [sic], an "after-piece" (1842), Old Heads and Young Hearts (1844), The School for Scheming (1847), Confidence (1848), and The Knight Arva (1848). In 1853, Robert Browning's Colombe's Birthday, published ten years earlier, ran briefly here. Again in 1867, the theatre was destroyed by fire, and again re-built in the shell of the old structure, to be demolished in 1891 and replaced (though only on one half of its site) by the new building of 1897 which still stands today.

Holborn Theatre

Sefton Parry opened this small theatre in 1866, but it quickly passed through a succession of managers (including Barry Sullivan and Horace Wigan) and went by a succession of names, including The Mirror, The Curtain, and The Duke's Theatre before burning down in 1880. Boucicault produced just one play here: Jezebel; or, The Dead Reckoning (Dec., 1870).

London Coliseum

Volume 34 of of The Survey of London (which British Listed Buildings site has put online) describes the style of this ‘Edwardian ‘Theatre de Luxe of London ’ with richly decorated interiors and a vast and grandiose auditorium” as “exuberant Free Baroque. . . . When built the Coliseum was London's largest theatre with the latest machinery including triple-revolve (disused) and a counterweight system and cyclorama track, still in use, as well as being uniquely equipped with lifts to upper floors. The Coliseum is one of Matcham's finest achievements and very little altered apart from the painting of the exterior.” — Jacqueline Banerjee

London Hippodrome

The London Hippodrome. Listed Building. 1898-1900. Architect: Frank Matcham. Location: 10 Cranbourne Street, London, WC2H 7AG. Built for “Edward Moss for £250,000 as a hippodrome for circus and variety performances” (Bradley and Pevsner). Ri Volume 34 of of The Survey of London (which British Listed Buildings site has put online) describes this Grade II red sandstone “island block of 5 storeys . . . [as] ornate, freely handled French Renaissance with theatrically Baroque skyline . . . [with a] pub front and shops and canopied corner entrance to theatre on ground floor.” Readers who want more than Survey's comparatively brief description should consult the materials in the bibliography below by Roe and other listed online sources plus Wikipedia, which explains that the name hippodrome signifies that animal acts originally provided a large part of the entertainment. This theater also included “both a proscenium stage and an arena that sank into a 230 ft, 100,000 gallon water tank (400 ton, when full) for aquatic spectacles.” In this way, Matcham created "a music-hall and circus combined, complete with water tank for aquatic displays. Perhaps in an attempt to revive the tremendous spectaculars at Astley's Ampitheatre, its purpose was "to provide 'a circus show second to none in the world, combined with elaborate stage spectacles impossible in any other theatre'" (Weinreb 212). One can add that both Bristol and Golders Green (in Greater London) have Grade II listed hippodromes. — Jacqueline Banerjee

The Lyceum (Strand)

Although built in 1765 to house exhibits such as waxworks, London's famous Lyceum Theatre did not become a "licensed" house until 1809, when Samuel Arnold, obtaining permission to stage opera and other musical dramas, renamed it The English Opera House. At a cost of 80,000 pounds he rebuilt The theatre six years later, only to have it destroyed by fire in 1830. On 14 July 1834 a new Lyceum designed by Samuel Beazley opened with its main entrance now on Wellington Street.

The Lyceum, with its "tonier" audience, was associated with adaptations of Dickens's novels and Christmas Books. Edward Stirling's adaptation of Martin Chuzzlewit ran for at least 105 performances from July 1844 through April 1845 here. On 13 December 1845, Mary Ann Keeley, The comic star and The co-lessee of The theatre, applied to The Examiner of Plays for The licensing of Albert Smith's "official" adaptation of Dickens's The Cricket on The Hearth: A Fairy Tale of Home. On behalf of The managers, The Keeleys, J. Thorne made a similar application in December 1846 for The licensing of Albert Smith's adaptation of The Battle of Life, in which The Keeleys played The comic parts of Benjamin Britain and Clemency. Here again Tom Taylor's "official" adaptation of A Tale of Two Cities, with Dickens himself as consultant, ran from January through March 1860, hard of The heels of The end of its serial run and volume publication. "The management of [Madame] Vestris and [Charles] Matthews (1847-55) was highlighted by The scenic marvels created for the staging of Planché's [fairy] extravaganzas" (Frederick and Lise- Lone Marker lv). The theatre's use of spectacular stage effects continued under The management of Charles Fechter (1863-7). In 1866, Boucicault's The Long Strike (his adaptation of Elizabeth Gaskell's Manchester novels Mary Barton and Lizzie Leigh) was produced here. The celebrated Henry Irving starred as the complex villain Matthias in Leopold David Lewis's The Bells (November 1871).

The Lyric Theatre (Shaftesbury Avenue)

The Lyric opened on 17 December 1888, but its first great success came eight years later with Wilson Barrett as Marcus Superbus in his own historical drama The Sign of the Cross (1896). In 1898 Sarah Bernhardt appeared in dramas from the French here. This West End theatre is not to be confused with the Lyric Hall (Hammersmith), which opened in 1888 and became a venue for melodrama two years later before being extensively rebuilt and reopening in July 1895.

The Marylebone (Church Street, Edgeware Road)

The Pavilion Theatre, also known as The Marylebone, was a working-class house noted for its crude melodramas, having opened in 1831 as "The Royal Sussex Theatre." It was demolished six years later, reopening on 13 November 1837 as "The Marylebone." C. Z. Barnett's early Dickens adaptation, The three-act burletta Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress, opened here on 21 May 1838. It was rebuilt and enlarged in 1864, and renamed "The Royal Alfred Theatre" in 1866, but reverted soon afterward to "The Marylebone." In The 20th century it ran under The name The West London Theatre."

The Mirror (see "The Holborn.")

The New City (see "The City Pantheon.")

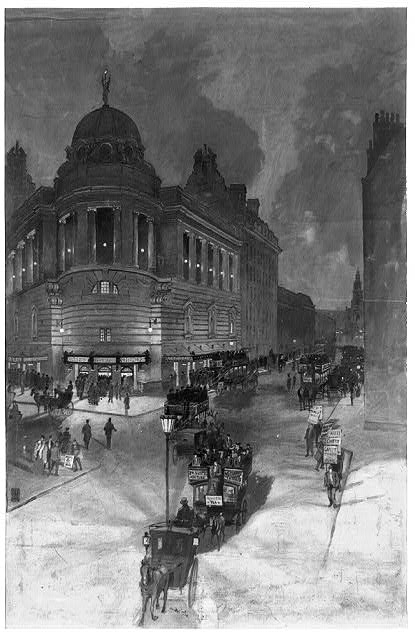

The New Gaiety Theatre

Architects: Ernest Runtz, with elevations by Richard Norman Shaw. 1902-03. Corner of the Strand and Aldwych, WC2. The New Gaiety Theatre was built to replace the original Gaiety Theatre managed by George Edwardes, which had fallen prey to the London County Council's "Strand Improvement Scheme." The architect chosen for the task was Ernest Runtz (1859-1913), not as famous a theatre architect as Frank Matcham, but still one with a very large practice, who designed commercial buildings as well (see "Ernest Runtz & Ford"). But the London County Council found his designs wanting, and called in Richard Norman Shaw to improve on them. Runtz was responsible for the dome on the corner, but it was Shaw who suggested the "flanking high loggia of paired columns and also improved the design of the higher Gaiety Restaurant behind, which faced the Strand." After a chequered history the "powerful exterior of the Gaiety, which Pevsner thought 'Norman Shaw's best design after he had gone classical or Baroque,' was demolished in 1957" (Stamp 65-66). Both the type of building and its style may come as a surprise to those who know Norman Shaw chiefly for his earlier, picturesque domestic architecture.

The New Royal Brunswick (Wellclose Square)

When the East London Theatre was destroyed by fire in 1826, it was rebuilt as the New Royal Brunswick (1828). During a rehearsal of an adaptation of Sir Walter Scott's Guy Mannering, The Astrologer just three years later the entire building collapses, killing fifteen people and injuring twenty.

The New Royal West London (see "The Prince of Wales's")

The New Royalty (see "Soho")

The New (see "The Prince of Wales's")

The Olympic Theatre (Wych Street or Newcastle Street, Strand)

Philip Astley had this playhouse built from the timbers of the French warship "Ville de Paris" (the former deck serving as the stage); as the "Olympic Pavilion" it opened on 1 December 1806. After financial losses, in 1813Astley sold the playhouse to Robert William Elliston, who refurbished the interior and renamed it the "Little Drury Lane" by virtue of its proximity to the venerable patent house. After its rebuilding in 1818, Elliston reopened it with T. W. Moncrieff's Rochester; or, King Charles the Second's Happy Days. John Scott purchased the playhouse at auction in 1826, and gave the building gas- lighting. In 1830, Madame Vestris took over the house, becoming the first female manager in the history of London theatre. Aided by pantomime writer James Robinson Planché, she initiated a series of innovations in costuming and scenery. Here Charles Mathews débuted, marrying Madame Vestris and joining her in the management of the Olympic three years later/ Planché worked well with the management team of Madame Vestris and Charles Mathews at the Olympic (1831-9), and continued to work with them at Covent Garden (1839-1842) and Lyceum (1847-56). After 1839, when the couple left the Olympic to manage Covent Garden, a period of decline set in at the Olympic that was capped by a suspicious fire in March 1849. After a short management by Walter Watts, William Farren took over. Here Boucicault's Broken Vow was staged (1 February 1851) and ten years later Tom Taylor's celebrated social melodrama The Ticket-of-Leave Man, in which the detective (Hawkshaw) was played by Horace Wigan, who was also manager at the time. In its later years, the only celebrity to appear here was Kate Terry (1865-6); the building was demolished in 1889, and a new, much enlarged theatre constructed in 1890. The Olympic closed for good in 1899.

Opera Comique (Strand)

Hastily built in 1870 in the same seedy neighbourhood as the Globe, this theatre was dubbed one of "The Rickety Twins" and, on account of the three narrow thoroughfares at its entrance, "Theatre Royal Tunnels." The most significant theatrical events here were D'Oyly Carte's openings of Gilbert and Sullivan's The Sorcerer (1877), H.M.S. Pinafore (1878), The Pirates of Penzance (1880), and Patience (1881), which was transferred to the celebrated Savoy Theatre later that year. The building was closed for redecoration in 1884, and reopened in 1885; rebuilt in 1895, it closed in 1899 and was demolished in 1902.

Palace Theatre

Cambridge Circus, WC2. Designed by Thomas Collcutt. 1890. Jones and Woodward, who point put that this "huge theatre . . . was orginally planned for the impressario D'Oyley Carte," describe "the grand exterior" as being "in Colcutt's mixed and striped style, mingling bands of red brick and impervious cream faience to disturbing effect" (240). — George P. Landow

The Pantheon (Oxford Street)

James Wyatt commissioned this theatre in 1772 as a sort of indoor Vauxhall, and indeed it was successful as a venue for balls and masquerades before becoming an opera house in 1791. It burned down the next year, and reopened in 1795 with a similar range of entertainments. In 1812 it reopened as the Pantheon Theatre, but, damaged by fire and troubled financially owing to irregularities in its licence, was replaced in 1814 by the Pantheon Bazaar. The building was subsequently the head offices of the London wine-merchants Gilbeys (1867) and site occupied by a Marks and Spencer's store (1937).

The Pavilion (see "The Marylebone").

The [Royal] Pavilion (Whitechapel Road, Mile End)

Wyatt and Farrell opened this home for "Newgate melodrama" in November 1828. Destroyed by fire in 1856, the theatre was rebuilt. Fanny Clifton (Edward Stirling's wife) saw her first success here. Under the management of Morris Abrahams (1871-94) it catered to largely Jewish audiences from the neighbourhood, and its stage saw many Jewish actors.

The Prince of Wales's Theatre (Tottenham Street)

Despite its regal-sounding official name, this very small theatre was nicknamed "The Dust Hole." It was distinguished, however, by the stagecraft and writing of Tom Robertson, who under the management of the Bancrofts in the 1860s produced Caste, David Garrick, and Society.

The Prince's (see "St. James's")

The Princess's (Oxford Street)

This seems to have been Dion Boucicault's theatre of choice for the London productions of his melodramas; over two, he staged nine plays here: The Corsican Brothers (1852), La Dame de Pique; or, The Vampire (1852), The Prima Donna (1852), After Dark, A Tale of London (1868), Presumptive Evidence (1869), and Paul Lafarge, A Dark Night's Work, and the Raparee (1870).

The Queen's (see "Prince of Wales's")

The Queen's (Longacre)

Originally, "St. Martin's Hall," this minor playhouse became a theatre proper in 1867, and closed in 1878. During its short life its capacious stage saw performances by such notables as Henry Irving, Charles Wyndham, Samuel Phelps, Ellen Terry, and Tommaso Salvini.

The Regency [Theatre of Varieties] (see "Prince of Wales's).

Richmond Theatre

Architect: Frank Matcham. 1899. Location: 15 Little Green, Richmond, Greater London TW9 1QJ. Grade II British Listed Building. English Heritage Building ID: 205545.

Royal Alfred (see "Marylebone").

Royal Circus (see "Surrey").

Royal Albert Hall

According to the guide to London published by Charles Dickens's son in 1888, “Albert Hall, Kensington-rd was opened in May, 1871 and is a huge building of elliptical form in the style of the Italian Renaissance, the materials of the façade being entirely red brick and terra-cotta. The larger exterior diameter is 272 ft., interior 219 ft.; the smaller exterior 238 ft., interior 185 ft. The frieze above the balcony was executed by Messrs. Minton, Hollins & Co., and is divided into compartments containing allegorical designs by Messrs. Armitage, Armstead, Horsley, Marks, Pickersgill, Poynter, and Yeames. There are two box entrances -- on the east and west -- with a private doorway from the Horticultural Society's Gardens on the south side, and separate entrances on either side for the balcony, the gallery, and the area, and for the platforms on either side of the great organ. The interior, which is amphitheatrical in construction -- like, for example, the Coliseum at Rome -- is not very appropriate to any purpose for which it is ever likely to be required except musical performances on a large scale. For gladiaorial exhibitions of any kind, the central area, measuring 102 ft. by 68 ft., would, of course, though rather small, be capitally adapted. A bull-fight, even, on a very small scale, might be managed here. As a matter of fact, it is used almost exclusively for concerts, when the area is filled up with seats, and the surrounding tiers, specially constructed with a view to commanding the centre of the building filled with an audience whose entire attention is specially directed to the extremity, where a space has been chipped out for the orchestra, However, it is a "big thing," at all events. At the top of the hall is the picture gallery, capable of accommodating 2,000 persons and used on ordinary occasions as a promenade. There are hydraulic lifts to the upper floors. The hall is 135 ft. in height, and is crowned by a domed skylight of pointed glass, having.a central opening or lantern with a star of gas-burners. Altogether the hall is calculated to hold an audience of about 8,000, The organ was built by Mr. Henry Willis. Them are five rows of keys -- belonging to the choir, great, solo, swell, and pedal organs -- 130 stops, and 10,000 pipes, the range being ten octaves. The orchestra accommodates 1,000 performers. Large tanks are provided in case of fire on the roof of the picture gallery, and supplied with water from the artesian well of the R[oyal]l Horticultural Society, 430 ft. deep.” — Dickens's Dictionary of London 1888, pp. 22-23. George P. Landow

Royal Clarence (Liverpool Street)

Opening as The Royal Panharmonium in 1830, this became a regular theatre a year or two later, when The was altered to The Royal Clarence. It went by a number of names from 1852 through 1867, including "The Regent," "The Argyll," "The King's Cross," and "The Cabinet Theatre."

The Royal Court Theatre (Sloane Square)

Not listed by Frederick and Lise-Lone Marker, this converted Noncomformist chapel, which opened as a theatre in 1870 as "The New Chelsea," made an undistinguished start (even under The name "The Belgravia") until Marie Litton took over its management and renamed it "The Royal Court" on 25 January 1871. Here, several of W. S. Gilbert's early plays were staged with some success; and later, a series of Pinero farces, including The Magistrate (1885), The Schoolmistress (1886), and Daddy Dick (1887) were staged. It closed on 22 July 1887. [I'm not sure when the Royal Court Theatre re-opened, but there has been a theatre in Sloane Square with that name for several decades — George P. Landow]

The Royal Italian Opera House (see "Covent Garden").

The Royal Kent (Kensington High Street)

Named after its first patron, The Duke of Kent, this fashionable, 250-seat playhouse operated between 1834 and 1841(?).

The Royal Manor House (King's Road, Chelsea)

Managed by E. L. Blanchard, this theatre operated from 1838 through 1841.

The Royal Sussex (see "The Marylebone").

The Royalty (Wellclose Square)

Defying the 1737 patent monopoly act, Drury Lane actor John Palmer opened this playhouse on 20 June 1787 with a production of As You Like It, but without a proper license it was forced to closeand Palmer arrested! Under the management of William Macready, the Royalty struggled with pantomimes and burlettas. In 1816, it was renamed the "East End Theatre," which burnt down ten years later.

New Royalty (Dean Street, Soho)

Fanny Kelly ran a small theatre in conjunction with her acting school from May 1840; after ten years of struggling to get by with comedy and melodrama, she gave up. The new management changed the name to the Royal Soho, which opened on 30 January 1850; by November, it was "The New English Opera House." Two seasons later, a new company featuring young Ellen Terry opened in the "New Royalty" theatre with little success. The most memorable productions in the theatre's history were Gilbert and Sullivan's short operetta satirizing the law in general and breach-of-promise in particular, Trial by Jury (1875), Ibsen's Ghosts (1891) and The Wild Duck (1894), Shaw's Widowers' Houses, and the celebrated farce Charley's Aunt (1892) by Brandon Thomas. After a distinguished record in the annals of 20th c. London theatre, the theatre closed in 1938; the building was destroyed in the Blitz.

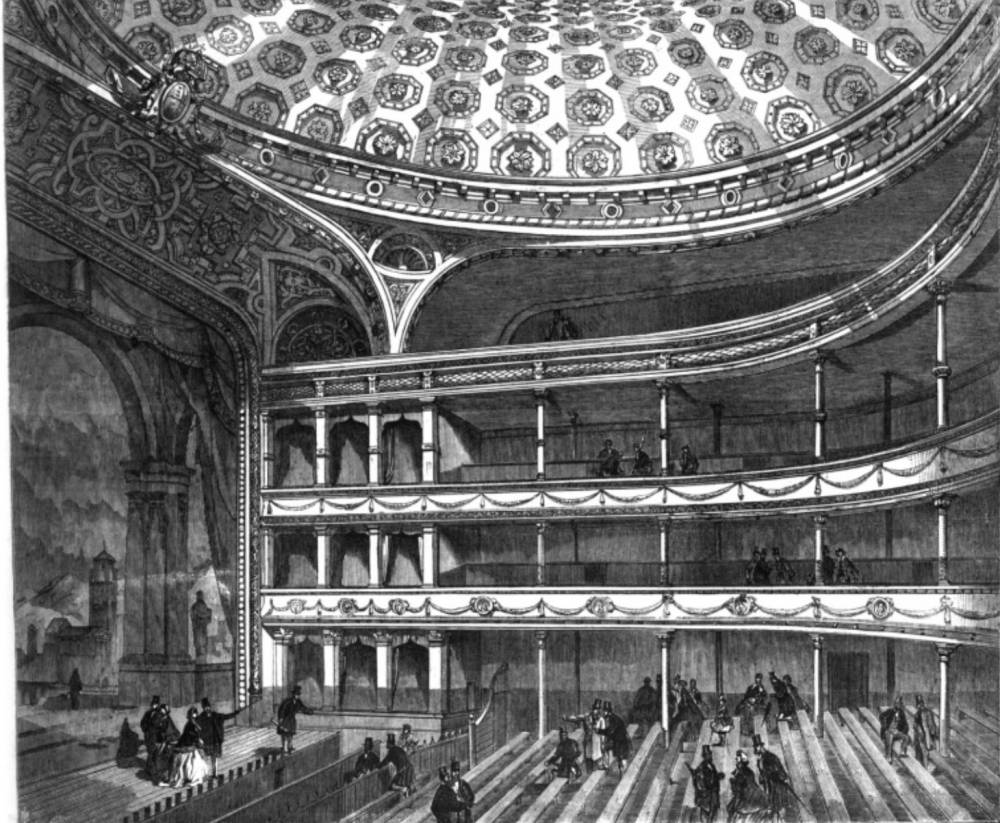

The Royal Surrey (Blackfriars Road, Lambeth)

Probably the best known of London's minor theatres founded in 1771, The Surrey was originally a riding school and exhibition centre, chief rival to Astley's. The owner, Charles Hughes, obtained a licence in 1782, and went into theatrical partnership with Charles Dibdin. At the cost of 15,000 pounds the pair built The Royal Circus, an elaborate theatre in which The pit was replaced by a riding ring. This building burned down in 1803, and was replaced within a year. Under the management of Robert Elliston (1809-14), the ring was eliminated, and the name changed to The Surrey. Here, under Elliston's second term as manager (1827-31) Douglas Jerrold's nautical melodrama Black- Ey'd Susan; Or, All in The Downs (1829), starring T. P. Cooke, ran for over three hundred nights. Here C. Z. Barnett's adaptation A Christmas Carol; or, The Miser's Warning opened on 5 February 1844. Melodramas, especially of the "transpontine" variety, continued to be the Surrey's stock and trade under the management of Shepherd and Creswick (1848-69). Later a cinema, it was pulled down in 1934. [detailed description]

Sadler's Wells

Sadler's Wells (Microcosm of London, Vol 3, 1904 ed. in the Internet Archive, facing p.41).

Mr. Sadler opened one of London's most celebrated theatres on 3 June 1683; initially, it was "a pleasure garden" with a wooden "Music House" and stage. It became known as "Sadler's Wells" because the wooden structure (later known as "Miles's Music House") was built on the site of a medicinal spring. The new owner, Rosoman, had the wooden structure replaced with a stone theatre constructed in just seven weeks. After the second owner's retirement in 1772, the lease was acquired by the Drury Lane actor Thomas King (1772-1782).

In the first four decades nineteenth century, the theatre (known as "The Aquatic Theatre") was used to stage sensational naval melodramas such as The Siege of Gibralter on the surface of a large tank flooded with water from the nearby New River. Just the year after parliament broke the monopoly of Covent Garden and Drury Lane, actor Samuel Phelps became manager, successfully staging Shakespearian revivals over his tenure (1844-62). Charles Webb's adaptation of Dickens's A Christmas Carol was produced here under the new management, continuing the idea of adapting the novelist's works exploited with some success by Thomas Blake's Little Nell; or, The Old Curiosity Ship, which ran here from 11-16 and 18-23 January 1841.

In the meantime, Phelps may be credited with giving Shakespearian production its first permanent home in London. Although he excelled in the Bard's tragic roles, he gave an excellent performance as Bottom in A Midsummer Night's Dream. After Phelps, Sadler's Wells in 1878 was declared a dangerous structure, demolished, and reconstructed. Nevertheless, succeeding managements failed to make a go of it, and it closed in 1906. The present theatre, although refurbished after the Second World War, dates from 1927; since 1934 it has been used exclusively for ballet.

St. James's Theatre (King Street)

Designed by Samuel Beazley for John Braham, this small playhouse opened on 14 December 1835. Here in 1836 Charles Dickens's own play The Strange Gentleman and the ballad-opera The Village Coquettes were first staged. Gilbert Abbott à Beckett's adaptation of Oliver Twist, a four-act burletta, opened here on 27 March 1838. Manager Aired Bunn in 1840, installed a German opera company here, renaming the theatre "The Prince's" in honour of Queen Victoria's new husband. However, in February 1842 it re-opened under its old name. After 12 years of losing money bringing in foreign acting companies and guest stars such as Charles Fechter (1824-79), manager John Mitchell gave up in 1854. In 1863, C. H. Hazlewood's highly popular adaptation of Mary Elizabeth Braddon's sensation novel Lady Audley's Secret starring the theatre's manageress, Louisa Herbert, took London by storm. In 1866, W. S. Gilbert's first play, Dulcamara; or, the Little Duck and the Great Quack was staged; in the same year, Henry Irving scored his first London triumph in Dion Boucicault's Hunted Down (Nov., 1866). Here, also, Boucicault staged his ubiquitous and multi-named The Streets of London (August 1864). Under the succeeding managements of Mrs. John Wood, Hare, and Kendals the theatre was renovated, and redecorated. Pinero's The Squire and The Money Spinner were both produced here in 1881. The St. James's most brilliant period came under the management of George Alexander (1891-1918).

The Savoy Theatre (in the Strand)

The term "Savoyard" (literally, a native of the Italian state of Savoy, then a member of Doyly Carte's acting company, and now generally one addicted to Gilbert and Sullivan musicals) derives from Richard D'Oyly Carte's home for the comic operettas of collaborators W. S. Gilbert and Sir Arthur Sullivan, the series beginning here with Patience at the theatre's opening on 10 October 1881. Frederick and Lise-Lone Marker have omitted the Savoy from their Guide to London Theatres, 1750-1880, perhaps because of the year it opened and perhaps because it was never a venue for legitimate drama, and perhaps because its glory days with Granville-Barker and productions of Shaw and Noel Coward are well outside the Victorian era.

The Strand Theatre (in the Strand, not to be confused with the present theatre in The Aldwych, which dates from 1905)

Originally, "The New Strand Theatre," it opened as a subscription theatre on 5 January 1832 under the management of Yorkshire comedian L. B. Rayner, who had transformed the panorama house on that site into a playhouse. The venture failed, but next January Fanny Kelly re-opened it as a dramatic school, but transferred that operation to the Royalty. Finally, under new management it re-opened on 25 April 1836, and achieved some success running burlesques by Douglas Jerrold, but only in 1848, fully five years after the passing of the new theatres act, did The Strand become the home of legitimate drama.

Theatre Royal Drury Lane

London's preëminent "patent" house was founded by Thomas Killgrew in 1663 under a charter granted by Charles II that conferred upon him a monopoly on legitimate drama; today Drury Lane remains the oldest functioning London theatre. Destroyed by fire in 1672, it was redesigned by Sir Christopher Wren himself and rebuilt in 1674. Garrick, Lacy, Sheridan, and Kemble were the lessees in the eighteenth century, although under the management of the last the old building was condemned and a new theatre built on the same site in 1794. Another fire struck this enlarged theatre in 1809, and new. slightly smaller structure designed by Ben Webster opened on 109 October 1812. In 1833 Alfred Bunn gained control of both Drury Lane and Covent Garden, managing the former from 1833 to 1839, and again from 1843 to 1850. In 1837, actor-manager Samuel Phelps (1804-78) joined the company at Drury Lane, appearing with Macready in a number of Shakespeare plays. Here hew also created the popular role of Captain Channel in Douglas Jerrold's melodrama The Prisoner of War (1842), and of Lord Tresham in Robert Browning's A Blot in the Scutcheon (1843). Under William Macready's brief tenure as manager, significant reforms were put in place as the gifted actor-manager staged Shakespearean productions there (1841-43). Over a twenty-five-year period Dion Boucicault had four plays produced here: The Queen of Spades (1851), Eugenie (1855), Formosa (1869), and The Shaughraun (1875). After a period of decline, the house's fortune's rose again under the management of Augustus Harris from 1879.

Toole's Theatre (William IV Street)

Originally "The Charing Cross Music Hall" (1869), this very minor playhouse hosted J. S. Clarke's revival of Sheridan's The Rivals in 1872, featuring Mrs. Stirling as Mrs. Malaprop, The role that made her famous. Renamed "The Folly Theatre" by new owner Alexander Henderson in 1876, it became a burlesque house. On 7 November 1879 noted comedian and great friend of Charles Dickens, John Laurence Toole (1830-1906), took up the management; after a lengthy tour, he re-opened the theatre in1882 under his own name. Here, Sir Edmund Barrie's first play, Walker, London opened in 1892. After it was demolished in 1896, its site was used for an extension of Charing Cross Hospital.

Tottenham Street Theatre. See "Prince of Wales's."

The Scala Theatre, in Tottenham Court Road, opened as the King's Concert Rooms in 1772, became the Tottenham Court Theatre in 1810, and was renamed the Regency Theatre by new owner William Beverley in 1814. In 1920, the next owner, Brunton, renamed it the West London. His daughter Elizabeth married well known actor Frederick Yates, who starred in a number of the house's productions. In 1831 it reopened as the Queen's or the Fitzroy.

Vaudeville Theatre

Opening in the Strand on 16 April 1870 under the management of H. J. Montague, David James, and Thomas Thorne, it introduced London audiences to young Henry Irving in the role of Digby Grant in James Albery's Two Roses. Here, H. J. Byron's Our Boys (1875) ran four years. Despite its early reputation for farce, its name goes down in theatre annals as the first theatre in England to stage Ibsen's Rosmersholm (23 February 1891) and Hedda Gabbler (20 April 1891). Here noted Dickensian actor Seymour Hicks appeared alongside his wife Ellaine Terriss in a series of Christmas entertainments, including Bluebell in Fairyland (1901).

Vauxhall Gardens

The 17th c. man-about-town Samuel Pepys frequented this theatre when in 1660 it opened as "Spring Garden, Foxhall." Noted for operetta, the house (one of whose occasional patrons was Charles Dickens) was closed after riots broke out there on 25 July 1859.

The Victoria Palace Theatre

Architect: Frank Matcham. Built in 1911 for the variety magnate Sir Alfred Butt (1878-1962). The British Listed Buildings site gives the location as both Victoria Street and Allington Street, Westminster, London SW1E 5 SW1H 0NP. Bradley and Pevsner suggest that the theatre may have reused “walls from the Royal Standard music hall (1886) The front is all ‘Penteliko’ and ‘Keramo,’ white faience products of Gibbs and Canning ” (723-24; quoting without acknowledgment from British Listed Buildings). — Robert Freidus

The Victoria Theatre

This was another of those houses south of the Thames that catered primarily to working-class audiences by providing thrilling melodramas. Located opposite Waterloo Station, it was less than a block away from the Surrey Theatre.

West London. See "Marylebone."

Westminster Subscription (Tothill Street)

This quasi-private theatre opened under the management of T. D. Davenport in 1832. Although it never acquired any sort of licence, several noteworthy players began their careers here. Boucicault's adaptation of Sir Walter Scott's The Heart of Midlothian, The Trial of Effie Deans, premiered here 26 January 1863. This playhouse is not to be confused withe the Westminster Theatre, located near Victoria Station on Palace Street, which opened in 1931.

Wilton's Music Hall, Graces Alley

“Wilton’s is the oldest surviving Grand Music Hall in the world. It belongs to the first generation of public house music halls that appeared in London during the 1850s and which, only fifty years later, had all but disappeared.” John Wilton converted 5 terraced houses into Wilton's Music Hall, which opened in 1858, but its “heyday as a music hall was short-lived: just twenty-two years. Several landlords followed after John Wilton and, in 1880, performances ceased when his final successor was unable to renew the licence due to new fire regulations.” — Wilton's: The City's Hidden Stage

“When it opened in 1859, top acts from Covent Garden would run across town to perform on John Wilton’s stage to an auditorium crammed with up to fifteen hundred revellers, drinking and enjoying the evening’s fascinating entertainment. ‘Champagne Charlie’ who famously drank from a bottle of champagne whilst singing on stage appeared many times at Wilton’s and it was said that the hall was better known than St Paul’s. The pub had beautiful mahogany fittings and became known as the Mahogany Bar (see below).” — “The History” (courtesy Oona Patterson)

Wyndham's Theatre

Designed by W.G.R. Sprague (1899). Location: 32-36 Charing Cross Road Leicester Square, WC2H 0DA. Volume 34 of of The Survey of London (which British Listed Buildings site has put online) mentions this theater's “free classical façade” faced with Portland stone and explains that its “canopy of glass and iron to ground floor” dates from the 1920s. — Jacqueline Banerjee

Related material

- Interior of the New Surrey Theater (1866)

- Victorian London Theater: Dickens on the Right to Amusement for the Working Class

- Theater, Public Spectacle, and Popular Entertainment in The Illustrated London News

Selected Victorian Theatres outside London

Selected Additional References

"The Adelphi Theatre 1806-1900: Bibliography." Http://www.emich.edu/public/english/adelphi_calendar/bib.htm

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis, eds. The Dickens Index. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Hartnoll, Phyllis, ed. The Concise Oxford Companion to the Theatre. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1972.

Leech, Clifford, and T. W. Craik, eds. The Revels History of Drama in English Volume VI: 1750--1880 London: Methuen, 1975.

Rowell, George, ed. Nineteenth Century Plays. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1953; second edition, 1972.

Last modified 20 March 2022