Except for the covers of the two books, the illustrations here have been added from our own website or from the source given at the end. Captions and links have been added by Jacqueline Banerjee. Click on the images to enlarge them, and for more information where available.

Cover of Volume I.

Angus Hawkins' title could not be clearer about the assumption underlying his magisterial biography of Lord Derby: that many educated people asked to name Victorian Prime Ministers will manage at least Palmerston, Salisbury, Gladstone, Peel, Melbourne and Disraeli but few will recall Derby, though he was Prime Minister three times in the 1850s and 1860s and led the Conservative Party for a remarkable twenty-two years. It will be a long time before these two volumes about him, published respectively in 2007 and 2008, are overtaken.

Briefly, Derby was born in March 1799. He (then Edward Stanley) became the MP for Stockbridge as a Whig in 1822 and was appointed Under-Secretary for the Colonies in October 1827 before resigning in January 1828. Grey appointed him Chief Secretary for Ireland in November 1830 and brought him into the Cabinet in that capacity in June 1831. He moved to the Colonial Office in April 1833 but resigned office in May 1834. For the first time he attended a meeting of Conservative MPs in November 1837 although his change of allegiance had been clear for some time before that. He was Colonial Secretary again from 1841 to December 1845, this time under Peel. He moved to the Lords in October 1844 though not at that stage as the Earl of Derby. His resignation as Colonial Secretary was prompted by his hostility to Peel's move to free trade and repeal of the Corn Laws. From 1846 until his resignation on health grounds in February 1868 he led the Conservatives first as the Protectionist party, and later when Protection was abandoned as a hopeless cause and the party had to be held together by other causes. He inherited the title on his father's death in 1851. For eighteen of his twenty-two years of leadership in total his party was in opposition, but he was Prime Minister for a little under four years made up by three spells: from February to December 1852, from February 1858 to June 1859 and finally from July 1866 to February 1868. He died in October 1869.

The bulk of Hawkins' 845 pages is taken up by a detailed account of the events in which he was involved and by a description of his personal and family life but, most obviously towards the end of the second volume, Hawkins also stands back and gives space to reflection on the issues raised by Derby's public life.

Lord Derby's Background and Personal Life

Left: South East Front of Knowsley Hall, drawn by C. C. Pyne (Austin, facing p.29). Right: William Frith's famous Derby Day.

Derby came from a privileged background. The family seat was at Knowsley in south-east Lancashire. They were unchallenged as the most prominent family in the whole of Lancashire and owned 80,000 acres with an average annual income, when he inherited, of about £110,000. His father left debts of £500,000 which he did little to reduce, but he never seems to have been embarrassed by a shortage of funds as were, for example, Palmerston and Disraeli — perhaps because his credit was good. When he became an MP in 1822 after Eton and Christ Church, Oxford, he joined his father and grandfather in Parliament, the former in the Commons and the latter in the Lords. Despite his Parliamentary responsibilities he went with three friends to the United States and Canada on an unusual version of the Grand Tour. They set off in June 1824 partly because his grandfather saw foreign travel as the best hope of ending his relationship with Emma Bootle-Wilbraham, whom he had met at the Knutsford Ballrooms in 1823. While in North America he corresponded with Emma's mother rather than with Emma. He returned in March 1825 as soon as he heard in a letter from his father that his grandfather had relented. He and Emma married in May that year. After that he left the British Isles very rarely. He was a faithful husband committed to his family.

During his third spell as Prime Minister his son and heir was the Foreign Secretary though this was not straightforward nepotism because by then his son had established his own independent political position and his willingness to join his father's government could not be taken for granted and strengthened the government on its liberal flank. His mother heavily influenced his religious outlook and he became and remained a serious-minded moderate evangelical Anglican for his whole life. He took up his grandfather's interest in horse racing and was a very successful owner and breeder for many years. His grandfather had founded the Oaks and the Derby and, in his turn, with others, he founded the Grand National in 1839. He had a strong but insensitive streak of humour which enhanced his popularity in racing circles but was sometimes misplaced, most notably in his humiliation of Disraeli's wife on her one visit to Knowsley in October 1859. Derby was a clever man who, like Gladstone, retained a deep interest in classical authors throughout his life. When he was confined to bed for long periods as was often the case, chiefly because of gout, he kept boredom at bay by translating from the books he had studied at Eton and Oxford. His translation of Homer's Iliad was published in two volumes by John Murray in 1864 to critical acclaim. Gladstone said to the Duchess of Sutherland: Derby "always had in high degree the inborn faculty of a scholar, with this he has an enviable power of expression, and an immense command of the English tongue; add the quality of dash which appears in his version quite as much as in his speeches" (II: 276) The books went through nine British editions and five American editions.

Derby as Prime Minister

Cover of Volume II.

One of the reasons for Derby's being forgotten is that his years of prominence coincided with a period when party politics at Westminster were something of a muddle. His own move from the Whigs to the Conservatives reflects that although he would argue, with some reason, that he had remained consistent and that both the Whigs and the Conservatives had shifted. For much of the time that he led the Conservatives he faced a coalition, sometimes coherent and sometimes not, of Whigs, Liberals, Peelites, Radicals and the Irish. The Conservatives were often the largest party by a considerable margin but rarely, if ever, had an overall majority and so Derby was often seeking to bring into the government individuals such as Gladstone who, although not at the time Conservative, did not lack sympathy with the Government's policy priorities. These efforts generally came to naught. Despite the coalition of 2010 to 2015 and earlier examples in the twentieth century, those who follow British politics feel most at home with a clear cut battle between two main parties, preferably led by a pair of titans.

Derby is a subtler taste. For example in opposition he became a consistent advocate of masterly inactivity as a strategy for the opposition's dealing with the issues of the day. For temperamental reasons this approach was more of a challenge for Disraeli, the leader of the party in the House of Commons. Derby saw more than one reason for the approach. Nothing was more likely to keep together the unstable coalition that he usually faced than fierce opposition from across the chamber. He preferred to encourage the real divisions within the opposition to emerge by lulling them into a false sense of security. Doing next to nothing also reduced the chances of his party having to take policy positions before they were actually in government and thus the chances of their having to take embarrassing u-turns.

He believed firmly that it was safer for the country that change should be brought about by his party than by the other side. He thought that a durable consensus for a new arrangement in any aspect of government was more likely to be achieved around a package that his supporters had shaped because they were naturally less welcoming to change so that, when they accepted it, change was likely to stick. Hawkins gives the impression of approving these methods of opposition and government although no-one could argue that they were obviously successful in Derby's lifetime. His very brief periods as Prime Minister tell their own story. On the other hand it may be that, after Peel's wreckage of the party in 1845-6, no-one could have done better and that he should be judged by how far his style in opposition restrained governments from implementing policies that he would have regarded as very undesirable. Hawkins is also inclined to give Derby some of the credit for his party's very extensive periods in government from 1885 to 1997 though Gladstone's advocacy of Home Rule may arguably have been as important in starting the Conservatives down that road as anything that Derby did.

The two issues he cared about most throughout his political career resulted in failure. His Anglicanism, bolstered by his experience as an Irish landowner - his first married home was on the Derby estate at Ballykisteen, Tipperary – led him to be a fierce defender of the establishment of the Irish church. It was swept away by Gladstone's first administration which replaced his own third administration, by then being led by Disraeli, in 1868.

On the way the country should be governed, he remained true to the values he had learned as a young Whig; this was often expressed in direct criticism of democracy which sounds strange to twenty-first century ears. It is easier to understand if expressed as a sincere belief that the best government would give real weight to the views of the private owners of property. He would argue that they have the public interest at heart and had the experience and motivation to reach sensible judgments. In the rough and tumble of real politics he sometimes seemed to deviate from this course or, at the very least to compromise. He was an important promoter of the Reform Act of 1832 though that was a very modest step towards a more democratic system. After standing against further electoral reform in opposition - in truth when Palmerston was Prime Minister little effort was required to stop it – he committed his party to a new Reform Bill when he came into office in 1866. By the time the Bill was being debated at length in the Commons the increasingly frail Prime Minister could do nothing to determine how far, in the direction he had set, reform should go. Disraeli is widely acknowledged to have managed the Bill outstandingly as the Government's senior figure in the Commons. In the result more men got the vote than Derby had intended but he acquiesced and praised Disraeli with more genuine warmth than he had usually employed over the past many years of Disraeli leading the Commons while Derby led the party.

Hawkins gives a full account of Derby's last major public speech at a banquet in his honour at the Free Trade Hall in Manchester on 17 October 1867. The dinner was attended by 800 local notables with 1200 in the gallery looking on. Derby concentrated on the Reform Act of that year. The tone as well as the content of what he said, as summarised at length by Hawkins, illustrates how a Whig attached to the value of property and who believed that change was best left to him and his supporters was articulating his values by the mid-Victorian period in contrast with what he would have thought and said forty years before:

First, he [Derby] described how his admiration for the intelligence, fortitude, and dignity demonstrated by the working classes during the suffering of the Cotton Famine had shown him they were deserving of the vote. Their reasonableness, sound sense, and lack of social prejudice had convinced him that the working classes could be entrusted with the electoral representation which his government had now put in their hands.... Wage earners, he proposed, had shown themselves to be responsible, loyal, and virtuous. By recognizing and rewarding these qualities, his government had strengthened that mutual respect and essential trust which cemented the nation's loyalty to its institutions. [II: 356-57]

At the November 1868 election the Conservatives in Lancashire did even better than Derby had hoped. He would have been happy with eighteen of the thirty-three county and borough seats within Lancashire; in fact they won twenty-two. This must have reflected Derby's personal standing in the county and probably also gratitude for his response to the hardship of many working people in Lancashire in the first half of the 1860s during the American Civil War. Derby had organised others to help in the face of extreme poverty and hunger and his personal generosity had been on an unprecedented scale. Across the nation as a whole in contrast with Lancashire, the working men, in whom Derby said in Manchester he had been happy to place his trust, rewarded the Liberals led by Gladstone as they used the vote conferred by the reforms that Derby had sponsored. Disraeli resigned without waiting to meet Parliament when the results were known. Although Derby's hostility to democracy was greatly eroded by the end of his life, he never saw the consequent need to organise constituency by constituency in order to win elections. Ironically, in this there was a contrast with Lord Cranborne, formerly Lord Robert Cecil and later the Marquess of Salisbury, who resigned from Derby's Cabinet because of his hostility to the proposals for widening the vote but, when he came to lead the party, strongly encouraged the effort to get out the vote for Conservative candidates and was duly rewarded.

Derby's Character and Achievements

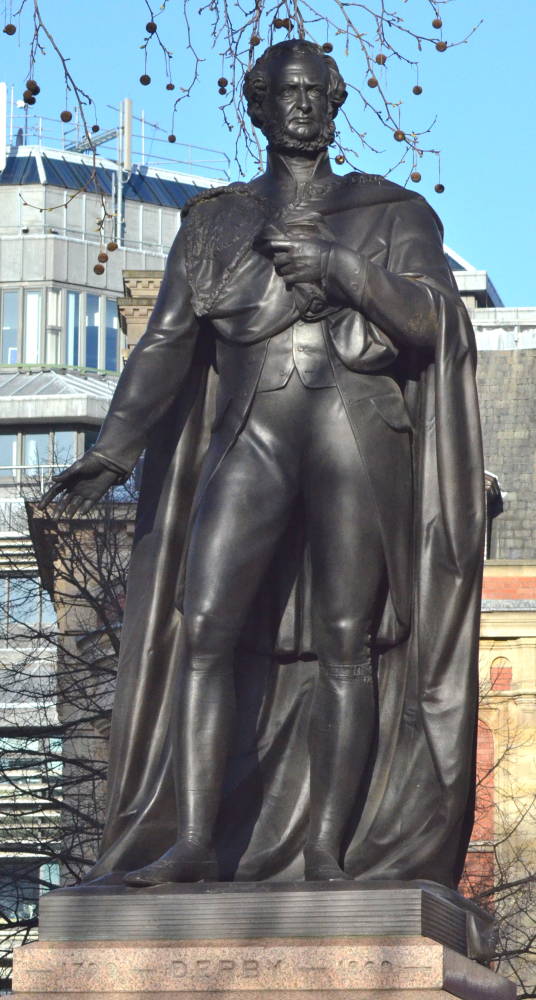

Statue of Derby facing Parliament Square, London.

Derby was an exceptionally interesting person which Hawkins brings out with detail after detail. He was, of course, clever. He was a powerful orator from an early age and gradually his judgement about what to say and what not to say improved. He advised Disraeli, on one occasion, who certainly needed the advice, that he should say nothing and might have added but say it very well. His approach to Ireland developed. In his early years, when it was his Ministerial responsibility, he inclined to coercion and he never became soft on crime and disorder but later he became as displeased with the militant Protestant unionists as he was with O'Connell in earlier years. He came to believe that the best way to preserve the union was to be fair to tenants and Catholics, often, of course, the same people. Later in his political career his party won many Westminster seats in Ireland and he was always keen not to upset the Catholic laity in Ireland and in England. It might be argued that someone else might have got even further but he undoubtedly rescued his party from the crash of 1846 and left it close to achieving the dominance it enjoyed in the late Victorian period and for most of the twentieth century. Hawkins quotes Kebbel as saying that Derby combined the high rank, spotless character, and great wealth of Lord Rockingham with the intellectual force, fervid eloquence, and happy wit of Charles James Fox. His own summary reads:

Derby's cheerful, often teasing, social manner his evident delight in the boisterous company of racing men at Newmarket or among his tenants at Knowsley, his conscientious devotion to the interests of Lancashire, his lightly worn scholarship, his accomplishments as a powerful parliamentary orator, and his dignity as a premier and Chancellor of Oxford University embodied an English aristocratic ideal at the heart of mid-Victorian Conservative sensibilities. [II: 389]

The Jockey Club, Newmarket.

He goes on to identify Baldwin, Macmillan and Butler as firmly in the tradition of Conservatism established by Derby. Derby was not especially long-lived though seventy was a better age than might have been expected given how often he was forced to take to his bed and then recuperate slowly and quietly but it is remarkable that in Boston he met John Adams who had a hand in drafting the Declaration of Independence and brought Cranborne into his cabinet who was still Prime Minister into the twentieth century.

This biography is not a quick or easy read. It is dense and thorough. There can be no better way of learning about Derby and anyone who turns to it will find that, as an added bonus, they understand a great deal more about nineteenth-century England than just the life of its subject. It richly repays the time it takes to read. John Charmley, who is warmly acknowledged, may be a little generous but not excessively so when he is quoted on the cover as describing Hawkins' Derby as the most significant book on Victorian politics in half a century.

Related Material

- Edward George Geoffrey Smith Stanley, 14th Earl of Derby (1799-1869)

- Derby in the House of Commons

- The Earl of Derby (Alexander Ewald)

- The Earl of Derby (Justin McCarthy)

- The Reform Acts

- "Reform rather than Revolution" (Review)

Sources

Hawkins, Angus. The Forgotten Prime Minister: The 14th Earl of Derby, Volume I: Ascent, 1799-1851. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007. 544pp. £49.99. ISBN: 978-0199204403.

_____. The Forgotten Prime Minister: The 14th Earl of Derby, Volume II: Achievement, 1851-1869. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008. 552pp. £60.00. ISBN: 978-0199204410.

[Illustration source] Austin, S., Harwood, C. and G. and C. Pyne. Lancashire Illustrated, from original drawings. London: Fisher, Son, and Jackson, 1831. Internet Archive. Contributed by University of California Libraries. Web. 21 December 2015.

Created 21 December 2015