The 'Earl of Abergavenny' East Indiaman, off Southsea. 1801. Oil on canvas, 86.5 x 152 cm. Courtesy of the British Library. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

In retrospect it seems curious that it took so long for the British to identify quicker routes to India. From the earliest times of the East India Company the preferred route was by sailing ship, usually the armed merchant vessels known as East Indiamen, from the Thames to Bombay (modern Mumbai) with an alternative route to Madras (Chennai) and Calcutta (Kolkata). These journeys could take anything from 3 to 5 months each way depending on wind and weather. Furthermore some ships did not make it; sinking in storms or due to navigational errors.

Some of these sinkings became big international stories; similar to some of the big airline disasters of modern times. For example the loss of the Abergavenny in 1805 (captained by John Wordsworth, the brother of the famous poet) saw 260 passengers and crew drowned in Weymouth Bay. Another epic Indiaman disaster was the Grosvenor which ran ashore in modern South Africa in 1782. Of 123 survivors of the wreck only 18 succeeded in reaching the safety of Cape Town. And in 1808 three East Indiamen sank in the great storm of November 1808; the Glory, the Experiment and the Lord Nelson.

Cairo from Richardson’s book on the overland route to India.

As early as 1798 the Company experimented with sending mail via Egypt by a regular ship known as “the Suez packet”. This ship would land at Suez and the mail would be taken overland to Cairo and then down one branch of the Nile to Rosetta, thence to Alexandria. It was not a popular route. The Red Sea was fraught with dangers and the trip between Suez and Cairo was beset with hostile Bedouin tribesmen. The route down the Nile was also dangerous with shoals and large numbers of crocodiles.

Three Rival Routes from England to India

1. Ships Powered by steam engines instead of wind and sails: In the late 1820s three rival ideas began to gain currency for shortening the route to India. The first was the steamship to replace the old wooden Indiamen. In 1825 the SS Enterprise made the first passage to Calcutta but took 13 weeks. It was a revolutionary moment in shipping history but clearly did not provide the whole answer to the problem.

Left: The title-page from Chesney’s Narrative of the Euphrates Expedition (1868). Middle: Plan of the Position of the Tigris and Euphrates Steam vessels on the 21st of May 1836. Left: Captain Francis Rawdon Chesney

Left: Capt. Chesney’s Raft, in 1836 from an 1868 lithograph by A. Picken. Right: Images of the ships’s boilers the expedition had to transport overland.

2. The Euphrates Route: The second idea was the Euphrates route. Captain Francis Rawdon Chesney was the main adherent of this way to India. The theory was that a ship would sail from Bombay to Basrah in the Persian Gulf where passengers and cargo would transfer to a river boat all the way up the Euphrates via Najaf, Karbala, Ramadi, and Deir ez Zor to Bircelik whence there would be a short overland route via Aleppo to the Mediterranean coast at Alexandretta (modern Iskenderum) or Suedia (Samandag). Chesney tried out the route in 1835 but the expedition was only a partial success and the idea remained dormant for many years.

Left: The loss of the Tigris as the Euphrates survives a storm drawn by Col. Estcourt, Right: The wagon loaded with parts of the steam engine crossing a river drawn by Lieutenant Fitz Jones and lithographed by H. Warren.

As late as 1868 (the year before the Suez Canal opened) Chesney was still championing the route in his Narrative of the Euphrates Expedition.

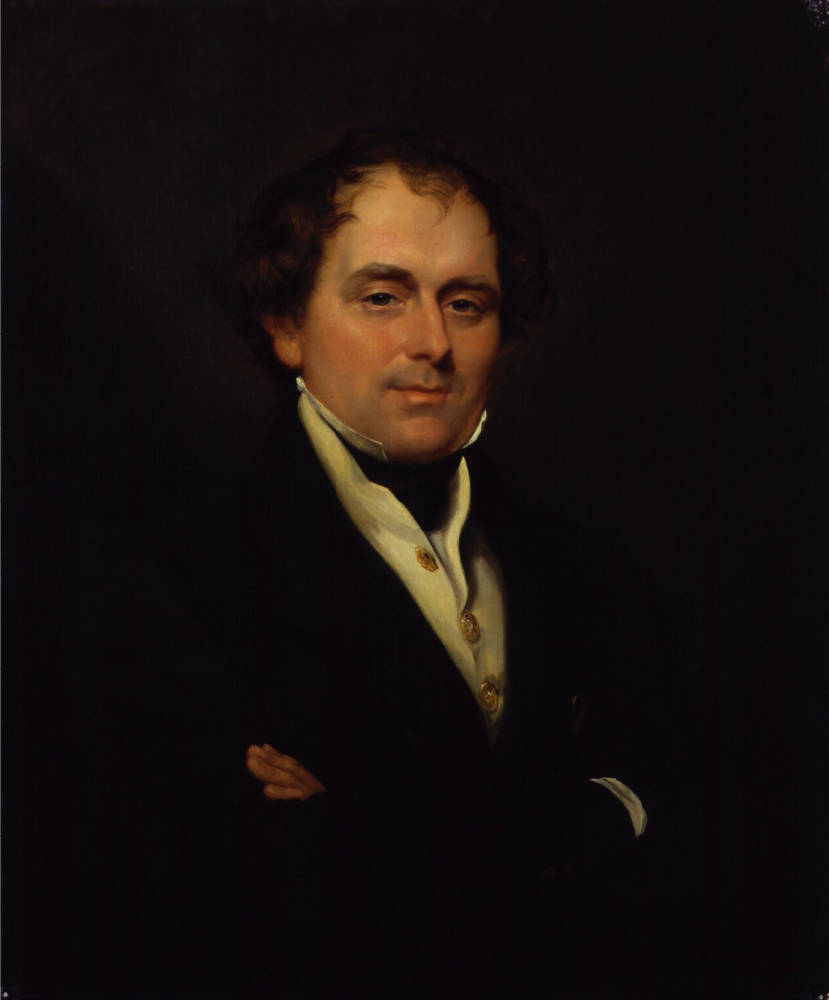

Thomas Waghorn. Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, London NPG 974.

3. The Overland Route: The third option had more success. A young naval officer Thomas Waghorn argued for the route across Egypt, very similar to that used for mail in 1798. Waghorn has always been a controversial figure. He was from a humble background and was always accused of being a self-publicist. However he had a remarkable determination, a quality he shared with both Chesney and a third great figure; the Frenchman Ferdinand de Lesseps, who eventually built the Suez Canal.

In 1830 some dispatches sent from India aboard the new steamer Sir Hugh Lindsay reached London in just 33 days. Waghorn hatched a plan for a regular service with steamers operating from Trieste to Alexandria and another service from Suez to Bombay. This left the major problem of how to get passengers and cargo safely from Alexandria to Suez. The first part involved a journey from Alexandria to the Rosetta branch of the Nile. For this the Mahmoudieh canal was used. The 45 mile canal had been built by the Egyptians in 1817 to bring fresh water to Alexandria. Now horses were used to haul long barges of passengers along the narrow canal to the town on Mahmoudieh where they transferred to Nile steamers for the voyage upstream to Boulac on the outskirts of Cairo. For the more hazardous trip across the desert to Suez 8 secure waypoints were prepared complete with towers to protect the convoys. Between 1831 and 1834 Waghorn’s customers averaged 47 days from Bombay to London and vice versa.

In 1835 the Sir Hugh Lindsay began a regular service from Bombay to Suez and in 1840 the contract for the service was awarded to P & O (the Peninsular and Orient Line) which later became synonymous with the passage to India and gave us the word “posh” (port side out starboard home). Further improvements came with the railways. The route from England down the Rhine to Trieste was replaced by the rail service from London to Marseilles. Also by improving the road from Cairo to Suez Waghorn cut the route across Egypt to 6 days

The Mahmoudieh Canal today. Photograph by the author.

De Cosson relates an early transit using Waghorn’s route by the traveller, Leopold von Orlich in 1842. At Alexandria he embarked in a boat on the Mahmoudieh Canal, which he describes as being fifty paces broad and about six feet deep. The boat was drawn by four horses as far as Atfa on the Nile where the Lotus, a steamer, received them and conveyed them to Cairo. From Cairo von Orlich was taken over Waghorn's road to Suez in a two-wheeled cart with a linen awning and drawn by four horses. Von Orlich complained of the heat in July under the linen awning and was glad to get on board the Berenice in which he sailed for India.

The writer W.M. Thackeray described a similar trip in 1844. In Cairo he met Waghorn and wrote; “The bells are ringing prodigiously; and Lieutenant Waghorn is bouncing in and out of the courtyard full of business. He only left Bombay yesterday morning, was seen in the Red Sea on Tuesday, is engaged to dinner this afternoon in the Regent’s Park, and (as it is about two minutes since I saw him in the courtyard) I make no doubt he is by this time at Alexandria, or at Malta, say, perhaps, at both. If any man can be at two places at once (which I don’t believe or deny) Waghorn is he.”

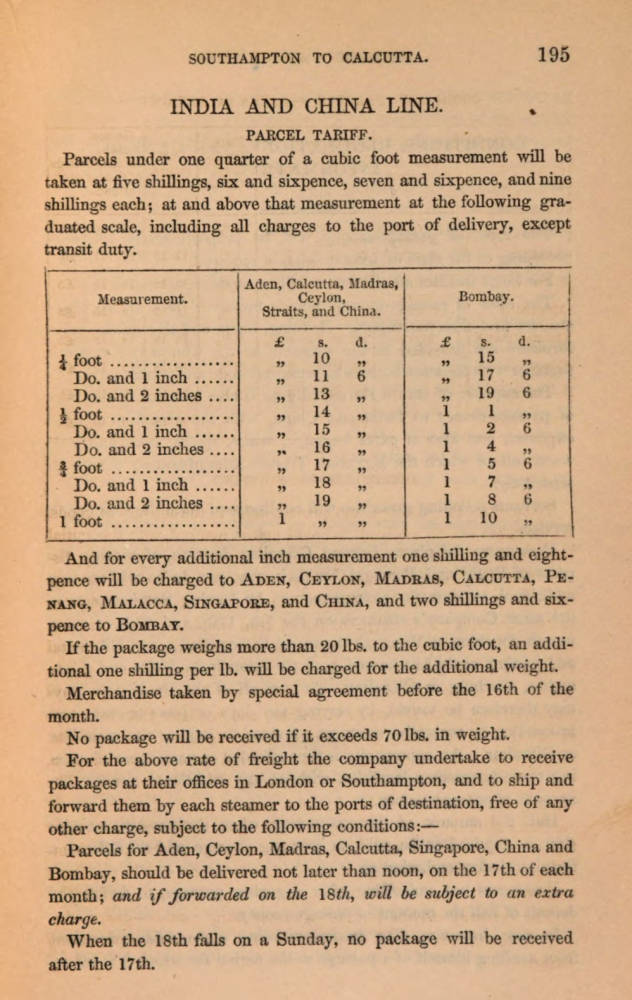

The title-page and two from Richardson’s The Anglo-Indian Passage (1849) with pages showing schedules for the overland route and costs of shipping parcels via the India and China Line.

David Lester Richardson devoted a whole book to the land route to and from India before the Suez Canal transformed the experience. His own father had drowned in the Lord Nelson in 1808 and so he harboured no nostalgia for old era of the East Indiamen. His aunt the poet Eliza Richardson who endured several gruelling voyages to India later wrote;

The experienced sailor long inured to danger

Rides over death, nor heeds his stern array;

Life’s youthful voyager, to fear a stranger,

Through paths of equal peril journeys gay.....

And since I know how fatally alluring

May I ne’er again tempt thy smiling wave,

But with firm mind each passing change enduring

Look to a haven, that’s beyond the grave”

By the time David reached Alexandria a steam tug had replaced the horses pulling the barges on the Mahmoudieh canal. The whole experience was becoming more comfortable as good hotels opened in Cairo and Alexandria. In 1854 the railway line between Alexandria and the Nile was opened and extended to Cairo in 1856. So the Mahmoudieh canal’s period of fame was short-lived; from 1831 to 1854. Since then it has fallen into disrepair and my photograph shows the best section still remaining. Much of the rest is little more than a muddy ditch full of debris.

A table from Richardson’s Anglo-Indian Passage (1849) showing “the length of passage, under ordinary circumstances, from Southampton to several ports.”

Related Material

Further reading

Chesney, Francis Rawdon. Narrative of the Euphrates Expedition. London; Longman’s Green, 1868. Hathi Trust Digital Library online version of a copy in the University of Michigan Library. Web. 30 July 2020.

De Cosson, A.F. “The old overland route to India.” Calcutta; Bengal Past and Present: Journal of the Calcutta Historical Society. (January to June 1915): 211-21. Internet Archive version of a copy in the Public Library of India. Web. 30 July 2020.

Hayter, Andrea. The wreck of the Abergavenny. London; Macmillan, 2002.

Richardson, David Lester. The Anglo-Indian Passage Homeward and Outward. London; Madden and Malcolm, 1849. Hathi Trust Digital Library online version of a copy in the Harvard University Library. Web. 29 July 2020.

Richardson, Eliza. Reflections at Sea. From Poems. Edinburgh; Cadell, 1828.

Taylor, Stephen. The Caliban Shore. London; Faber and Faber, 2004.

Willasey-Wilsey, Tim. “Of intelligence, an assassination, East Indiamen and the Great Hurricane of 1808.” Victorian Web, 2014.

Last modified 30 July 2020