The small parish church in Kilmartin, a Scottish village of less than 100 people, contains three memorial tablets to men of the Campbell family that have much to tell us about the British Empire and its armies. I was immediately struck by the fact that these men from a single family not only ran and often fought for the widest reaches of the empire but also that the family placed memorials in this remote little church.

Left: Kilmartin Paris Church. Joseph Gordon Davis. 1834-35. Kilmartin, Argyll and Bute, Scotland. Middle: Church interior looking towards communion table. Right: The church’s surroundings. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

A link between the British Empire and the rough-hewn early capitalism of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century — capitalism with few governmental protections for investors or depositors in banks — appears in the reason why Neil Campbell, the eldest person memorialized, lived and died in India: the failure of a local bank. As the inscribed marble explains, “in 1786 he went to the East Indies, hoping by this honourable exertion to retrieve his paternal inheritance from debt incurred by the failure of the Ayr bank, and by liberal pecuniary engagements for others.” This Campbell, who fought in “the American War,” ended up in India where he held the positions of “High Sheriff, Commissary of Musters to the King’s army and A. D. Camp to the Nabob of Arcot.” Whereas the father fought in North America, the Carribean, and India, his eldest son, James, “served in the East Indies at the siege of Ponchberry in 1793, at the capture of the Cape of Good Hope in 1795, and in Holland in 1799 where he fell in battle.”

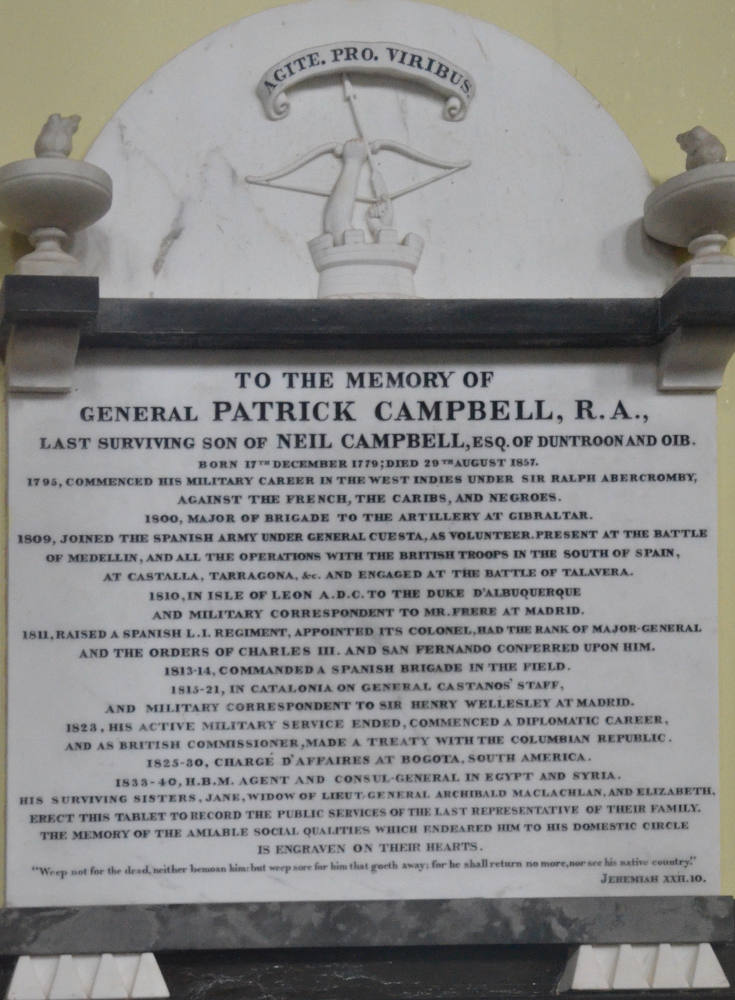

Left: Memorial for Neil Campbell (1736-1799) and James Campbell (d.1799). Middle: Memorial for Sir Neil Campbell (1776-1835). Right: Memorial for General Patrick Campbell, R.A.. [Click on images both to enlarge them and for transcriptions of the memorials.]

The Campbell son named after his father, Sir Neil Campbell, “C.B. Colonel of the Royal African Corps, [Governor?] Commander in chief of Sierra Leone and its dependencies,” served “in the West Indies, Spain, Portugal, Germany, the Netherlands, & France, [and] at length fell a sacrifice to the baneful climate of Africa, on 14th May, 1827.” General Patrick Campbell had a particularly interesting career, which began in the Caribbean, where he fought “against the French, the Caribs, and Negroes,” after which he moved back across the Atlantic, first to Gibraltar and then to Spain, where he simultaneously served as an officer in the Spanish army while acting as a “military correspondent” for important British figures back in London. Retiring from the army, he “commenced a diplomatic career” in South America, Egypt, and Syria. I found surprising, not his moves around the world in the service of the Queen, but the fact that he served in foreign armies without harming his military or diplomatic careers. Perhaps serving with the armies of an allied country prepared his diplomatic career. His years in Spain certainly helped his diplomatic efforts, which included negotiating a treaty with Columbia. He ended his career with seven years as “Agent and Consul-General in Egypt and Syria.” Clearly, serving the empire did not necessarily require a specialized knowledge of any particular country or region.

One point to take away from Kilmartin’s parish church: men from tiny, remote Scottish towns made their mark — and their living — thousands of miles away from home amid vastly different climates and cultures. Nonetheless, wherever their bones were interred, they and their families felt the need for these biographical memorials in this tiny church in a tiny village.

Related material including reviews of recent books

- The British Empire: An Introduction

- Fear of losing markets and the 'new imperialism' of the 1880s

- The Industrial Revolution, Textiles, and Empire

- Ambivalence, Economy, and Empire in Victorian Britain

- Disraeli's Imperial Policies

- Why did the British Empire expand so rapidly between 1870 and 1900?

- The Role of the Victorian Army

- Imperial and Postimperial Rhetorics of Benevolence. A Review of Helen Gilbert and Chris Tiffin's Burden or Benefit?

- Preparing Children for Empire: “ Introduction,” Megan E. Norcia's X Marks the Spot: Women Writers Map the Empire for British Children

- [Review of] by Stephanie Barczewski’s Heroic Failure and the British

Last modified 13 September 2016