The Raj Bhavan (Government House), Kolkata, India. Architect: Charles Wyatt (1758-1819), one of the Wyatt architectural dynasty so prominent in nineteenth-century England. 1799 (first used for entertaining in May 1802, formally opened in January 1803). Stuccoed brick, with the plaster originally painted yellow (cf parts of the later High Court). Situated majestically in spacious grounds overlooking the city's maidan, Kolkata's unusually vast sweep of open parkland, this was a keynote building if ever there was one. Colour photographs and commentary by Jacqueline Banerjee. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL or credit the Victorian Web in a print one.]

The Raj Bhavan was built at the behest of the Marquess of Wellesley (1760-1842), the future Duke of Wellington's elder brother. He had come to India in 1798 as Governor-General of Bengal for the East India Company., and had found the present rented accommodation unsuitable. The company's Civil Architect at that time was a colourful Italian, Edward Tiretta; but on this occasion young Lieutenant Wyatt's plans won the day. As seen here, the main front with its elegant classical portico is approached by a grand set of stone steps. The central part then curves forward into sturdy three-storey pavilions at each end. Two further matching pavilions curve out behind from the same central block.

Photograph of the Raj Bhavan used for the frontispiece of the Rev. R. K. Firminger's Thacker's Guide to Calcutta in 1906 (sky mottling digitally removed). The trees had not yet grown.

Photograph of the rear or southern elevation, with the dome added later on (Massey, frontispiece, again, with the sky slightly modified).

The building is a notable variation on Robert Adam's fine Kedleston Hall in Derbyshire. Wyatt's architect uncle, Samuel Wyatt, had been involved with that, and it was natural that his nephew should have been inspired by it. But the differences are perhaps as important as the similarities: the English building has only two wings, not four, and Wyatt has taken account of the different climate and added cool, spacious verandahs and another portico on the garden side, this one semi-circular. In 1814 the rear portico was crowned with a dome, to add to its effect (see Davies 65). The result not only set the tone for colonial Calcutta — a "city of palaces" — but was the first of the grand colonial palaces of the Raj.

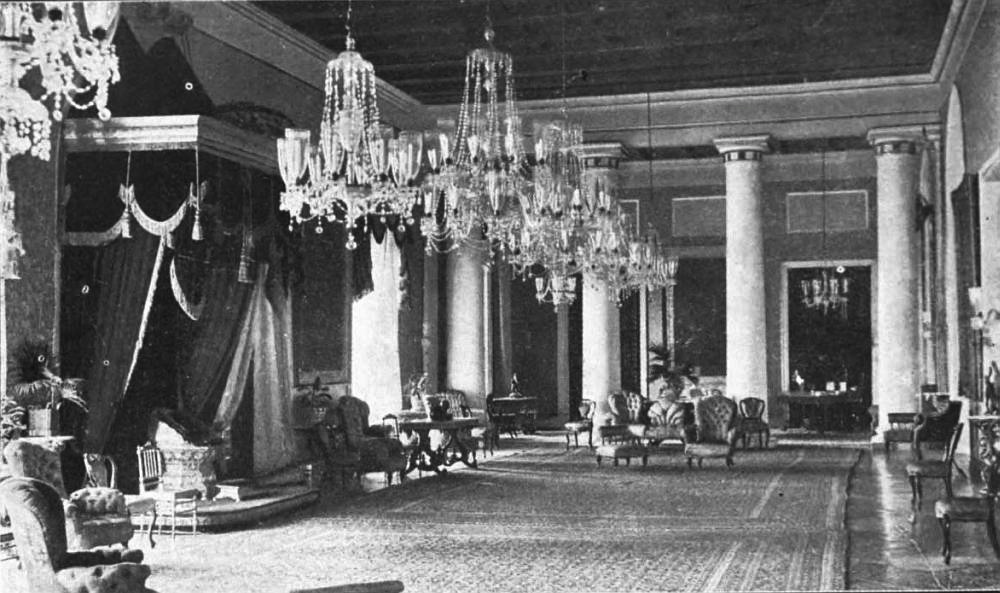

Left: Photograph of the ballroom in about 1918 (Massey, facing p.44). Right: Photograph of the Throne Room, from the same time (Massey, facing p. 45).

The Rev. Firminger's early account gives us some more details about the Raj Bhavan's setting and the splendid interior:

The House stands in a garden of about six acres..... before it there is an interesting cannon shaped as a dragon, placed here by Lord Ellenborough as a trophy of the Chinese war. .... The length of the building lies between east and west — to secure the south breeze on which Calcutta folk so much rely as the "cold season" becomes humid. The Royal arms in the north pediment and on the north and south sides, as well as the classical urns were all added by Lord Curzon, who also had changed the dirty yellow of the exterior of the house for pure white. The public or ceremonial rooms occupy the main portion of the building: the private accommodation for the Viceroy's family and staff are in the wings. The ordinary entrance is from a passage beneath the ceremonial stairway.

On the first floor to the left on entering by the external stairs, is the Breakfast Room, looking out over Government Place. East of this the Council Room, the Throne Room, where we see the throne of Tippu Sultan, and the Dining Room, with its chunam columns, china marble floor, and busts of the Caesars, are on this floor.

On the second floor is the great ball-room, the chandeliers, like the busts of the Caesars below, are said to have been captured from a French ship during one of the wars, but it is more probable that they formed part of the spoil of Chandernagore once housed in the long since vanished Court House.... (48).

One of the four great gateways at the approaches to the building, crowned with suitably majestic lions.

Not everything here was praised. The absence of a central staircase was particularly criticised (see Davies 65). To modern eyes, too, there is a distinct and uncomfortable feeling throughout of the British lording it over the subject race, something very noticeable in the four huge gateways to the grounds, with their sculptured lions. But that of course was exactly the impression originally intended. As Jan Morris has said, "it was a deliberate declaration of power and success" (67).

References

Davies, Philip. Splendours of the Raj: British Architecture in India, 1660-1947. London: Penguin, 1987. Print.

Firminger, Rev. W. K. Thacker's Guide to Calcutta. Calcutta: Thacker, Spink & Co., 1906. Internet Archive. Web. 12 February 2013.

Massey, Montague. Recollections of Calcutta for over Half a Century. Calcutta: Thacker, Spink & Co., 1918. Open Library. Web. 12 February 2013.

Morris, Jan, with Simon Winchester. Stones of Empire: The Buildings of the Raj. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005. Print.

Last modified 12 February 2013