Victorian heraldry was a microcosm of Victorian middle and upper class culture. Its use could express adherence to the rituals of a dying past, or a romantic harking back to a safely dead one. It could be a way to preserve or to claim status. It could result from solemn study of history, or a playful embracing of the latest fashion. It was wildly popular, then faded from sight with the onset of the Great War.

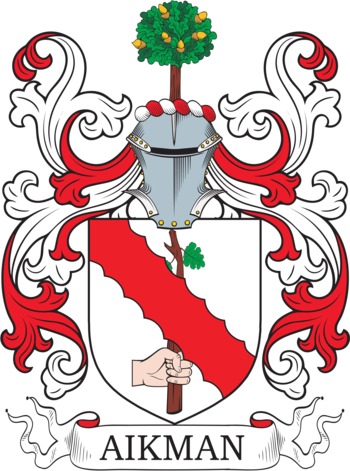

Two coats of arms. Left: Aikman. Right: Landon. [Click on Aikman for an example of an explanation of a coat of arms.]

By heraldry, we mean not just the “science” or its compositional rules and the administration of the rights to coats-of-arms, but also their display. Heraldry is historically important far beyond the martial context because of its social and thus cultural significance. It was, and continues to be, an exclusive form of personal branding. In the British Isles merely to display a personal coat-of-arms is to claim at least gentry status (though in Scotland the requirement was technically “virtuous and well deserving”). In heraldically literate times, it was also a medium for broadcasting genealogical credentials. If a coat-of-arms was “quartered” to reflect marriages between great families, then it could also boast of the owner’s important connections and long lineage.

The precise origins of heraldry are obscure. Though it aided in recognition in war and tournament from at least the mid-thirteenth century, some modern heraldry scholars argue that it derives ultimately from legal seals. Certainly, from early on, it was as important to civilians as it was to professional belligerents. The Early Modern decorative arts reflected this importance, with the arms of friends, family, ancestors and allies featuring on everything from leather trappings through to cathedral ceilings. However, the classicism of the Georgian period rendered heraldry unfashionable, relegating it, for example, to minimalistic displays in the entrance halls of great houses. Heraldry had also acquired unfortunate associations with recusancy, Toryism (in the early eighteenth-century meaning) and Jacobitism. It was just before the start of our era that the Gothic Revival, part of the Romantic movement, freed Heraldry to resume its traditional roles in society, but in a more complex cultural world that amplified its inherent tensions and added new meanings to its use.

It is not always clear whether any given instance of Victorian heraldry reflects a solemn return to a sometimes invented tradition, a playful romantic yearning for the Medieval past, mere adherence to fashion, or all of these. Those Victorians who could, put heraldry on everything from tobacco tins through to coach doors. We see revived or at least reinvigorated traditions such as the funerary practice of displaying the arms of the deceased on a “hatchment” to be hung first outside their late home, and then, after a year, within the church. We also see Victorian technology enabling new traditions, most markedly pre-printed headed note-paper with “heraldic crests”.

This fashionable prominence had the effect of diluting and undermining its subject: First, adherents of the Gothic Revival were more serious about romanticism than scholarship. This was the imaginative world of Walpole and Walter Scott, which reached its apogee in the Eglinton Tournament, a massive and expensive recreated Medieval tournament prefiguring modern Renaissance Fairs. Where scholarship was claimed, this was often only for romantic effect. Most arms coming out of the Gothic Revival often stretched the strict rules of “blazon” (composition) in favour of flamboyance, especially regarding supporters and crests. It also tended towards “realism”, with the various devices depicted artistically rather than as symbols. In this playful world, Heraldry became a mere prop and ultimately a cliché, so much so that a reverse snobbery came into effect, with heraldic crests supplanting full coats-of-arms for those with who aspired to more refined tastes.

However, by encouraging publications on the subject, the Gothic Revival also underwrote new heraldic scholarship. By the 1850s, this resulted in a reaction against the perceived excesses of the recent past and a return to simpler, albeit stiffer, designs reflecting earlier traditions. Illustration: Two coats-of-arms from different generations of the same family, showing how styles reverted to older, simpler forms.

Second, heraldry became a too-obvious and too-easily adopted status symbol. The running conflict between the heraldic haves and have-nots is an ancient one. The established “armigerous” families kept their exclusivity through the Colleges of Heralds, established in the Middle Ages. Heralds were slow to grant arms, demanded onerous bone fides, and charged stiff fees. Consequently, the newly rich and the ambitious often jumped the gun, inventing or assuming arms that were not theirs to display. For example, the Heathcoat-Armorys of Knightshayes Court initially adopted the seventeenth-century arms of Armour of Devon, to whom they were not related. They only acquired legitimate arms in 1874, when John Heathcoat-Armory became a baronet. (Woodcock and Robinson, Heraldry in National Trust Houses, 108)

This approach to heraldry was containable in an Early Modern Britain, which had a population of around 5 million, but less so in industrial Britain with a more socially mobile population of around 30 million, some scattered about the Empire, and most with access to inexpensive printing bureaux. Thus, the nouveau riche continued to acquire coats-of-arms through official channels. One example is the industrialist and arms magnate, William Armstrong, who became Baron Armstrong of Cragside in 1887, so receiving a grant of arms (Woodcock and Robinson, Heraldry in National Trust Houses, 76). However, anybody with even a middling income could elide the expensive and ponderous Heralds and simply “discover” a family coat-of-arms, or perhaps an increasingly fashionable understated “family crest”, with the help of a stationer. They would often be aided by glance through one of the many heraldic manuals in print to thanks to the Gothic Revival. If challenged, they could point to their payment of the Armorial Bearings Duty, instituted to help finance the Napoleonic Wars and not ended until after the Second World War. Effectively a vanity tax, this duty was chargeable on armorial bearings “whether registered in the college of arms or not”, and thus gave a quasi-official stamp of approval to arms that had not been properly granted.

Small wonder then that by the middle of the period if not before, manners and morality, rather than heraldry, were seen as the markers for a gentleman (Gilmore, 4). The Gothic Revival crumbled, like much else, during the Great War. The College of Arms still operates and still grants arms to individuals. However, the public display of heraldry is now relegated to moments of high public ritual, and to historical re-enactments.

Select Bibliography

Gilmour, Robin. The Idea of the Gentleman in the Victorian Novel. Routledge, 2016.

Woodcock and Robinson. The Oxford Guide to Heraldry. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988.

Woodcock and Robinson. Heraldry in National Trust Houses. National Trust, 2000.

Last modified 10 August 2017